Steam, Sparks, and the Age of Change

Factories, Fire, and the Race for Power

Step back to England in 1750. Muddy roads wind past small workshops powered by muscle and waterwheels. Nights glow faintly from candles. Life moves slowly—yet change is gathering just over the horizon. Muscle-driven work is about to meet something far stronger.

Waterwheels stall when rivers freeze or dry. People stay close to home because distance costs effort. Once the sun sets, work ends. Then steam engines roar to life, and the quiet countryside turns loud, bright, and fast. Cities will soon swell around mines and mills. Coal fuels the leap.

Factories rise almost overnight, filling the air with clatter and smoke. Families leave farms for wages, sharing long shifts beside spinning machines. Jobs promise both hope and danger. The drive for progress reshapes every routine.

The steam engine turns heat into force. It drains mines, powers looms, and soon propels trains and ships. Inventors race to improve power, cost, and reliability. Patent books overflow with sketches. Control over energy becomes the era’s obsession.

James Watt and the Engine That Could

Scottish instrument maker James Watt studies a faulty engine and sees waste. Each cycle reheats cooled parts, burning extra coal. His sharp eye turns a simple repair into a world-changing insight. Efficiency becomes his guiding word.

Watt adds a separate condenser—like a steam refrigerator—so only one section cools. Fuel use drops, power soars. Engines now serve factories, pumps, and ships at lower cost. A modest tweak unleashes vast industrial growth. Fuel-saving design proves priceless.

Watt keeps refining. His spinning governor automatically steadies engine speed, making steam power safer. With reliable engines, factories can operate anywhere—no river required. Cities thicken, smoke darkens skies, and daily life now ticks to the rhythm of machinery.

Sadi Carnot and the Puzzle of Heat

As steam spreads, scientists ask: what is heat? Many imagine an invisible fluid called caloric. French officer Sadi Carnot challenges this view in 1824, seeking the maximum possible engine performance. Curiosity pushes him forward.

Carnot pictures heat falling from hot to cold like water over a wheel. Some energy always escapes as warmth; no machine can convert it all to work. His ideal Carnot engine frames the new science of thermodynamics.

Others build on Carnot’s ideas. Clausius and Kelvin craft the laws of thermodynamics, revealing that energy cannot be created or destroyed. Their work influences engines, weather, chemistry, and even cosmology. Energy-law thinking spreads everywhere.

The World Watches: Public Demos and World’s Fairs

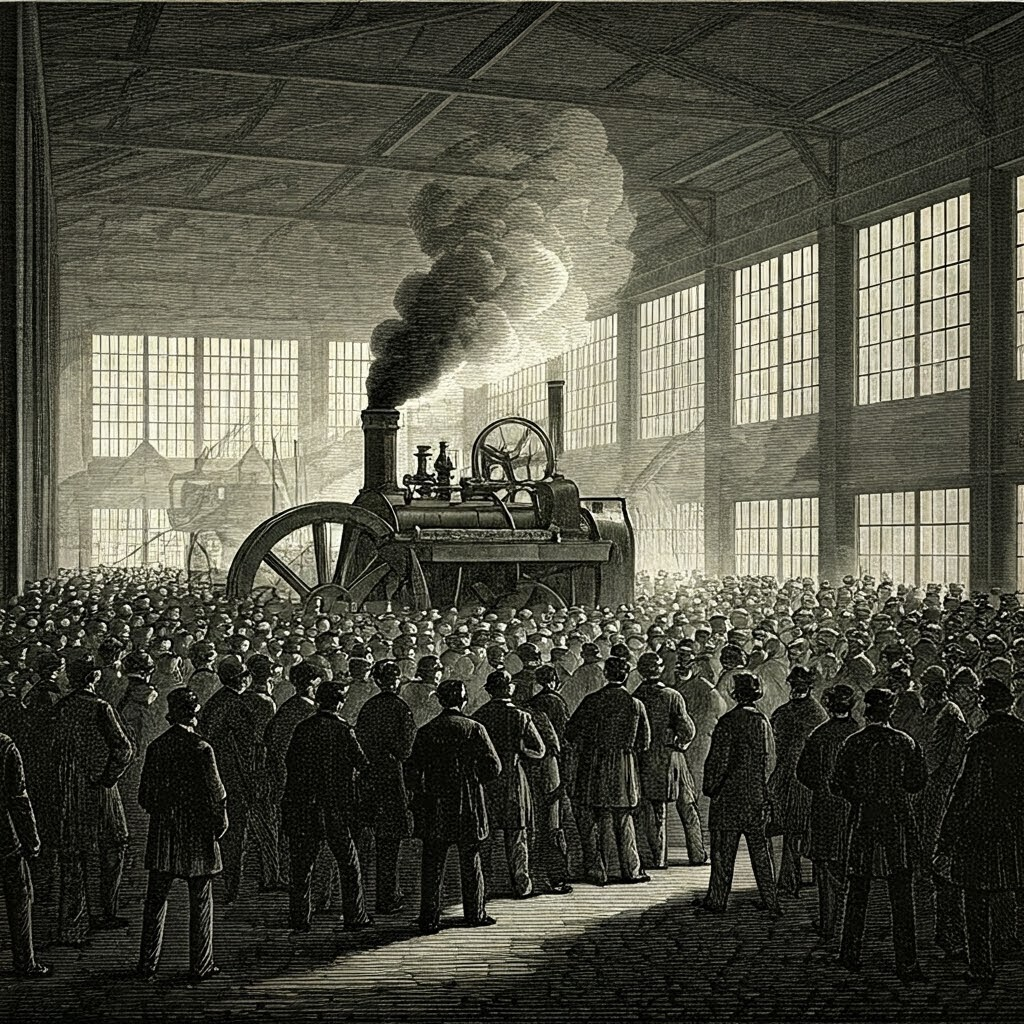

Industrial wonders become public spectacles. Factory owners invite crowds to see engines breathe fire and spin steel. Newspapers describe roaring machines as theater. Amazed visitors feel the floor shake and the heat rise. Spectacle sells progress.

At the 1851 Great Exhibition, Queen Victoria strolls beneath Crystal Palace glass, admiring engines from every nation. Travelers share stories of speed and smoke. The impossible now feels ordinary, inspiring fresh invention. Innovation becomes a social event.

Even those far from factories sense the change. Goods grow cheaper, travel quickens, and power feels purchasable. Excitement mixes with anxiety as steam sets the stage for electricity, magnetism, and a global web of energy yet to come.