From Waterwheels to Wonder: The World Before Steam

Before steam engines, people relied on muscle, wind, and water to move heavy loads. Work in fields and workshops followed nature’s rhythms. Power was slow, local, and unreliable. Farmers and craftsmen timed every task around daylight, seasons, and the strength of humans or animals.

Muscle, Wind, and Water: The Old Ways

Daily labor leaned on animal strength. Long hours of plowing, lifting, or grinding wore people down. Extra horses helped, yet progress stayed slow, and the animals needed constant care.

Where streams flowed, waterwheels offered steady power. Mills in places like Abbeydale ran hammers, saws, and grindstones for years. Droughts or distance from water, though, could stop everything.

Windmills delivered variable power. They pumped water and ground grain across the Netherlands and eastern England. When the breeze died, work halted, and these tall structures could never move to better spots.

Town workshops felt the weight of manual effort. Apprentices pumped bellows for hours, and crews walked tread wheels or turned cranks. William Blake’s “dark Satanic mills” captured the drudgery of this era.

The Mining Problem: Water Everywhere

Deep coal seams brought flooding. Britain’s miners used buckets, chain pumps, and drainage tunnels, yet water still poured in as shafts sank lower.

Buckets and rag pumps moved little water. Gravity-driven adits helped only on shallow slopes. Deeper levels stayed soaked.

Muscle, wind, and water simply failed underground. Mines closed, investors panicked, and fortunes vanished as water kept rising.

Newcomen’s Big Idea

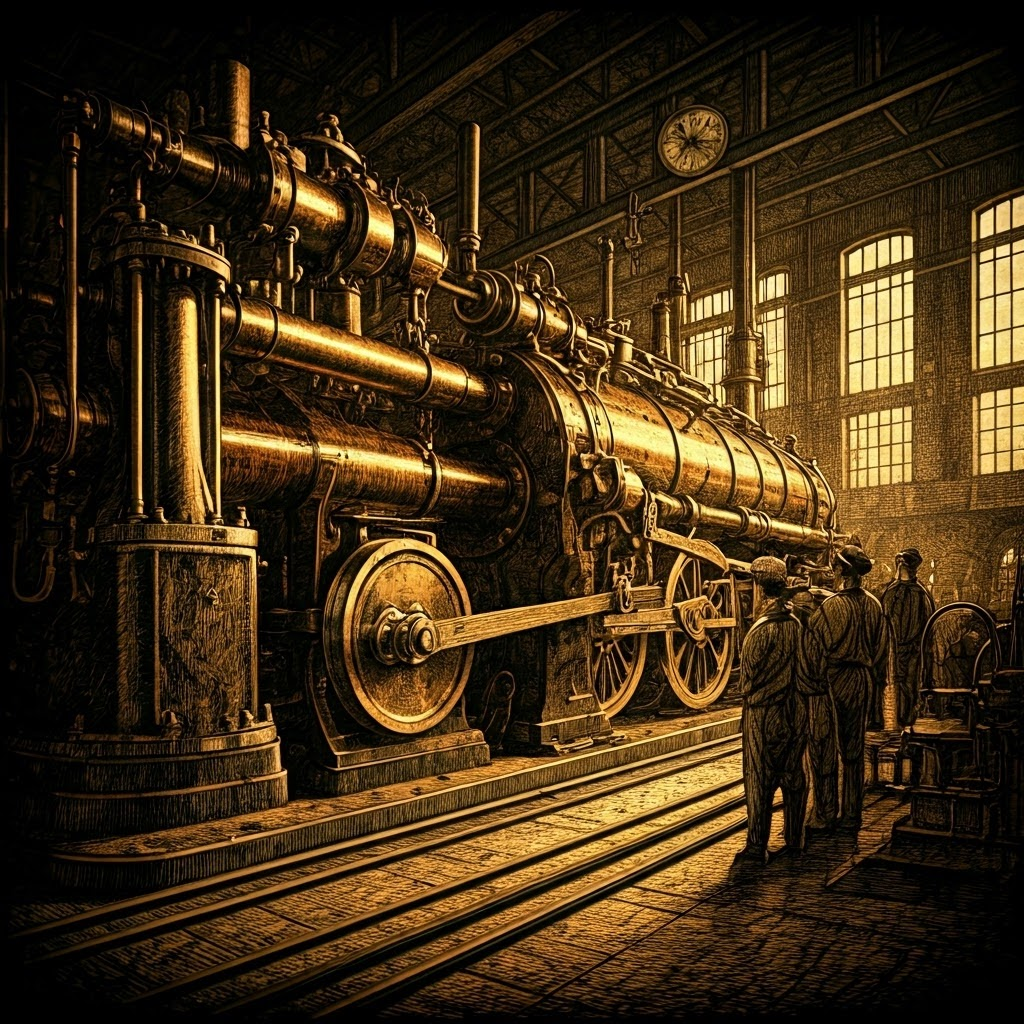

Thomas Newcomen, a Devon blacksmith, unveiled a steam engine in 1712. Slow and noisy, its rocking beam powered only a pump—but that pump ran day and night.

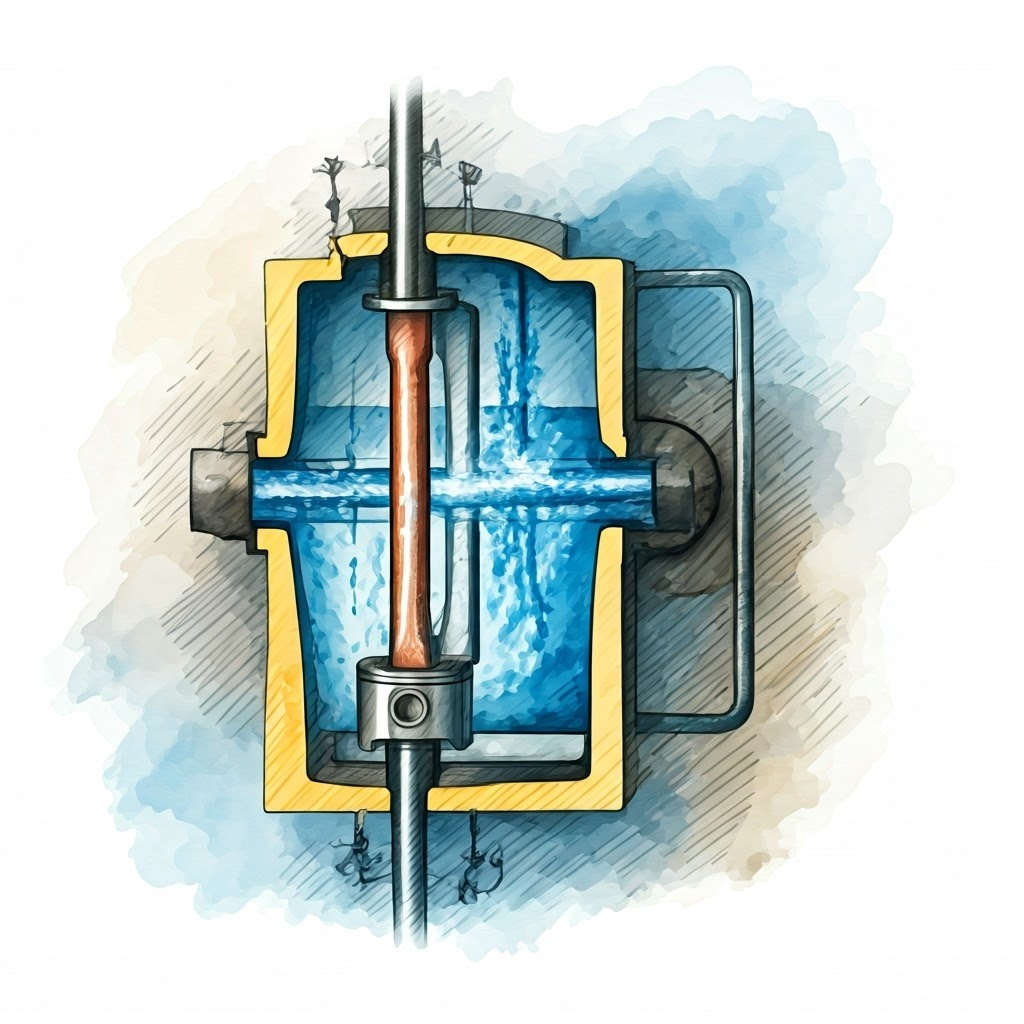

Steam pushed the piston up. Cold water cooled the cylinder, creating a vacuum. Air pressure drove the piston down. The beam’s up-and-down motion pulled water from flooded shafts, replacing teams of horses.

Engines spread where flooding hurt most—Cornish tin mines and Midlands coal pits. Fewer than a hundred engines saved countless shafts from closure.

The design burned plenty of coal, yet on-site fuel kept costs bearable. For desperate mine owners, the engine turned disaster into profit.

Newcomen’s machine felt almost magical. By freeing industry from nature’s limits, it laid the groundwork for bigger leaps in steam power and, ultimately, the Industrial Revolution.