From Muddy Paths to Waterways: The First Big Leap

Life on the Old Roads

Moving goods in 1700s England was gruelling. Roads were little more than muddy footpaths that dissolved after rain. Travelers often walked or joined a packhorse string. One horse carried 100–150 kilos, so even long caravans moved small loads at a crawl.

Every town managed its own paths, creating a patchwork of dirt, stones, and shaky causeways. Wagons snapped axles, and winter could freeze traffic for weeks. A 1747 visitor reached Lancashire in horror, needing several days for 30 miles while fearing each boggy turn.

Poor roads capped what people could move. Heavy coal or timber stayed local. Prices rose with distance, so most people lived and died close to home. Shipping fresh milk or fruit was unthinkable—a far cry from today’s global groceries.

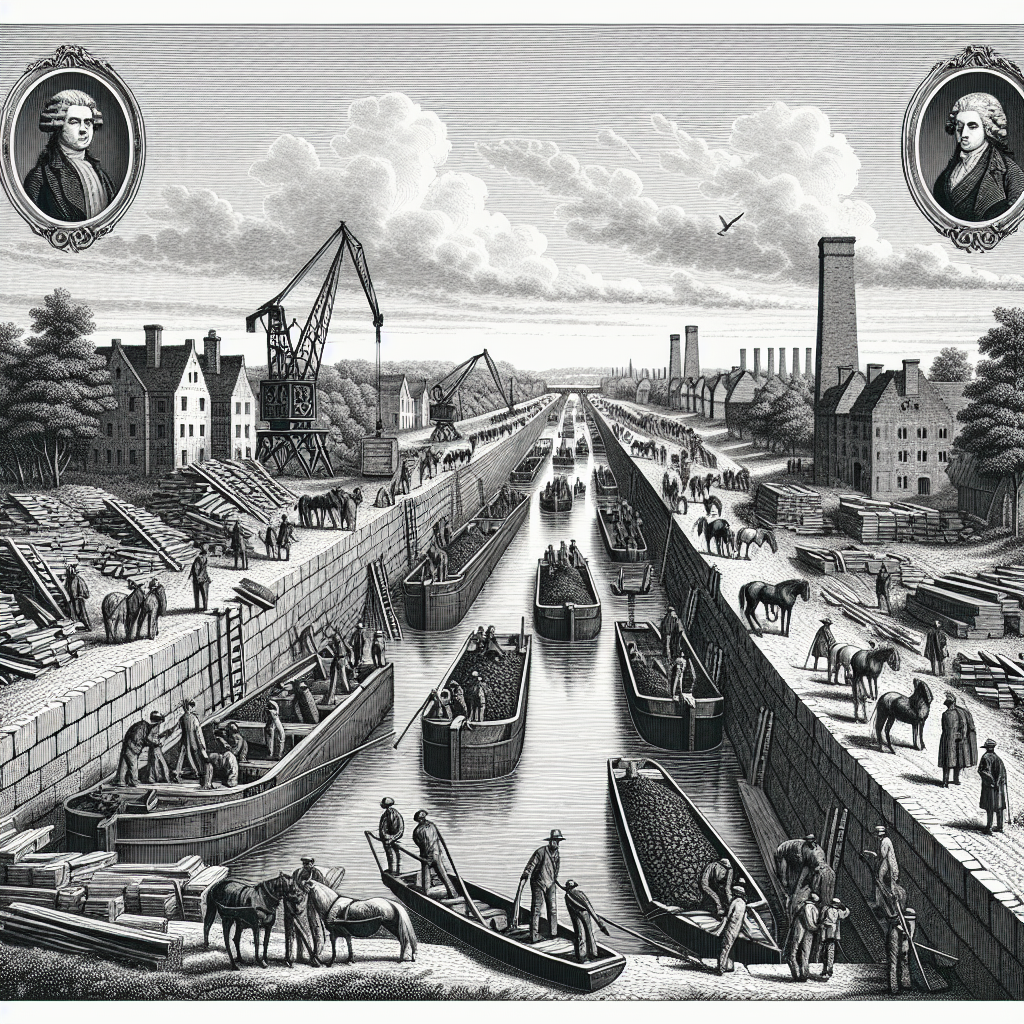

Digging Deep: The Canal Revolution

The 3rd Duke of Bridgewater faced costly coal runs to Manchester. He hired James Brindley and John Gilbert, who proposed a canal—a horse-towed water road that let barges glide gently downhill instead of jostling over mud.

Engineers had to cross the River Irwell without steep climbs. Brindley’s Barton Aqueduct carried water over water, drawing crowds amazed at boats “in the sky.” Where hills loomed, locks lifted or lowered craft through gated chambers of rising or falling water.

The first Bridgewater stretch opened in 1761. Manchester’s coal price halved almost overnight, sparking nationwide canal-mania. Within 50 years, Britain dug 4,000 miles of waterways, and engineers like Thomas Telford and John Rennie became household names.

Waterways at Work

One horse could tug a barge holding 30 tons—ten times a packhorse team. Coal, iron, and grain now traveled far, seeding new industries. Towns such as Stourport sprang up “on the cut,” thriving on steady supplies.

Transport costs plunged. Hauling a ton of coal 30 miles cost a fraction of the old rate. Makers could sell wider, fueling competition and invention. Yorkshire wool raced to London, while Staffordshire pottery reached homes nationwide.

Daily life also shifted. Barges began carrying passengers, offering a calmer ride than stagecoaches. Some crews ran floating shops, spreading goods and news to canal-side villages. Phrases like “off the beaten track” grew from canal slang, as waterways shrank the muddy world.

Canals solved a problem roads never could: scale. Before steam trains, nothing matched a barge for capacity and reliability. These water highways were the first big leap that made Britain feel smaller and paved the way for later revolutions in steam and steel.