Lighting the Spark: The First Demands for a Voice

A World Without Women’s Votes

Living before women could vote feels like living with half your voice missing. Imagine paying taxes, obeying laws, and raising children, but when it’s time to decide who leads your city or writes your country’s rules, you stand quietly aside. In the 1800s in the US, UK, and much of the world, this was simply what people called “the natural order.” Women’s legal status was often similar to that of a child. If you married, your wages, your property, even your children could be legally controlled by your husband. University doors were mostly closed. Jury duty? Not for you. Control over your own life? Only as much as your father, brother, or husband allowed.

Just to own property, sign a contract, or keep your own earnings was a battle. Picture a working woman in Manchester in 1840: she could sew shirts for twelve hours, but every penny legally belonged to her husband or father. Across the Atlantic, a woman in New York who inherited farmland would see it handed over to her spouse. Even women like Harriet Taylor Mill or Mary Wollstonecraft—whose writings poked at the unfairness—were often ignored or dismissed as “unwomanly.” Voting, the most basic sign of citizenship, was treated as a man’s business. But as cities grew, factories roared, and new ideas spread, more women began to quietly, then loudly, ask: “Why not us?” The world was changing, and women’s exclusion became harder to justify. This spark, once lit, would be very hard to put out.

Just to own property, sign a contract, or keep your own earnings was a battle. Picture a working woman in Manchester in 1840: she could sew shirts for twelve hours, but every penny legally belonged to her husband or father. Across the Atlantic, a woman in New York who inherited farmland would see it handed over to her spouse. Even women like Harriet Taylor Mill or Mary Wollstonecraft—whose writings poked at the unfairness—were often ignored or dismissed as “unwomanly.” Voting, the most basic sign of citizenship, was treated as a man’s business. But as cities grew, factories roared, and new ideas spread, more women began to quietly, then loudly, ask: “Why not us?” The world was changing, and women’s exclusion became harder to justify. This spark, once lit, would be very hard to put out.

Seneca Falls and the First Declarations

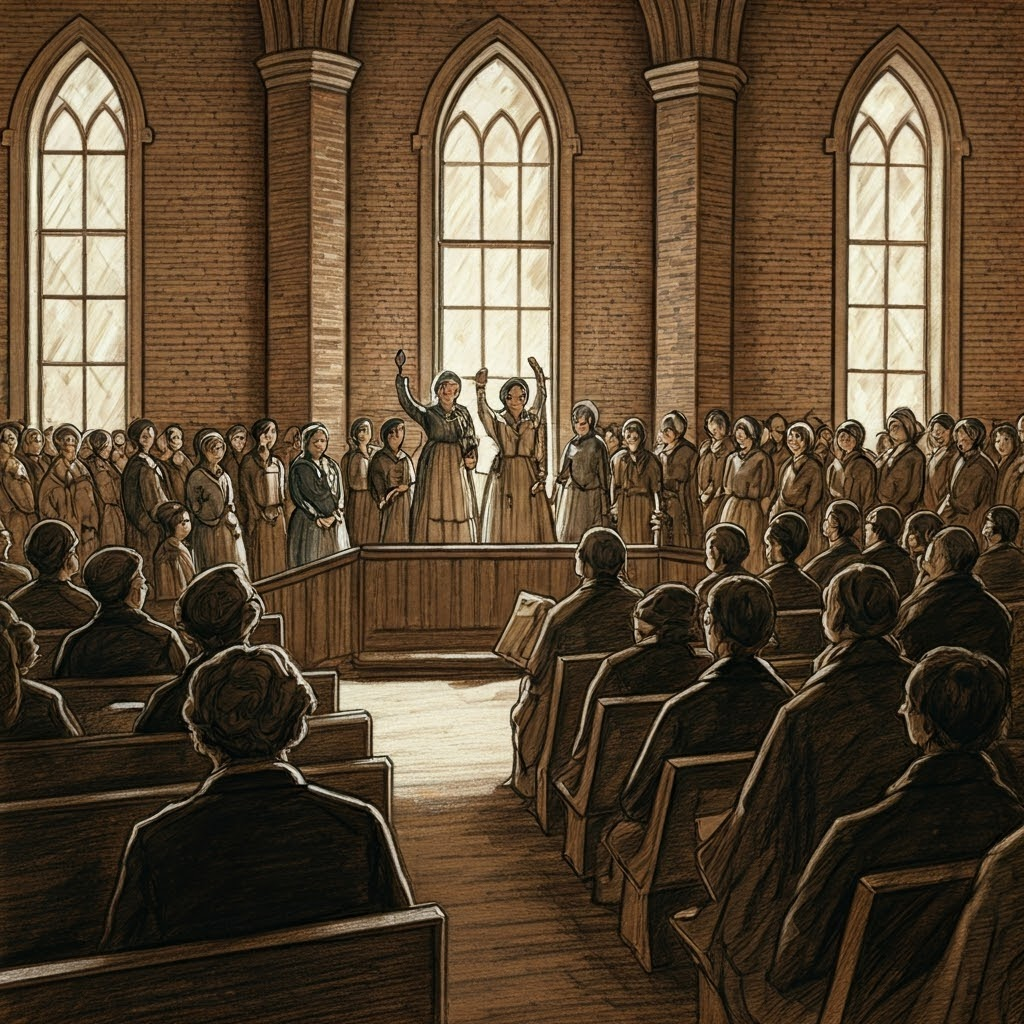

In July 1848, a crowd gathered in a small brick church in Seneca Falls, New York. Most were women, a few were men, and nearly all had come because they believed something was deeply wrong with how society treated women. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, frustrated by years of being ignored at anti-slavery meetings, teamed up with Lucretia Mott, a seasoned Quaker activist, to organize the country’s first women’s rights convention. The church felt more like a storm than a social club.

Out of that meeting came the famous Declaration of Sentiments, a document that boldly rewrote the US Declaration of Independence with one small, world-shaking twist: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.” The declaration listed the many ways women were held back—no right to vote, no property rights, no control in marriage, and no voice in laws that ruled their lives. When Stanton proposed the radical demand for the vote, even some supporters hesitated. It took a steady, convincing speech by Frederick Douglass, the well-known Black abolitionist, to turn the tide. The demand stayed.

Out of that meeting came the famous Declaration of Sentiments, a document that boldly rewrote the US Declaration of Independence with one small, world-shaking twist: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.” The declaration listed the many ways women were held back—no right to vote, no property rights, no control in marriage, and no voice in laws that ruled their lives. When Stanton proposed the radical demand for the vote, even some supporters hesitated. It took a steady, convincing speech by Frederick Douglass, the well-known Black abolitionist, to turn the tide. The demand stayed.

Petitions, Parades, and Pioneers

When you’re not allowed in the halls of power, you get creative about being heard. Early suffragists took up petitions. In 1866, British reformers organized the first mass petition for women’s votes—1,500 signatures, handwritten and hand-delivered to Parliament. Each name was an act of courage, as signing could mean ridicule, job loss, or worse. In the US, Susan B. Anthony once lugged petitions weighing over 100 pounds into Congress.

Parades and public speeches became new tools. Sojourner Truth, born into slavery, gave her famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech, blending the fight against slavery with the demand for women’s rights. In 1908, British suffragettes staged a massive march in London—30,000 women in white dresses, banners flying in the rain. In New Zealand, Kate Sheppard’s face would later appear on the $10 note, but first she led campaigners who knocked on doors across the country, gathering signatures and making speeches. These were ordinary women—teachers, factory workers, mothers—rallying neighbors and changing minds one at a time.

Parades and public speeches became new tools. Sojourner Truth, born into slavery, gave her famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech, blending the fight against slavery with the demand for women’s rights. In 1908, British suffragettes staged a massive march in London—30,000 women in white dresses, banners flying in the rain. In New Zealand, Kate Sheppard’s face would later appear on the $10 note, but first she led campaigners who knocked on doors across the country, gathering signatures and making speeches. These were ordinary women—teachers, factory workers, mothers—rallying neighbors and changing minds one at a time.

New Zealand: First at the Polls

If you want proof that big changes can start on the edge of the map, look at New Zealand. In the late 1800s, it was a young, remote country, but bold in its politics. For years, Kate Sheppard and her fellow campaigners did the hard, repetitive work—writing thousands of letters, publishing pamphlets, and organizing the world’s largest suffrage petition at the time, with nearly 32,000 signatures (in a country of fewer than a million). The opposition—politicians, clergy, and some business owners—warned that allowing women to vote would ruin families or even collapse Western civilization. They were sincere, but spectacularly wrong.

On September 19, 1893, the New Zealand Parliament passed the Electoral Act, making New Zealand the first self-governing country to grant women the vote. When election day came, women lined up at polling stations, some bringing babies, baskets, or farm tools. Newspapers as far away as London and New York reported the news with a tone that was half wonder, half disbelief. The shockwaves were immediate. Within twenty years, parts of Australia, Europe, and North America followed. Leaders as far away as Finland and the Western US started to ask: “If New Zealand can do it, why can’t we?” The New Zealand victory showed the world something simple and dangerous to the old order: ordinary people, no matter how far from the centers of power, can change everything by refusing to give up.

On September 19, 1893, the New Zealand Parliament passed the Electoral Act, making New Zealand the first self-governing country to grant women the vote. When election day came, women lined up at polling stations, some bringing babies, baskets, or farm tools. Newspapers as far away as London and New York reported the news with a tone that was half wonder, half disbelief. The shockwaves were immediate. Within twenty years, parts of Australia, Europe, and North America followed. Leaders as far away as Finland and the Western US started to ask: “If New Zealand can do it, why can’t we?” The New Zealand victory showed the world something simple and dangerous to the old order: ordinary people, no matter how far from the centers of power, can change everything by refusing to give up.

Sparking a Global Movement

What started as scattered petitions and a meeting in a church hall grew into a movement that circled the globe. Early suffragists were not saints or superheroes—they were people who got tired of waiting for someone else’s permission. Their spark became a fire, lighting paths for others who believed their voice mattered. Every signature, every speech, every brave step laid the groundwork for the fights—and the victories—that came next. If you ever wonder what difference one determined voice can make, remember: every revolution starts with someone asking an uncomfortable question—and refusing to accept silence as an answer.