Time Travelers: Reading Earth’s Deep History

Picture Earth’s lifespan as a single calendar year. Dinosaurs stride in mid-December. Humans rush onstage in the year’s final minutes. Rocks record everything in between—each layer a quiet chapter of volcanoes, seas, and wandering continents.

The Clock Beneath Our Feet

Geological time stretches back 4.6 billion years. Continents drift. Mountains rise, erode, and rise again. Life appears, thrives, and vanishes. Compress that story into a year, and our species blinks into view just before midnight. Each rock layer stores a moment from this expansive diary.

Why Deep Time Matters

Deep time reminds us that hills, plains, and even mighty peaks are brief features. The Grand Canyon needed roughly six million years to form, while the Himalayas still rise today. Recognizing such slow shifts fosters patience and underscores Earth’s constant, silent motion.

Eons, Eras, and the Big Picture

Geologists organize time like nested maps. Eons span hundreds of millions of years. Eras divide eons, periods split eras, and epochs zoom in further. Slotting rocks and fossils into these units builds a framework for Earth’s epic narrative.

Hadean marks Earth’s fiery birth. Archean follows with the first simple bacteria. In Proterozoic, oxygen rises and complex cells evolve. Phanerozoic—our current eon—hosts most visible life, including dinosaurs, mammals, and us.

The Phanerozoic’s eras read like main story arcs: Paleozoic (old life), Mesozoic (middle life—dinosaurs), and Cenozoic (recent life—mammals dominate). Each era fragments into periods, then epochs, charting finer environmental swings and species changes.

A Familiar Example

Limestone beside a farm road might have formed in a warm, shallow sea that blanketed today’s Kansas. Sandstone could trace wind-sculpted deserts or old river deltas. Every outcrop preserves a snapshot of vanished climates and wandering continents.

Fossils: Nature’s Time Capsules

A fossil is any preserved sign of ancient life—shells, bones, footprints, burrows. Rapid burial shields remains from decay. Minerals seep in, turning tissue to stone. Index fossils such as ammonites lived briefly yet spread widely, making them ideal markers for dating rock layers.

The Case of the Missing Dinosaurs

Suppose you find a dinosaur femur. Layers above hold small mammal teeth; layers below do not. You’ve reached the Mesozoic-Cenozoic boundary—the slice where non-avian dinosaurs end and mammals rise. This abrupt fossil turnover sets a vivid line between eras.

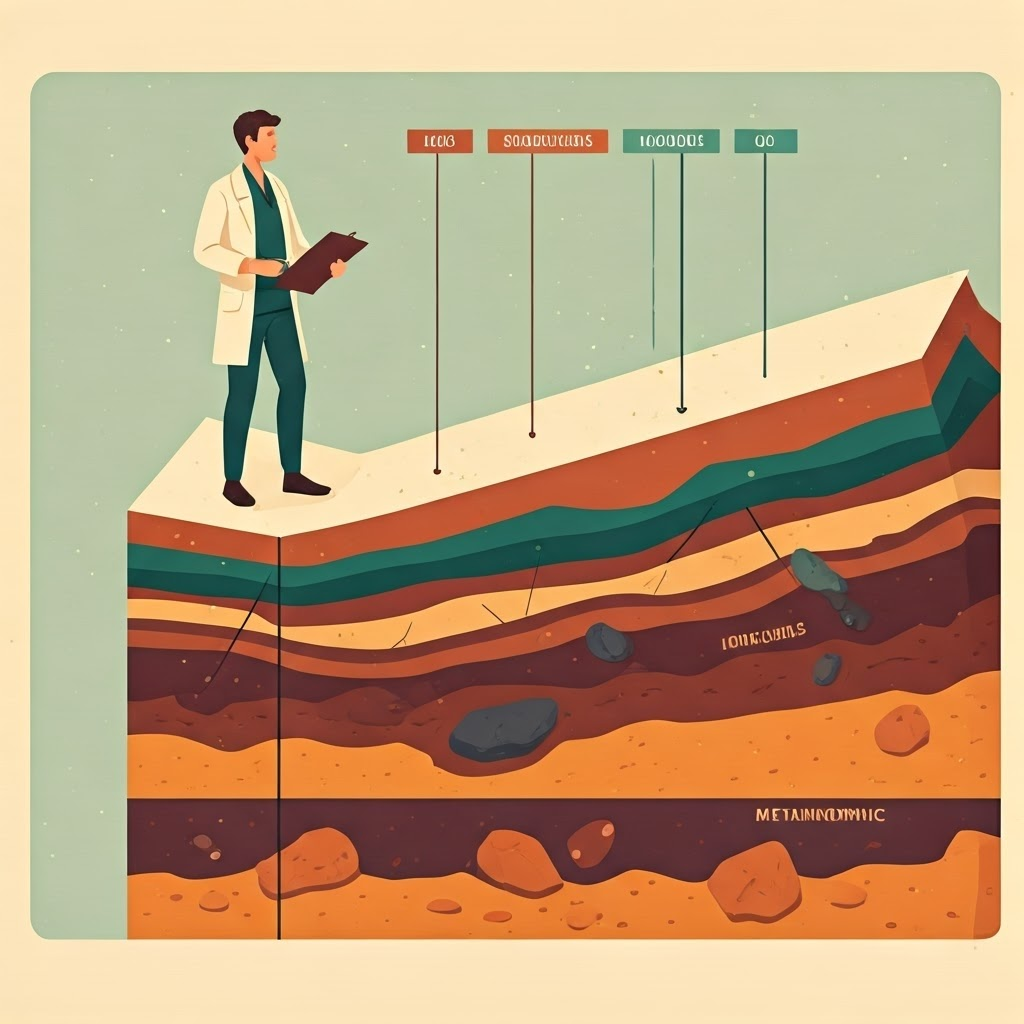

Rocks as Storytellers

Igneous rocks crystallize from cooling magma, recording volcanic episodes. Sedimentary rocks pile up in water or wind, often cradling fossils. Metamorphic rocks transform under heat and pressure, revealing deep burial and tectonic stress. Texture, minerals, and color let us decode these tales.

Unlocking the Local Story

Visit a nearby quarry or cliff. Is the rock gritty like sandstone or smooth like limestone? Does it contain shells, ripple marks, or volcanic crystals? Matching these clues to known environments lets you rebuild your area’s personal timeline of oceans, rivers, or eruptions.

Seeing the Timeline in Everyday Life

Once you learn to read rocks, city sidewalks and mountain trails alike transform into an open-air archive. Fossil imprints, sediment bands, and metamorphic folds whisper stories of deep, patient change. Embracing this perspective turns every step into an encounter with history written in stone.