How We Find New Worlds: The Art and Science of Discovery

Spotting Shadows: The Transit Method

Imagine holding a flashlight in a dark room while a marble drifts across the beam. Each pass makes the light dip for a moment. Astronomers watch for the same small drop in a star’s brightness to reveal an orbiting planet — this is the transit method.

Even a giant planet blocks only a sliver of starlight. Jupiter would dim a Sun-like star by about 1%. An Earth-sized world hides less than 0.01%. Sensitive telescopes spot that faint change, then track how often it repeats.

Kepler fixated on one small sky patch for years, measuring over 150,000 stars. When a dip repeated on schedule, it flagged a likely planet. TESS now sweeps almost the entire sky, trading depth for breadth and catching transits in many directions.

The method favors big planets orbiting close to small stars, because their shadows are deeper and occur often. Early finds were mostly “hot Jupiters.” Improved optics now reveal smaller, cooler worlds — some just larger than Earth.

Alignment matters. If a planet’s orbit tilts away from our line of sight, its shadow never crosses the star from our view. Still, transit data provide size, orbital period, and hints of an atmosphere when combined with other observations.

Wobbling Stars: The Radial Velocity Trick

Picture two dancers spinning together. The lighter partner sweeps wide circles, yet the heavier one shifts slightly in response. A star and planet perform the same dance around a shared center, causing the star to wobble.

Astronomers detect that wobble through the Doppler effect. When the star moves toward us, its light shifts bluer; when it recedes, redder. Instruments now measure changes of just a few meters per second — about a slow jog.

The first planet around a Sun-like star, 51 Pegasi b, surfaced in 1995 via radial velocity. This technique excels at spotting hefty worlds in tight orbits and works even when no transit occurs. Modern spectrographs can sense motions of only a few centimeters per second, opening the hunt for lighter planets.

Stellar spots and flares can mimic a wobble, and the method alone yields only a minimum mass. Pairing radial velocity with transits solves that: size plus mass gives density, hinting at a planet’s composition.

Catching a Glimpse: Direct Imaging

Finding a planet next to its star is like spotting a firefly by a floodlight. Direct imaging blocks or subtracts the star’s glare with tools such as a coronagraph, letting faint planetary light emerge.

This strategy prefers large, young, and distant planets that shine brightly in infrared. Even then, images often shrink to a pixel or two, but that pixel reveals temperature, atmosphere, and sometimes moons or rings.

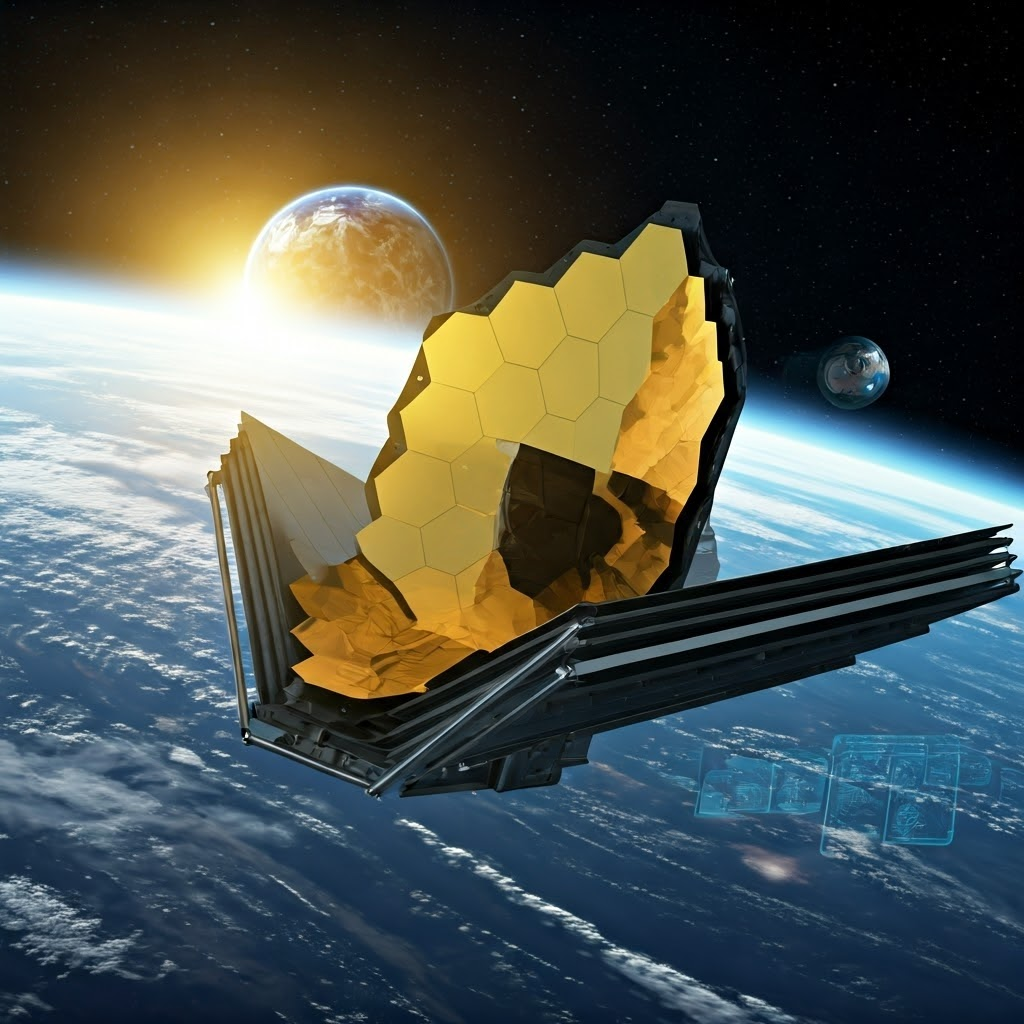

The first direct shots, like the HR 8799 system in 2008, came from ground giants such as Keck. New observatories — including the James Webb Space Telescope — feature sharper optics and superior glare suppression, promising many more pictures of distant worlds.

Teamwork Makes Discovery Work

No single approach sees everything. Some planets never transit, some stars wobble unpredictably, and direct images remain rare. Combining methods fills the gaps and confirms finds.

Kepler and TESS proved planets abound. Radial velocity uncovered eccentric giants. Imaging now lets us inspect atmospheres directly. Each new world shows how varied planetary systems can be and reminds us that exploration blends careful measurement with a spark of creativity.