How the Internet Learned to Chop: The Birth of Packets

Early networks reserved an entire line for one conversation. That dedicated path wasted capacity because silence still blocked others from using the line. Circuit-switching made sense for voice calls yet felt extravagant for data.

Why chopping data makes sense

Picture mailing a thick book in one box. If the box jams the slot, nothing moves. Split the pages into envelopes instead, and most arrive even if one lags. Packet switching copies that idea—small parts travel quickly and independently.

Packet switching lets many users share the same wires. Each labeled chunk slips between others, so no one hogs the link. If one path fails, packets reroute and the conversation survives. That flexibility keeps today’s Internet resilient.

The packet pioneers: baran and davies

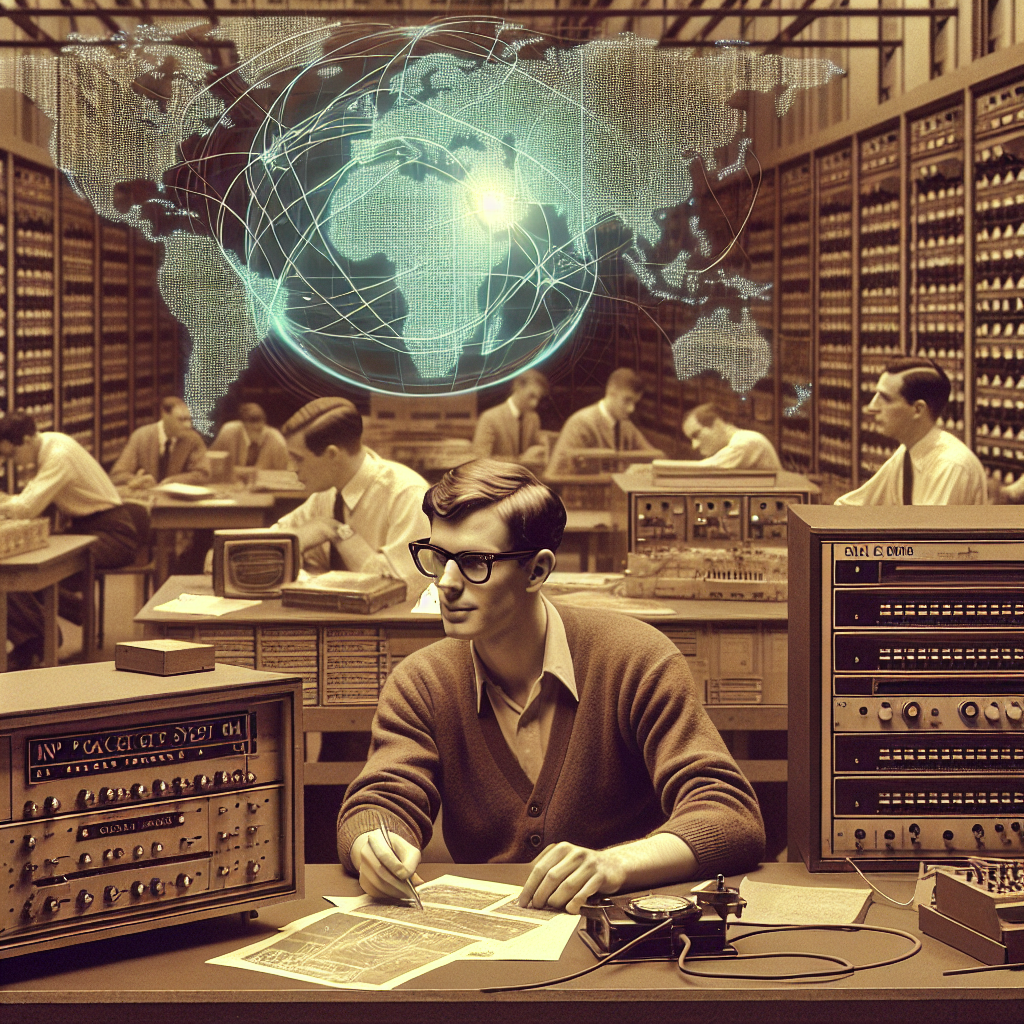

In the 1960s, Paul Baran at RAND asked how messages could survive wartime damage. He proposed chunks that knew the destination but not the path, letting packets weave through any working link. His model promised a self-healing network.

Across the Atlantic, Donald Davies coined the term “packet” and built a live system. He proved you could chop, send, and reassemble data cheaply and fast. Together, these thinkers inspired ARPANET and, eventually, the modern Internet.

Protocols: the rules of the road

Protocols act like traffic laws, guiding every packet so networks avoid chaos. Rules tell devices when to send, wait, or retry, making global cooperation possible.

IP writes each packet’s address. TCP checks arrival, orders packets, and requests missing ones—similar to tracked mail. Lighter protocols handle quick tasks like pings or address assignments. Shared standards mean any computer, router, or phone can interoperate despite age or brand.