Lost, Found, and Carried Forward: How Ancient Ideas Survived

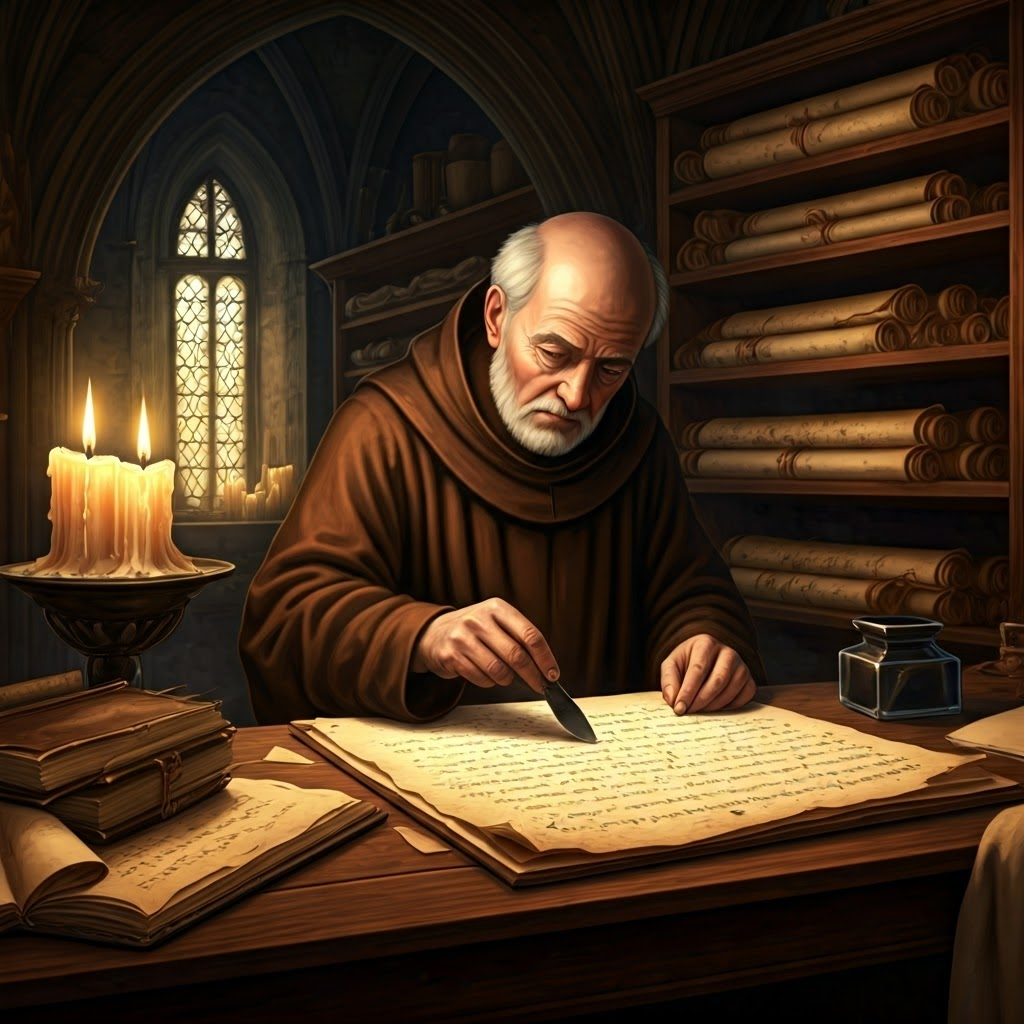

Guardians of the Past: Monks, Manuscripts, and Memory

If you hold a printed copy of Homer or Aristotle today, you owe that gift to centuries of patient monastic scribes. They copied each letter by hand, often in cold rooms lit only by candles. Their quiet labor kept knowledge alive for readers they would never meet.

Few books came through unscathed. Lucretius’s poem On the Nature of Things almost vanished; only two copies surfaced in the fifteenth century. Of more than 120 Sophocles plays, just seven have survived because monks chose to recopy them. Each selection reshaped the cultural record.

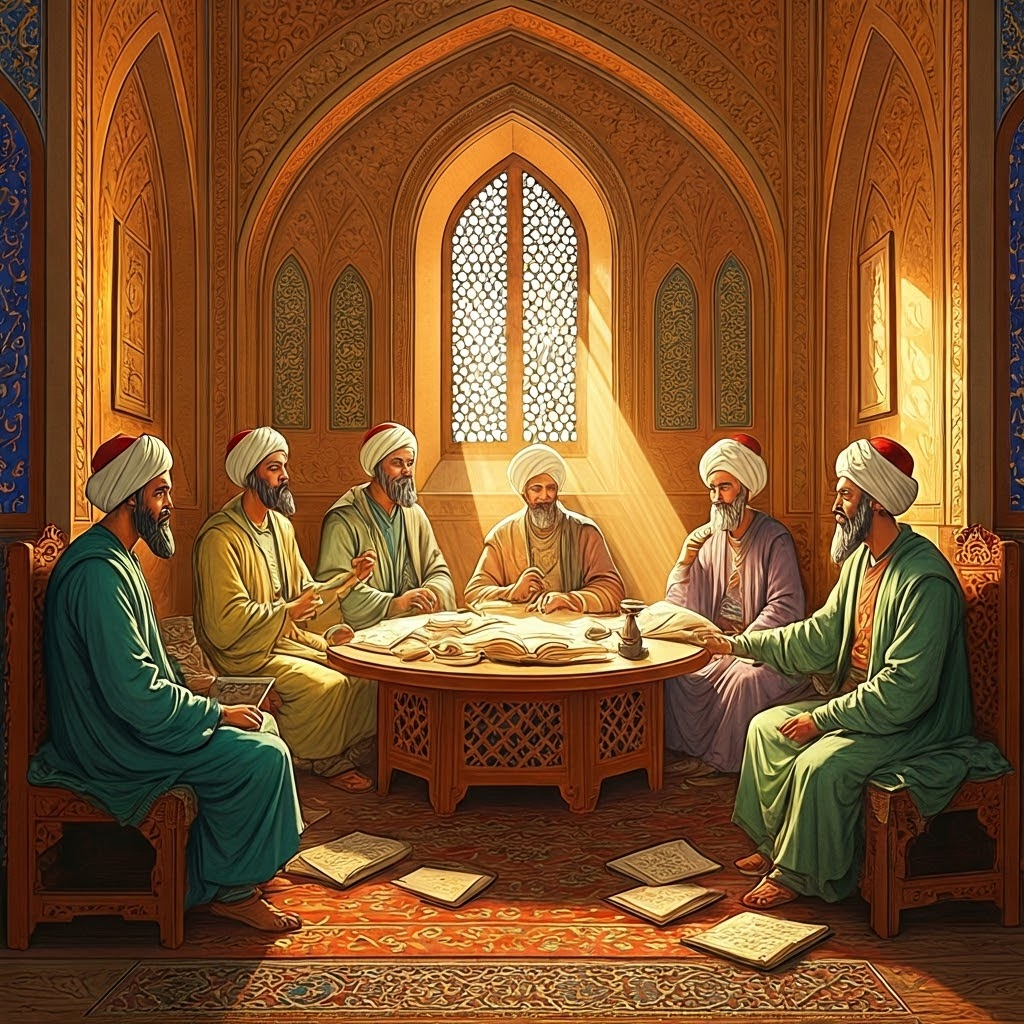

Baghdad’s Golden Hour: Translation and Transformation

Medieval Baghdad shone as a beacon of learning. During the eighth and ninth centuries, Abbasid caliphs gathered texts from Greece and Rome. At the House of Wisdom, translators turned these works into Arabic and refined their ideas.

Hunayn ibn Ishaq led teams that clarified Galen and Aristotle. Thinkers such as al-Kindi and al-Farabi blended Greek philosophy with Islamic thought, creating hybrid systems. When Europe later reconnected with the East, it met Greek ideas filtered through Arabic minds.

Aristotle’s Politics returned to Europe wrapped in new glosses and a few errors, yet its core still guided debate. Baghdad’s translators did more than save the ancient world—they globalized it.

Renaissance Rediscoveries: Petrarch, Humanists, and the Printing Press

In fourteenth-century Italy, Petrarch hunted forgotten texts. His find of Cicero’s letters in 1333 electrified humanists who saw ancient works as guides for clear thinking and elegant prose.

Gutenberg’s printing press, invented around 1450, changed everything. Books could now reach hundreds of readers quickly and cheaply. Early printers cross-checked copies, reducing errors and anchoring the modern canon of classics.

Many works remain lost, known only through fragments or later references. Yet from monks to Baghdad scholars to Renaissance printers, countless hands chose what mattered. Their choices still shape what we can read—and question—today.