When the World Stood Still: The Old Order and Its Cracks

The Center of Everything

Imagine standing in a quiet night field as stars wheel overhead. Earth feels steady under your feet, while the sky appears to glide around you. For centuries, this sight shaped the geocentric view of the cosmos.

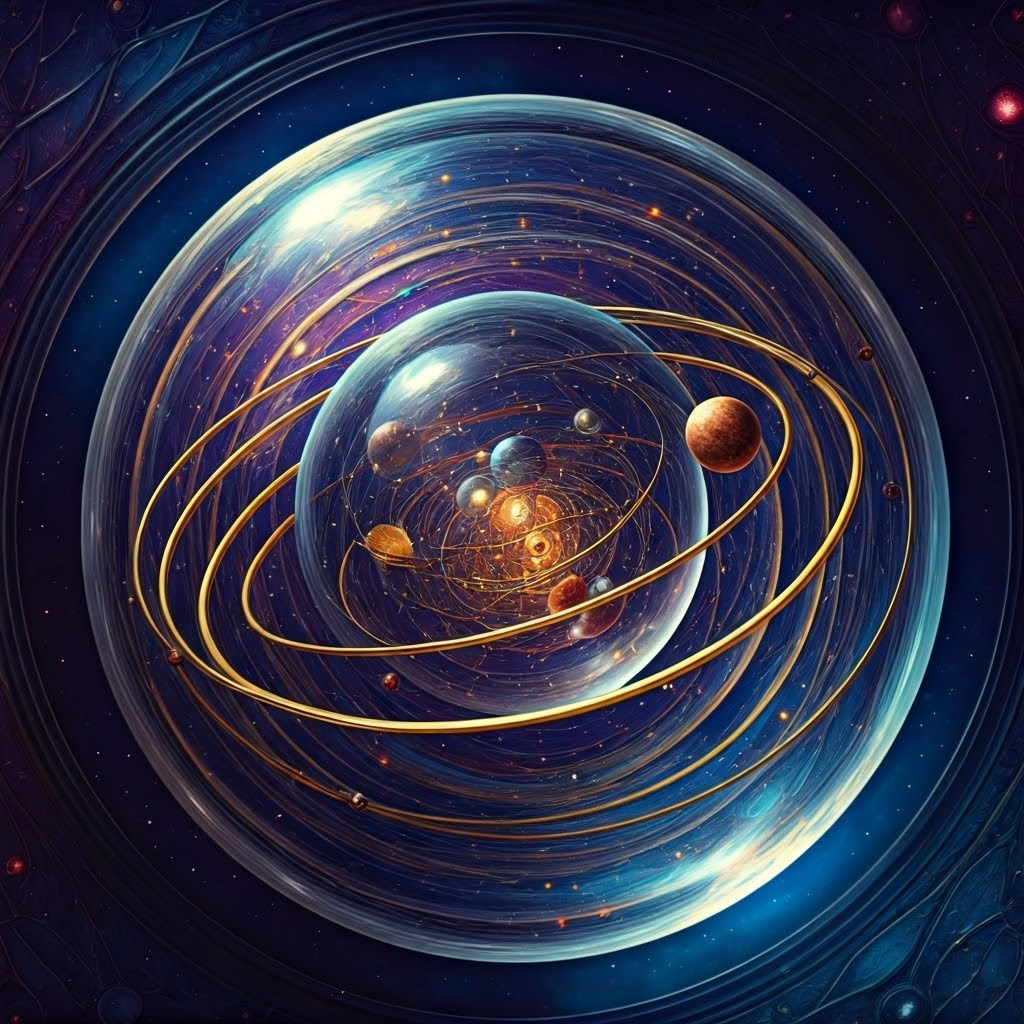

Ptolemy turned that feeling into a structured model. Picture nested crystal spheres with Earth in the middle. Each sphere carries the moon, a planet, or the stars, all moving in graceful circles.

The order began with the moon, then Mercury and Venus, followed by the sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and finally the fixed stars. To explain odd planet paths, Ptolemy added small circles—called epicycles—spinning atop larger ones.

People trusted this system because it matched Aristotle’s vision of perfect heavenly spheres and placed humanity at the story’s heart. Church teachings wove it into faith, giving cosmic order spiritual weight.

Signs in the Sky

Mars usually drifts eastward but sometimes halts, slides west, then moves on. This puzzling retrograde motion forced astronomers to stack ever more epicycles onto their diagrams.

Sharper observations exposed new flaws. Planets brightened when closer to Earth, hinting at shifting distances the geocentric scheme struggled to explain without extra patches.

Why Change Was Hard

Challenging the old model threatened the very identity of society. Earth’s fixed spot gave people meaning. Both philosophers and church leaders leaned on that certainty to answer life’s biggest questions.

Questioners faced ridicule or worse. Many asked, If Earth moved, why don’t we feel it? Why don’t birds lag behind? Doubts had social and spiritual costs, so only the bold persisted.

Yet the cracks widened. Inconsistent epicycles, shifting planet brightness, and new stars nudged minds toward a daring question: What if Earth moves—and the cosmos is far grander than anyone imagined?