Setting Sail: The World Before Darwin

Old Beliefs and New Questions

Two hundred years ago, most people believed every species was fixed. A horse stayed a horse, an oak stayed an oak, and humans stood apart. This idea, called fixity of species, felt safe because it matched church teachings.

The world appeared orderly. Each creature seemed to occupy a perfect place in creation. Nothing bizarre—like a cabbage slowly turning into a sunflower—was expected.

Fossils soon cracked that calm picture. Giant bones and seashells far from any coast looked out of place. Scholars argued: tricks of stone or traces of a biblical flood? Some whispered a forbidden word—extinction.

French anatomist Georges Cuvier piled up evidence in the quarries below Paris. Layer after layer revealed vanished worlds. The air felt tense, like thunder before a storm—questions boomed, answers lagged.

Lamarck, Lyell, and the Seeds of Change

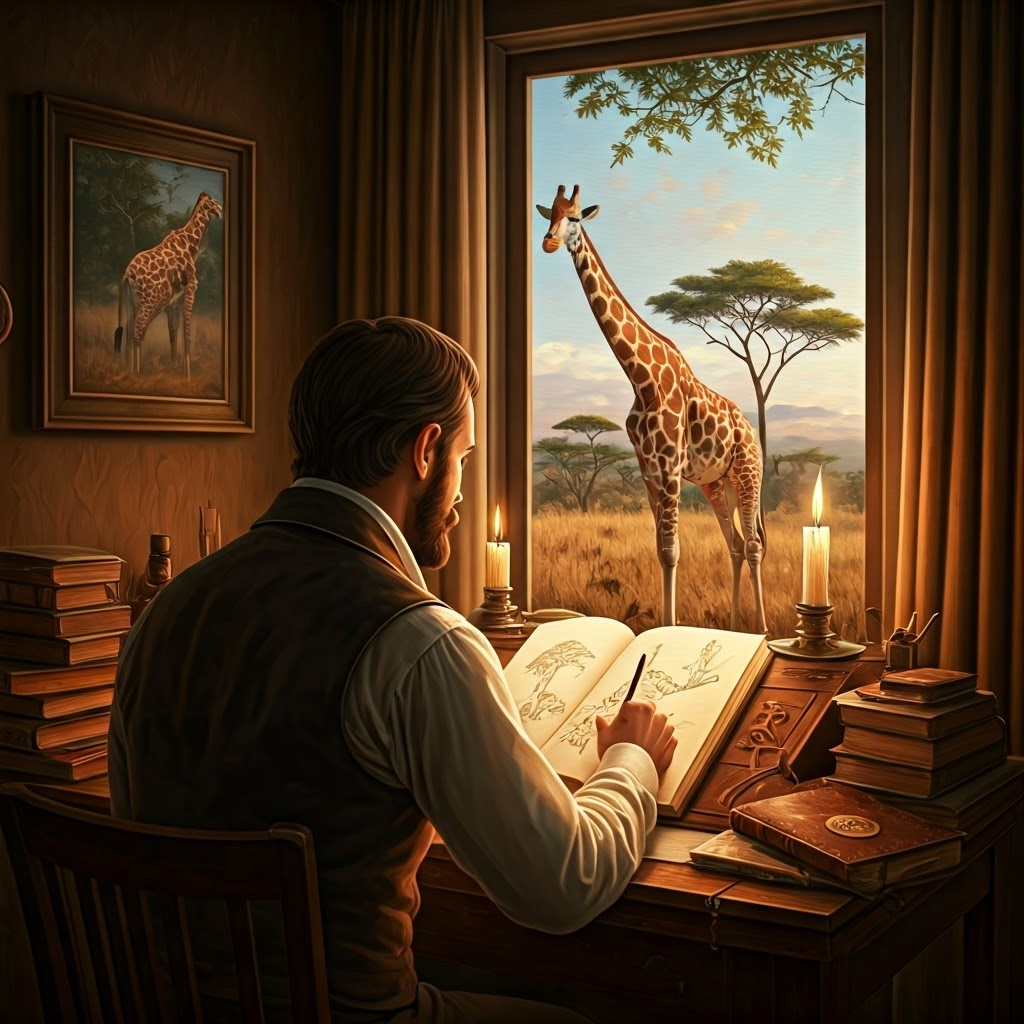

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck suggested that species could shift over time. He pictured giraffes stretching for leaves and passing the added reach to their young. His bold claim about the inheritance of acquired traits met doubt, yet it opened minds to gradual change.

While zoologists argued, Charles Lyell watched rivers cut valleys and waves grind cliffs. He called this slow, steady process uniformitarianism. If gentle forces could shape mountains over eons, maybe small shifts could sculpt life as well.

Lyell’s long timeline rewrote Earth’s history. Time stretched, patience grew, and naturalists now saw change everywhere, not just in rocks.

Curiosity on the Edge of Discovery

The early 1800s surged with exploration. Ships hauled back crates of shells, beetles, and pressed plants. London’s museums buzzed as collectors traded specimens and ideas.

Visitors noticed patterns. Australia held creatures found nowhere else. Elephant bones resembled—but did not match—mammoths. Each cabinet hinted at rules no one could yet state.

Naturalists sensed Lamarck’s and Lyell’s hints but still lacked a unifying answer. It felt like holding a puzzle with half the pieces. As ships sailed farther, journals filled with oddities, and a bold idea hovered on the horizon—ready to redraw the map of life.