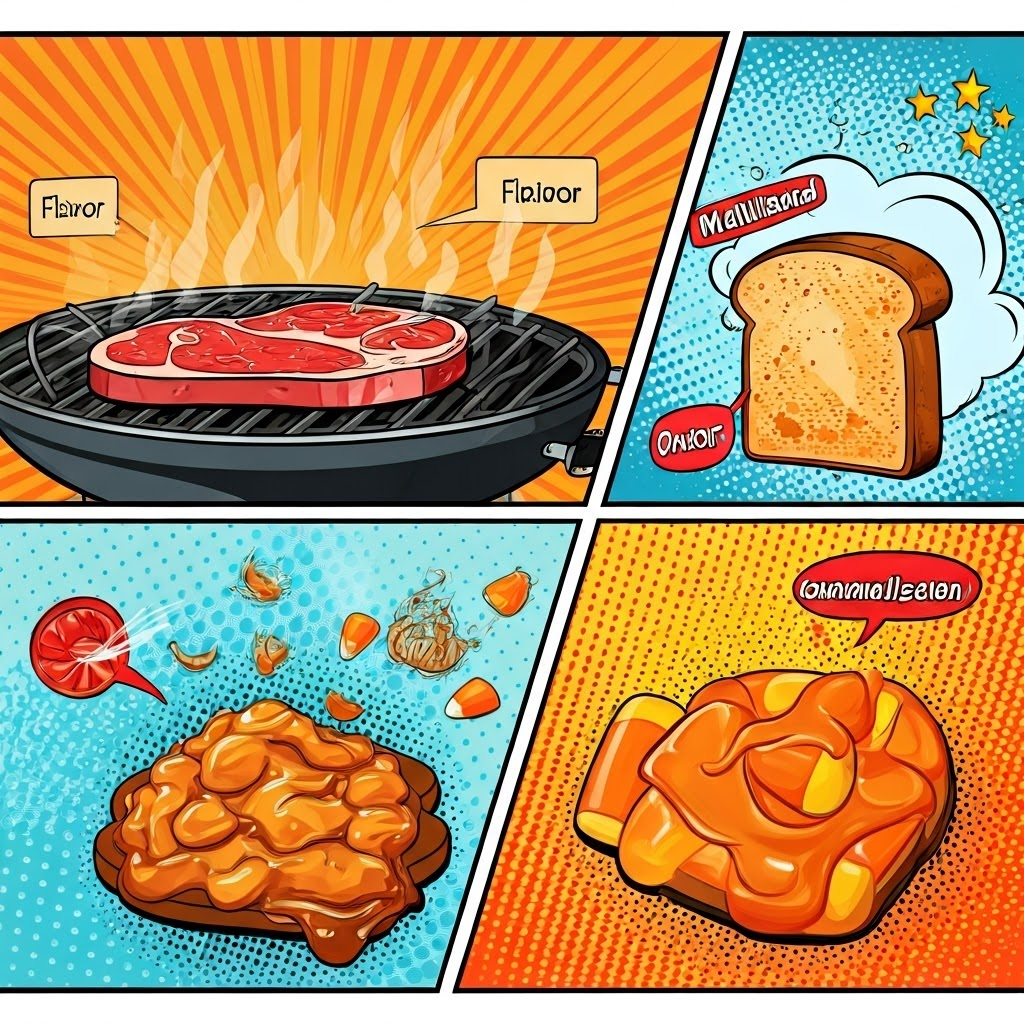

Unlocking Flavor: The Science Behind Browning

When you lift a golden loaf from the oven or smell the edge of a sizzling grilled cheese, you’re tasting the Maillard reaction. Heat meets proteins and sugars. New aromas bloom. Rich color forms. This simple reaction turns everyday food into something memorable.

What Really Happens When Food Browns

Heat above 300 °F (150 °C) kicks things off. Amino acids from proteins meet reducing sugars like glucose or fructose. They combine in fast, unpredictable bursts. Hundreds of flavor molecules appear—some nutty, some toasty, some meaty. These layers give browned food its depth.

A well-seared chicken breast tastes worlds apart from a boiled one. Color signals flavor. Robert Wolke calls browning the place where the “flavor fireworks” happen. Think roasted potatoes, toasted bagels, or a steak’s crust—they all draw power from this reaction.

Amino Acids, Sugars, and the Magic Equation

Amino acids live in meat, eggs, dairy, grains, and veggies. Reducing sugars include glucose, fructose, and lactose. Sucrose can split into reducing sugars when heated. Together with strong heat, they start the Maillard chain.

Bread dough supplies proteins and sugars that react in the oven. Coffee beans do the same in the roaster. Potatoes and steak rely on surface dryness and high heat. Moist cooking like boiling can’t reach these conditions, so browning stalls.

Maillard vs. Caramelization: Not the Same Thing

Caramelization needs only sugar and starts around 340 °F (170 °C). It yields sweeter notes—caramel, toffee, honey. Maillard browning needs protein plus sugar, which brings deeper, more savory flavors. That’s why steak crust isn’t candy-sweet even though both processes create brown color.

Remember: toast equals Maillard; caramel equals caramelization. Oven-roasted veggies often blend both, giving a sweet-savory punch. Knowing the difference helps you control taste.

Why This Matters in Your Kitchen

To coax depth, keep surfaces dry, use high heat, and avoid crowding. Foods rich in both proteins and sugars—bread, potatoes, steak—brown easily. Others, like onions, may need a pinch of sugar. A bit of patience lets heat, proteins, and sugars perform their symphony, giving every dish a richer finish.