Power, Pages, and Parchment: Women Who Wrote History

Setting the Stage: Who Gets to Write?

Imagine learning to read with your family in a sunlit room. Now travel back 700 years, where books were rare and reading felt like holding a secret key few possessed. That key went mostly to men—priests, monks, and noble sons—while most girls faced chores instead of classrooms.

Social class added another lock. Noble children found tutors, yet boys still stood first in line. Girls might pick up just enough letters to manage accounts or pen a polite note. Farmers’ daughters rarely saw a school at all.

More Gates to Literacy

Religion shaped access. Monasteries and convents taught reading, but only future monks or nuns could enter. Geography mattered, too. In Heian Japan, noblewomen enjoyed room for study, while much of Europe urged women to stay silent and obedient. Even literate women met a final barrier: official records, penned by men, ignored them.

Yet many women refused to stay quiet. Their determination—and a bit of luck—let their words slip through history’s cracks.

Hildegard of Bingen: Visions and Voices

Hildegard was born in 1098, sent to a convent, and rose to lead it. She wrote letters to kings and popes, described her visions in Scivias, and crafted vibrant manuscripts. One daring line jolted her era: “Woman may be made from man, but no man can be made without a woman.”

Hildegard’s Music and Reach

More than 70 of her chants survive, making her the earliest named female composer in Western music. Picture soaring melodies echoing through a stone chapel. Because she led a convent, Hildegard gathered skilled women, studied herbs, and sent her books across Europe—preserving them for 900 years.

Murasaki Shikibu and The Tale of Genji

Heian-period Japan valued refined art. Men drafted official texts in Chinese, while women shaped stories in Japanese kana. Murasaki, daughter of a scholar, seized this opening and penned The Tale of Genji, often called the world’s first novel.

Layers of Life and Longing

Her novel follows a fictional prince through love and loss, capturing quiet moments—the angle of light on silk, a hidden message on a fan. Murasaki’s careful observation lets modern readers feel the pulse of a court a thousand years gone.

Women Troubadours and Sacred Song

In 12th-century southern France, trobairitz wrote lyrics on love and honor. Beatriz de Dia confessed, “I must sing of what I do not want to say.” Society rarely let them perform publicly, yet their melodies drifted through courts and lingered in memory.

Voices Behind Cloistered Walls

Inside convents, women copied plainchant and composed new masses. Group singing shaped spiritual life. While many names vanished, their music lives on in fragile manuscripts, proving shared song can outlast silence.

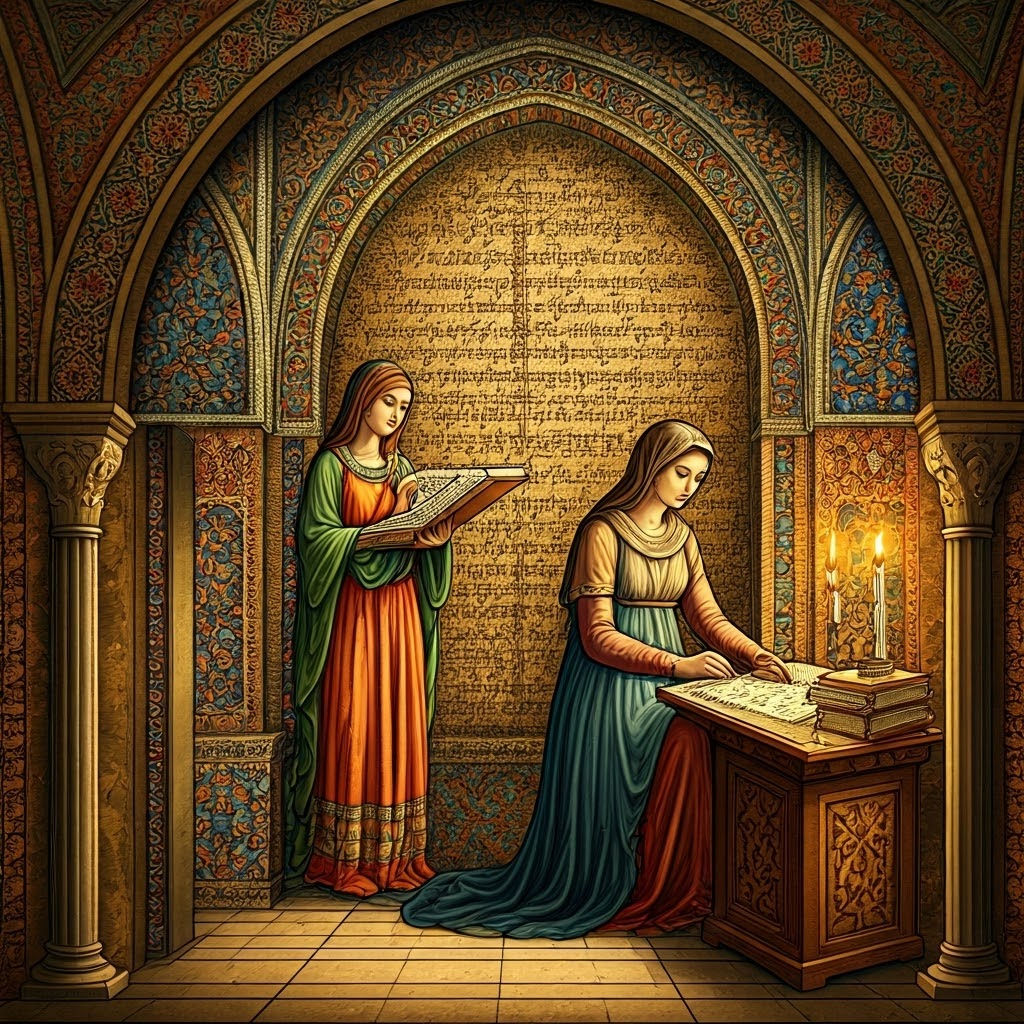

Keeping the Record: Chroniclers and Scribes

Historians crave firsthand voices. Noblewomen kept prayer books with notes, penned lively letters, and recorded local events. In the 15th century, Christine de Pizan defended women’s worth in The Book of the City of Ladies, challenging male scholars with clear logic.

Broader Horizons

Across cultures, women joined the scholarly conversation. Fatima al-Samarqandi helped interpret Islamic law, and Anna Komnene chronicled her father’s reign, writing, “Who but I could know the true heart of the story?” Such records bridge modern readers to everyday medieval life.

Why These Stories Matter

The work of women writers reshapes history’s focus from kings and battles to human experience—hopes, fears, and joys. When we read Hildegard’s letters or Murasaki’s prose, their voices travel centuries to meet us. By seeking missing voices, we hear the past more fully and imagine richer futures.