Seeing the Invisible: The Many Colors of Light

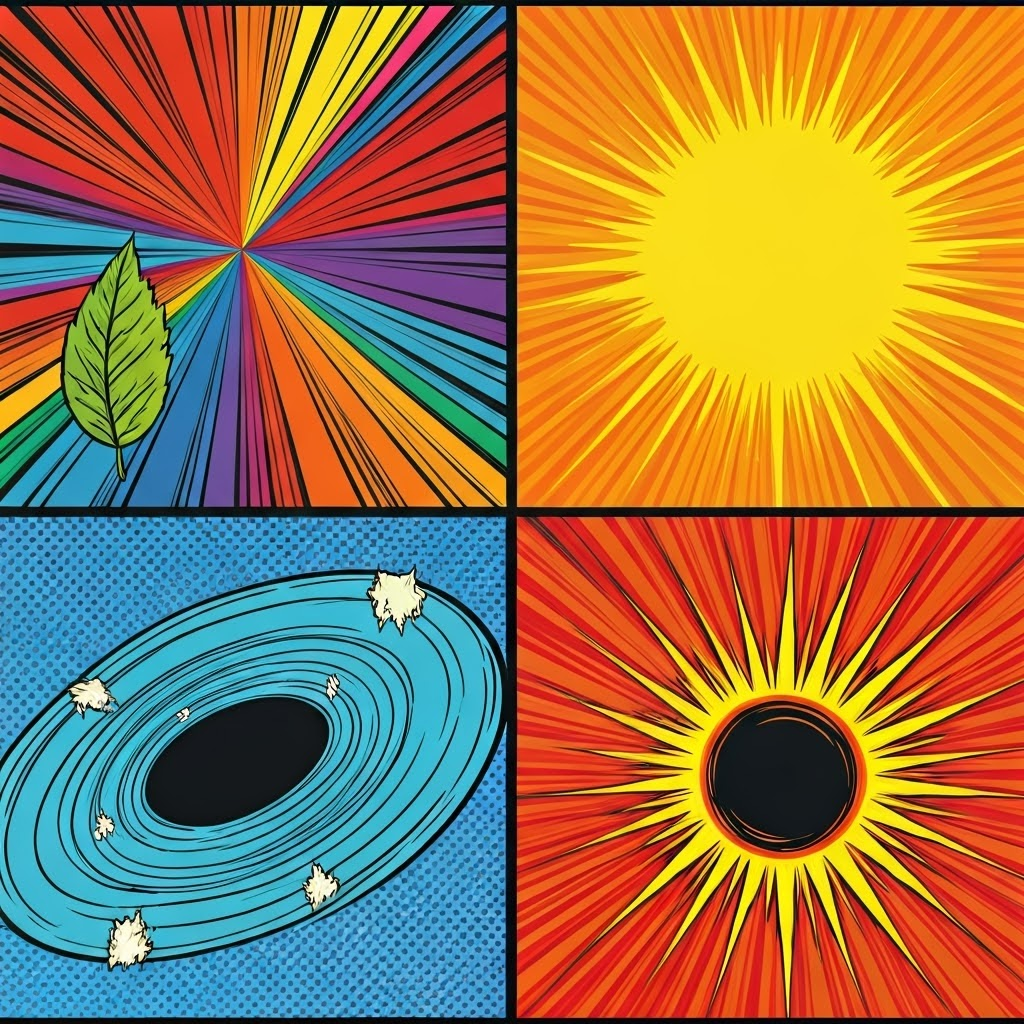

Light is energy that moves in waves, yet it also shows up as tiny photons. This odd mix—wave and particle—lets astronomers read distant starlight.

What Light Really Is

Think of gentle sea waves, then picture single stones hitting water. Those images match light’s two faces. This duality is key to how telescopes turn faint glimmers into rich data.

A bit of history: Newton and the secret colors

A wavelength is the distance between wave peaks. Shorter waves carry more energy—that is why X-rays pierce skin while radio waves do not. Newton’s prism showed white light hides many colors, inspiring today’s spectral studies of stars.

The Full Spectrum: Beyond What We See

Radio waves have football-field lengths. Huge dishes catch these quiet signals, revealing cold gas, spinning pulsars, and the galaxy’s skeleton.

Infrared waves are shorter than radio yet still unseen. You feel them as heat. Space telescopes like Webb expose baby stars wrapped in dusty cocoons.

Infrared waves are shorter than radio yet still unseen. You feel them as heat. Space telescopes like Webb expose baby stars wrapped in dusty cocoons.

Why can’t we see all this with our eyes?

Earth’s air blocks most invisible light. While that shield keeps us safe, astronomers need specialized instruments—and often spacecraft—to view the full show.

Visible light paints sunsets and guided early astronomy. Ultraviolet unveils hot, young stars. X-rays track gas spiraling into black holes, while gamma rays spotlight the universe’s most violent blasts.

Visible light paints sunsets and guided early astronomy. Ultraviolet unveils hot, young stars. X-rays track gas spiraling into black holes, while gamma rays spotlight the universe’s most violent blasts.

Why Astronomers Love Invisible Light

Each band fills gaps left by the others. Radio maps hydrogen clouds. Infrared cuts through dust. Together they build a layered, complete picture of galaxies.

Ultraviolet pinpoints energetic nurseries. X-ray and gamma-ray observatories catch black holes feasting and stars exploding. Blending clues from the whole spectrum tells a star’s real story.

Ultraviolet pinpoints energetic nurseries. X-ray and gamma-ray observatories catch black holes feasting and stars exploding. Blending clues from the whole spectrum tells a star’s real story.

Curiosity grows when you look beyond sight. The universe beams countless messages—learn to listen past what your eyes reveal.