When the Heavens Wobbled: The First Doubts

The Old Order: Cosmos, Body, and Medicine

Picture late medieval Europe. The Earth appears fixed at the universe’s heart. Above, bright bodies glide in perfect circles.

This cosmic map shapes daily life. People schedule prayers and harvests by the sky’s rhythm. Medicine follows Galen’s four humors—blood, phlegm, black bile, yellow bile.

A headache signals imbalance, not germs. Hospitals echo Galen’s words. Authority discourages doubt; church and crown guard tradition.

Copernicus: Moving the Sun

In Poland, mathematician Nicolaus Copernicus reviews puzzling planetary loops, especially Mars’s backward dance.

He flips the model: place the sun in the center, let planets circle it. The messy motions suddenly align—no extra epicycles.

His book De revolutionibus appears on his deathbed. The claim feels risky, yet it plants vital skepticism.

Vesalius: Drawing the Body Anew

Medical schools recite Galen while cutting pigs. Human anatomy stays second-hand. Andreas Vesalius changes that.

He dissects real bodies and drafts precise charts. Errors emerge—human livers differ from apes, some “organs” simply do not exist.

His Fabrica proves old masters can be wrong. Observation now guides medicine.

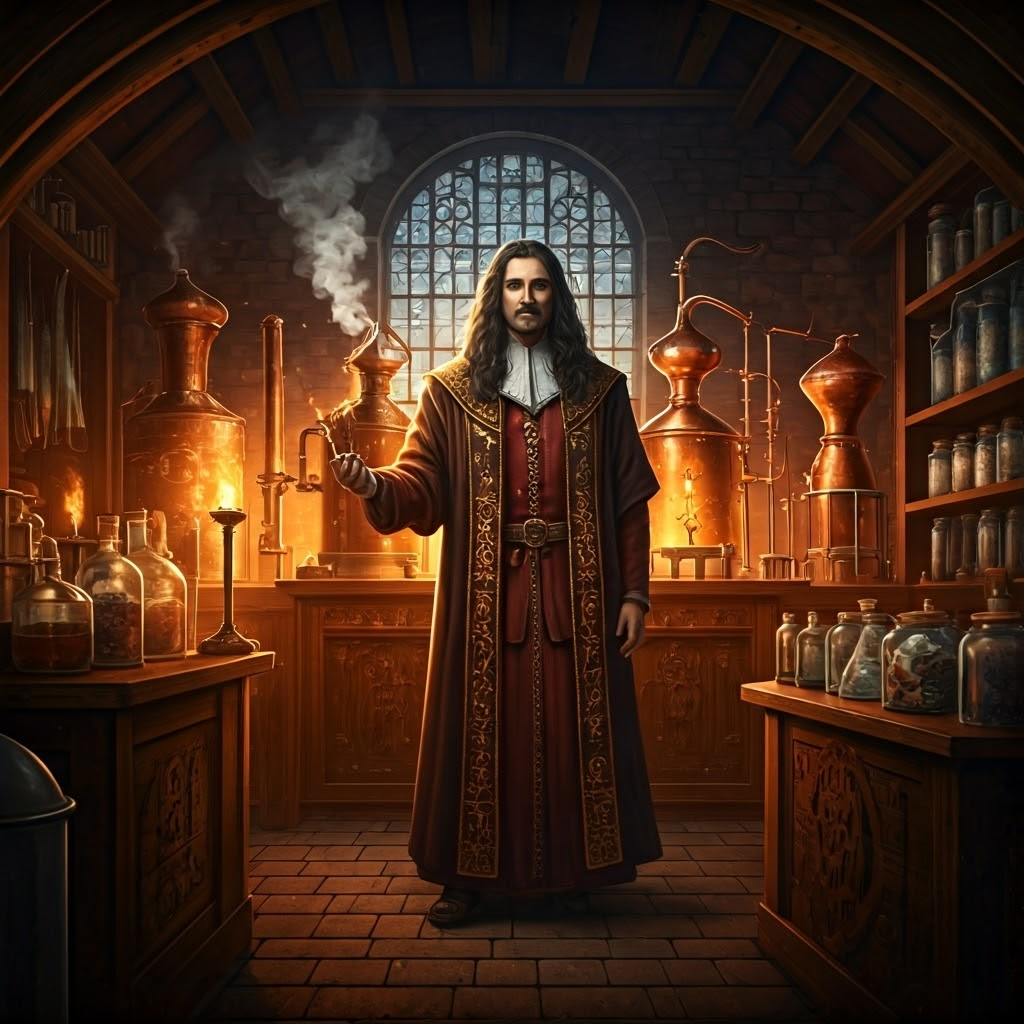

Paracelsus: The Alchemist Doctor

Paracelsus roams Europe with outspoken flair. He insists medicine use chemistry, not only humors.

He tests mercury, sulfur, and salt as treatments and torches dusty texts in protest. Some cures prove harmful, yet his daring sparks early pharmacology.

As an outsider, he asks questions insiders avoid and keeps the field moving.

Not Just Doubt—A Method

Copernicus, Vesalius, and Paracelsus share one habit: they question inherited answers.

Their courage is personal—a scholar scribbling alone, an anatomist with a scalpel, an alchemist testing new cures.

Evidence overrides tradition. Once people ask sharper questions, the old worldview cracks, and modern science quietly begins.