How It All Began: The Roots of Environmental Justice

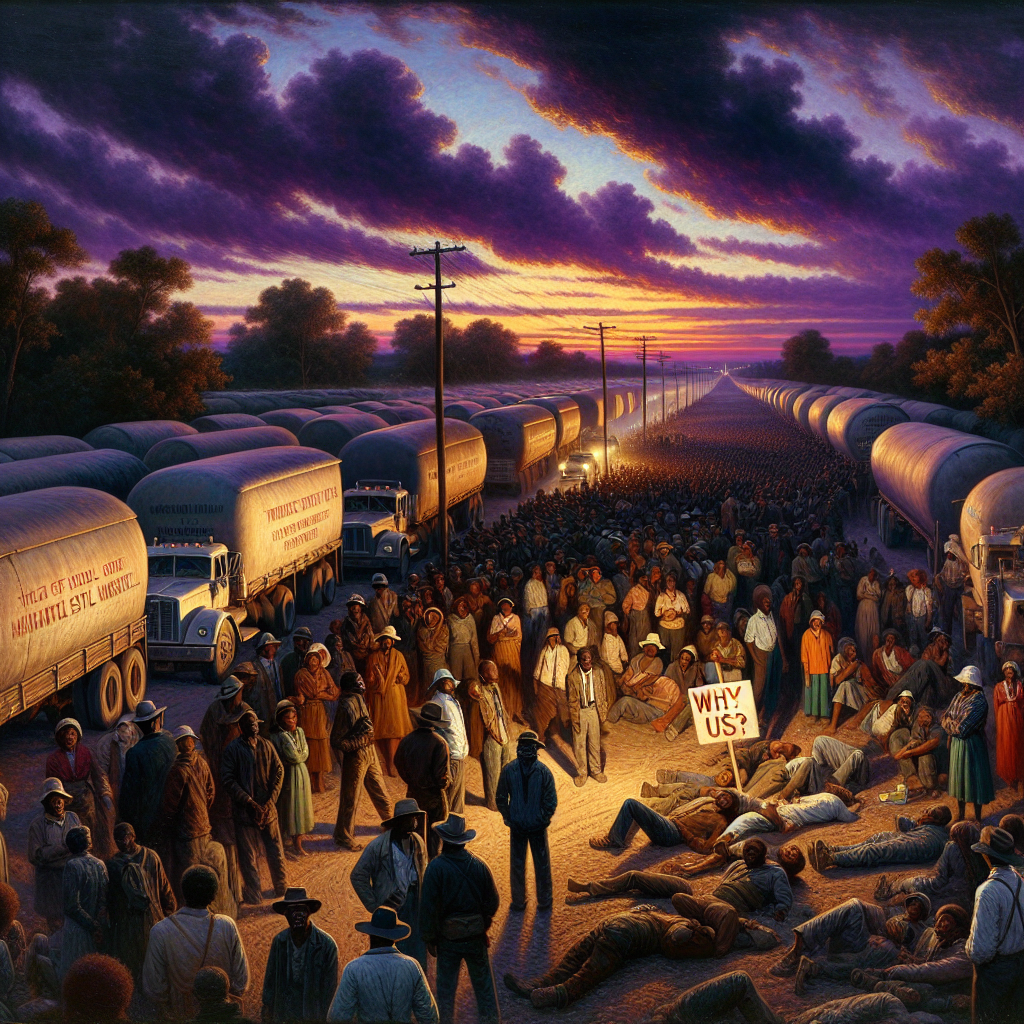

In 1982 residents of rural Warren County, North Carolina, lay in the path of trucks hauling soil tainted with PCBs. Most protesters were Black. They risked arrest because the state had chosen their community for a toxic landfill they neither created nor wanted.

The community did more than complain. Church leaders, farmers, and civil-rights veterans marched side by side and chanted for clean land and water. Police arrested over 500 people—the South’s largest civil disobedience action since the 1960s. News of the standoff spread fast and inspired other polluted towns.

The landfill was built, yet the struggle coined a new phrase: environmental justice. Warren County proved that fights over pollution are also fights over power and voice.

Across America the worst pollution often sits where Black, Latino, Indigenous, or poor families live. Garbage burners in the Bronx and chemical plants along the Mississippi line up with these neighborhoods because officials think they will meet the least resistance.

The pattern reaches worldwide. Toxic dumps and pipelines snake through places with the least money or political power. In 1987 the report Toxic Wastes and Race showed that race mattered more than income when deciding where hazards go. Communities of color were not unlucky—they were targeted.

The study shocked the public and fueled protests, lawsuits, and policy shifts demanding equal protection from pollution for everyone.

Voices That Changed the Game

Sociologist Robert Bullard, often called the father of environmental justice, mapped landfills and incinerators in Houston during the 1970s. His research proved that pollution was color-coded and spread the issue from local courts to national debate.

Physicist Vandana Shiva linked big development projects to struggles of small farmers and women in India. She championed food sovereignty, insisting rural communities control what they grow and eat, making environmental justice a truly global movement.

Brazilian rubber tapper Chico Mendes organized workers to shield the Amazon and their livelihoods. His belief that social justice and environmental protection are inseparable now anchors modern environmental thought. His 1988 assassination underscored the high stakes of this work.

These leaders remind us that pollution always carries a human story. The most damaged places are usually where people already face hardship, yet organized communities can—and do—drive real change.