Seeds, Beasts, and Bugs: The Great Swap

A World Turned Upside Down

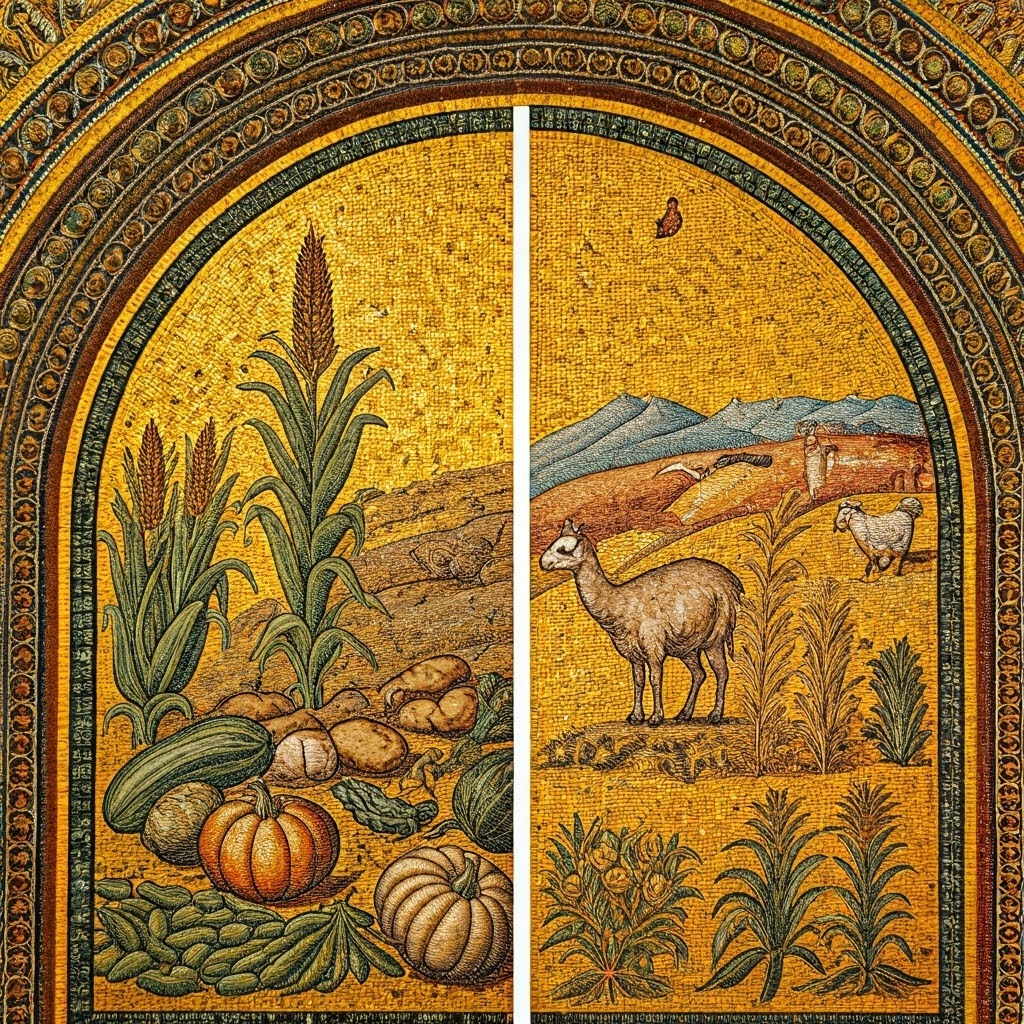

Look at your dinner plate. Picture it without potatoes or tomatoes. Before 1492, Europe, Asia, and Africa had never seen these foods. The Americas, meanwhile, had no wheat bread, coffee, or rice.

For centuries, the Old World lived on wheat, barley, and rye, with meat from cows, sheep, and chickens. Across the ocean, daily meals relied on maize and beans. Riders or draft animals were rare—only llamas and alpacas served that role in South America.

The Old World also shared germs like smallpox, measles, and influenza, building some resistance. The Americas had none, so first contact unleashed shocking consequences.

The Arrival of New Foods

Settlers soon planted wheat from Mexico to Argentina, craving familiar bread. They also introduced sugarcane, which turned Caribbean and Brazilian fields into vast plantations. Coffee followed, thriving in the highlands of Colombia and Central America.

American crops reshaped Old World diets. The potato delivered more calories per acre than any earlier European staple, fueling population growth in places like Ireland and Russia. Maize became a cornerstone grain in Africa and parts of Asia. Tomatoes brightened Mediterranean dishes, while cacao and chili peppers added luxury and heat worldwide.

Animals on the Move

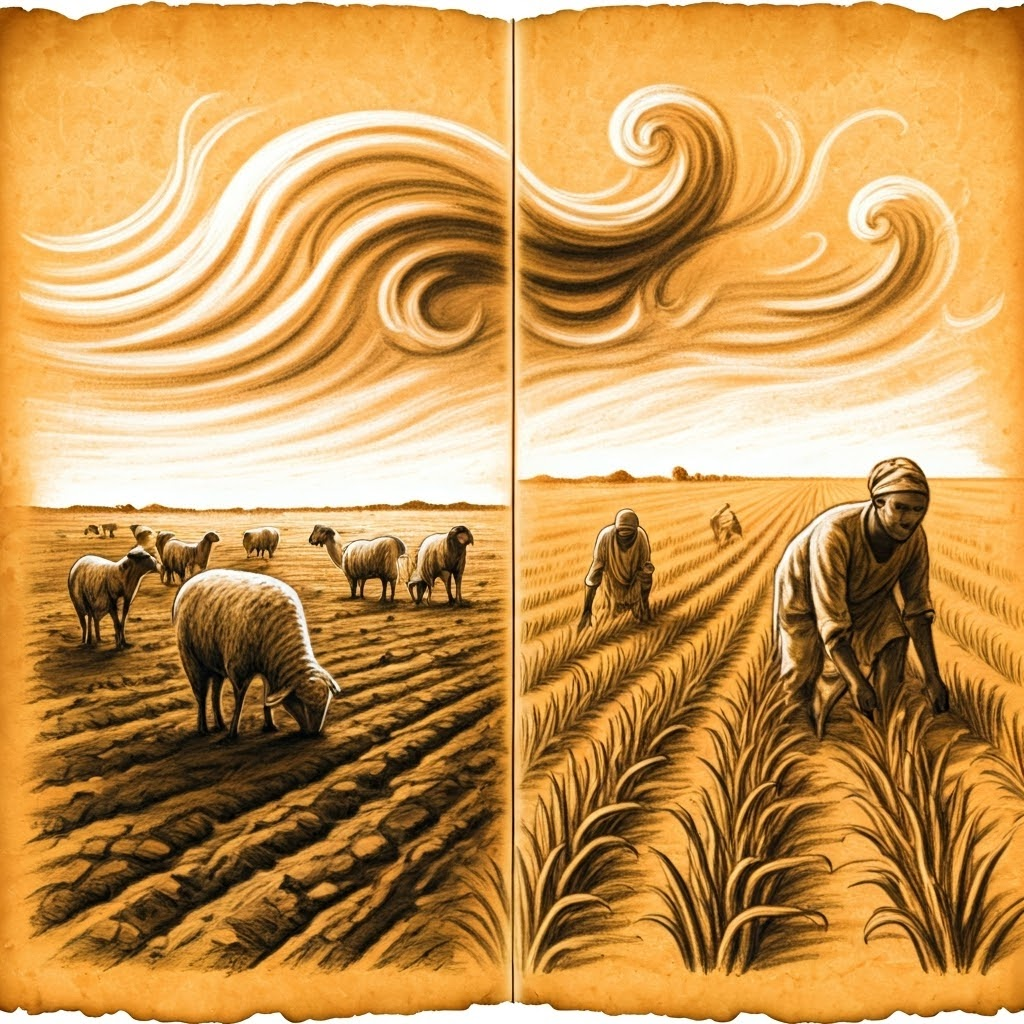

The introduction of the horse transformed Indigenous life on the Great Plains—hunting and travel suddenly sped up. Pigs roamed Caribbean islands, breeding fast and devouring crops. Cattle and sheep grazed new grasslands from Mexico to Argentina, paving the way for ranching.

Daily routines shifted. Riding replaced long treks on foot, and dairy foods such as cheese entered local diets. Yet roaming livestock often displaced native plants and animals, sparking new conflicts over land.

Invisible Invaders

The deadliest newcomers were microbes. Smallpox swept ahead of European settlers, sometimes killing 60–90 percent of Indigenous populations within decades. Entire communities vanished almost overnight.

Measles and influenza soon followed, adding fresh waves of suffering. Lacking immunity, Native peoples faced the greatest mortality event in recorded history caused by disease.

Unwanted Guests: Invasive Species

Seeds and pests tagged along. Dandelions and thistles sprouted from wheat sacks, outcompeting native plants. Rats and mice slipped from cargo holds, raiding grain stores and upsetting local ecosystems.

The swap worked both ways. In Africa, imported maize sometimes edged out traditional grains, altering fields and diets. Invasive plants and animals kept reshaping landscapes—often in ways settlers never foresaw.

Every pasture, potato, and echoing hoof today reflects the Columbian Exchange. This grand shuffle of seeds, beasts, and bugs still molds what we eat and how we live—and its story continues.