The Spark: Ideas That Lit the Fire

When you hear the word liberty you might picture freedom for all. Yet in the 1700s the idea felt new and complicated.

Philosophers began challenging kings, priests, and customs. They urged people to think for themselves and to demand a voice in government.

Opinions soon clashed over who deserved freedom. Thomas Paine claimed the colonies should rule themselves, calling it simple common sense.

He later wrote that natural rights—safety, justice, and freedom—belong to everyone. His words stirred crowds and fueled debate.

Reality lagged behind ideals. Many limited equality to white property-owning men, leaving women, the poor, and the enslaved outside the promise.

English author Mary Wollstonecraft refused to stay silent. In 1792 she argued women lacked opportunity, not ability, and deserved the same education as men.

She asked a sharp question: if all people are born equal, why treat girls as lesser? Her challenge forced society to rethink fairness.

Pamphlets and books reached far beyond scholars. A young woman reading in secret or workers debating in a tavern felt hope ignite.

The Enlightenment pushed people to question long-held beliefs—yet it also exposed painful gaps between words and actions.

Contradictions in the Age of Reason

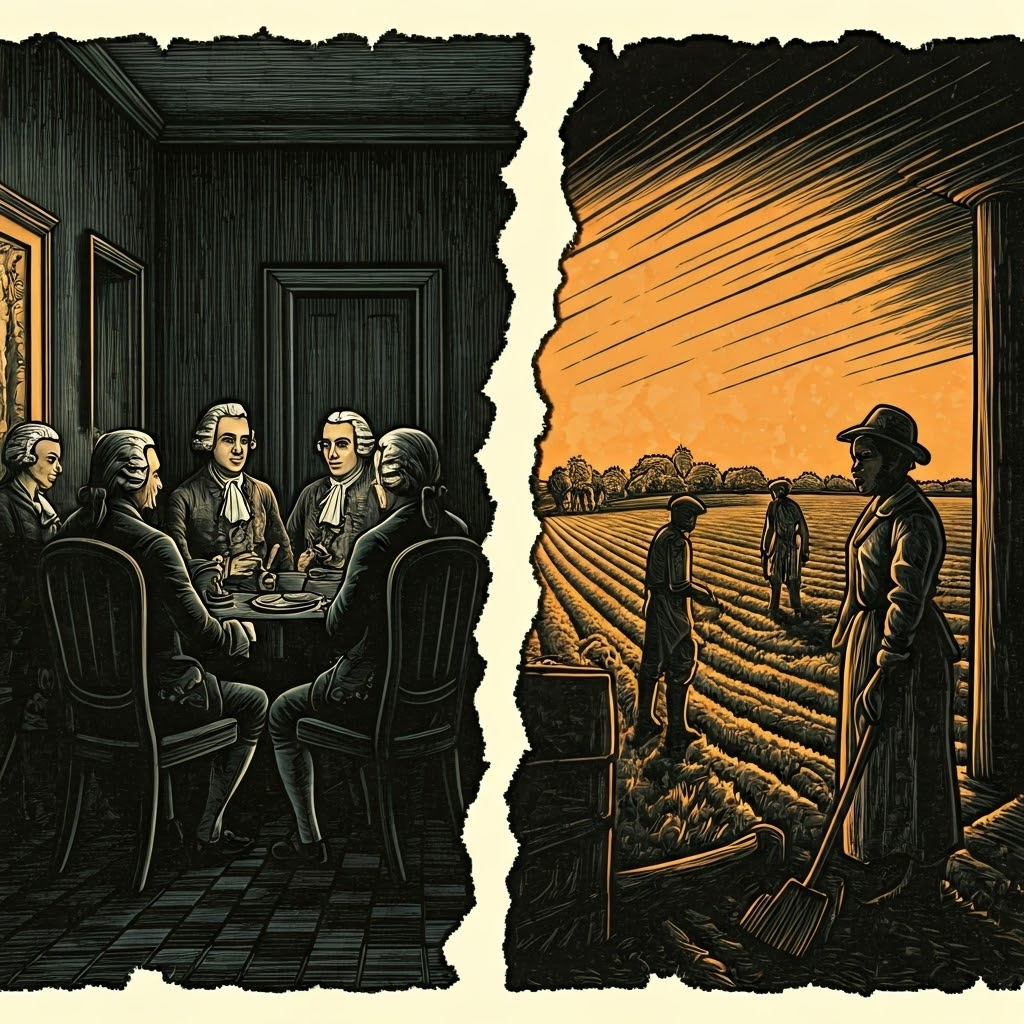

Thinkers praised reason, but whole economies still relied on slavery and strict limits on women. The mismatch was glaring.

American colonists demanded freedom from Britain, yet many owned enslaved people. Declaring “all men are created equal” rang hollow in practice.

Free Black mathematician Benjamin Banneker wrote to Thomas Jefferson, urging him to apply the same compassion he sought from Britain to the enslaved.

Women noticed the gap as well. Abigail Adams reminded her husband that a new nation should not ignore half its citizens.

Some leaders postponed change, while voices like Paine and Wollstonecraft kept pressing. Progress met backlash, inspiration met reality.

Words That Moved People

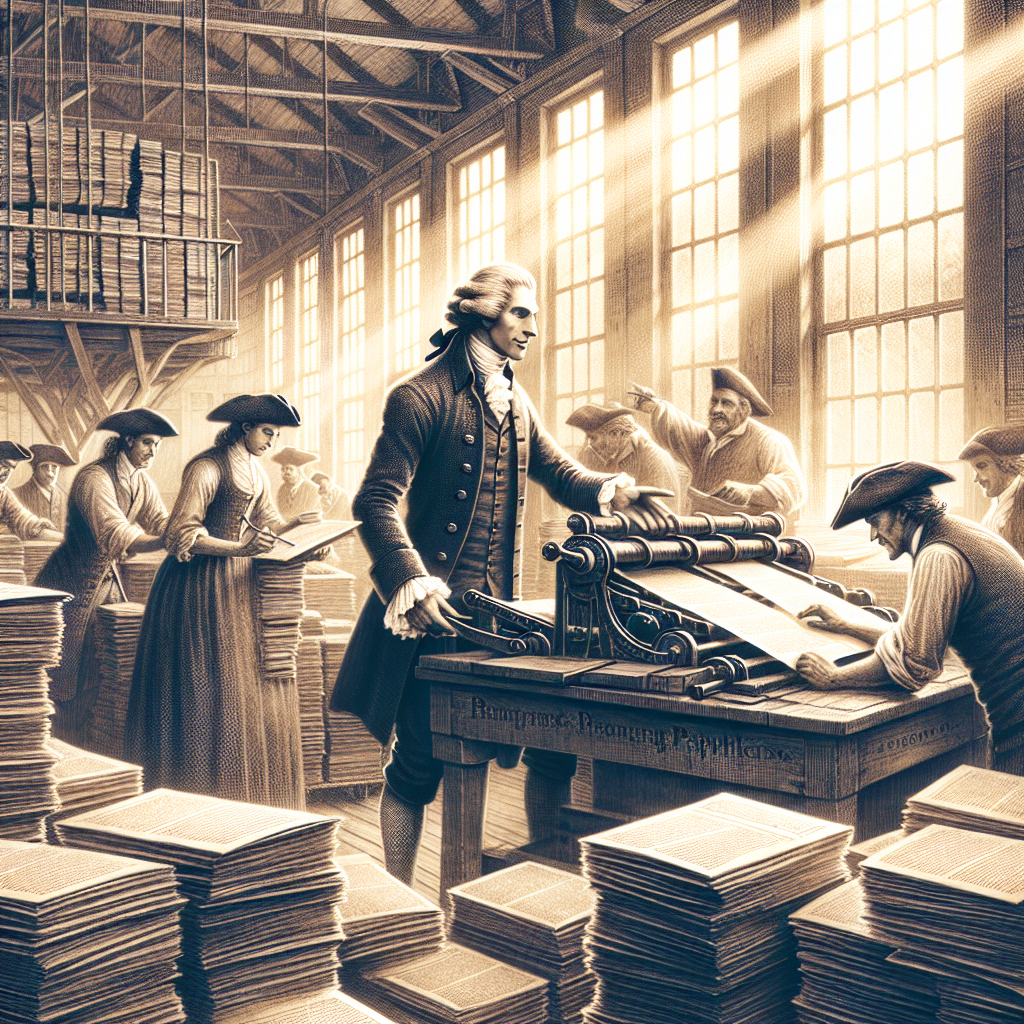

Ideas are sparks; print culture is dry kindling. Books and pamphlets spread freedom’s call beyond elite circles.

Paine’s “Common Sense” sold over 100,000 copies in months, read aloud in taverns and homes, emboldening ordinary people.

Wollstonecraft’s work reached teachers and early suffragists. The right book could connect isolated dreamers into a movement.

Public debate turned into a lively theater. Governments tried to silence printers, fearing the spread of bold ideas.

Even learning to read became resistance. Reading allowed direct access to new thoughts; writing let people join the argument.

Today, sharing an article or signing a petition continues that tradition. Big change often starts with simple words and stubborn questions.