From Clay to Code: The First Scripts and Why They Mattered

Why Remembering Got Hard

Before writing, memory relied on muscle alone. People tracked debts, seasons, and stories in their heads, hoping nothing slipped. Oral recall was strong, yet errors crept in.

Imagine a crowded Mesopotamian market. A merchant had to recall every deal and promise. Trust stretched thin as villages grew. One forgotten detail could spark trouble.

Farming expanded populations and supply chains. More people meant more complexity. Rulers, priests, and traders needed a backup beyond fallible minds.

External memory—putting thoughts into objects—solved that. Showing ideas, not just telling them, unlocked larger societies and stable trade.

Making Marks: Cuneiform, Hieroglyphs, and the First Alphabets

Around 3200 BCE, accountants in Mesopotamia pressed wedge shapes into clay. These marks formed cuneiform and first counted goods like sheep or grain.

Cuneiform started as one sign per object—a logographic system. Great for ledgers, poor for poetry.

Scribes soon borrowed signs for their sounds. Symbols shifted from meaning to phonetics, adding flexibility.

In Egypt, dazzling hieroglyphs mixed ideas and sounds. One carved sign could be a word, an object, or simply a sound—each word a puzzle.

By 1200 BCE, the Phoenicians trimmed writing to a few marks, each for one sound. This alphabetic leap made literacy easier. Greek and Latin scripts—and today’s letters—descend from that breakthrough.

Papyrus, Parchment, and the Power of Materials

Sumerians used clay—cheap, durable, yet heavy. Short messages suited the weight. Archaeologists still read those tablets today.

Egyptians crafted papyrus, thin and rollable. It lightened communication but wilted in damp climates. Portability let more voices write and travel.

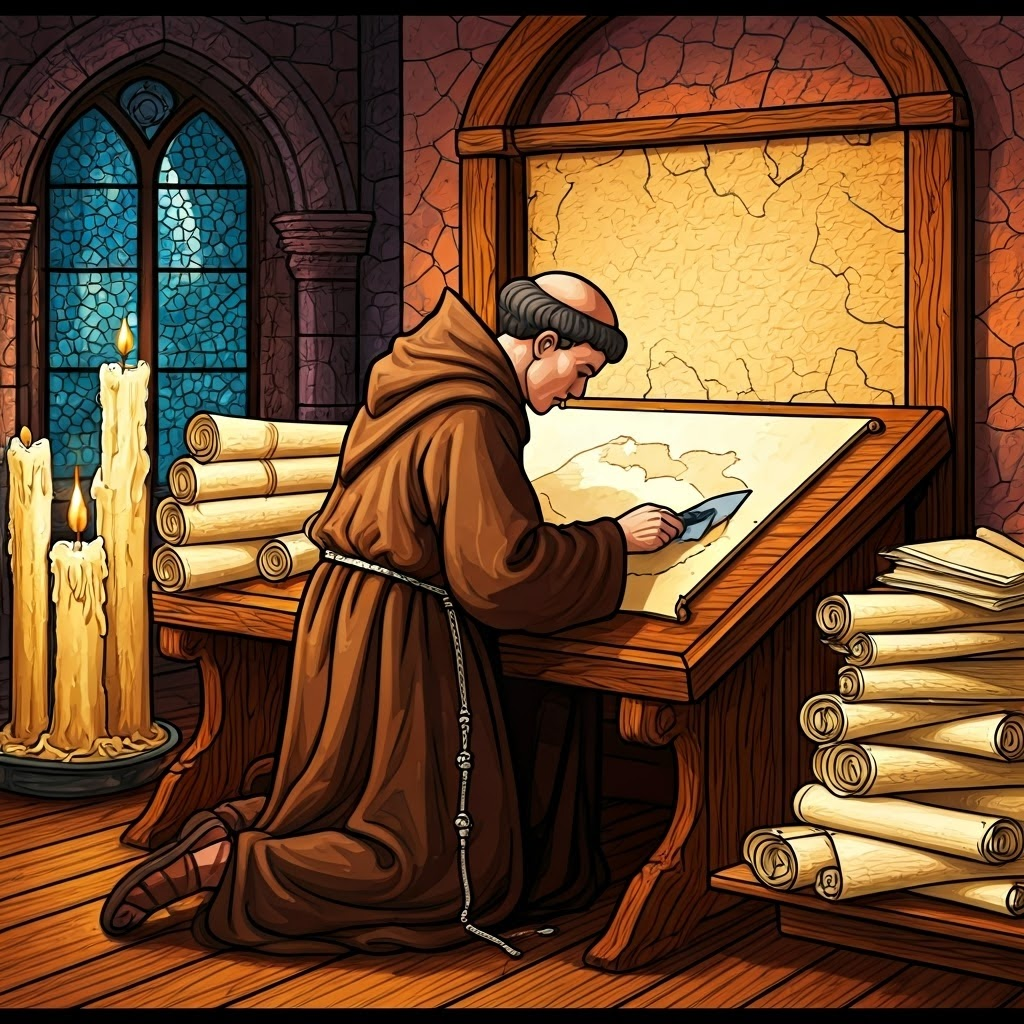

Cooler regions turned to parchment and vellum—animal skins scraped thin. They were sturdy and reusable. Medieval monks preserved knowledge on these pages for centuries.

The material shapes the message. Heavy clay favors brief records. Fragile papyrus demands care. Cheaper, lighter, durable surfaces widen who can write and what survives.

The Mix of Script and Surface

Clay spawned contracts and lists. Portable media carried stories, letters, and laws farther—like a sticky note versus a global email.

The Beginning of Collective Memory

Scripts, sounds, and mobile surfaces built the first collective memory. Writing layered atop speech, letting distant cities coordinate and ordinary people reach beyond local lore.

Walter Ong noted that external storage creates a “second mind”—an archive outside the body. That archive powers science, government, and everyday gossip.

Your phone’s alphabet, notes, and receipts echo those early clay tablets and papyrus scrolls. They prove that memory can live outside your mind.