Breaking the Mold: Work, Invention, and Everyday Defiance

Women in the Industrial Era grabbed new chances to earn wages, invent tools, and travel freely. Their everyday choices—working long shifts, filing patents, or riding bicycles—quietly shook old rules and opened paths to vote, study, and secure fairer workplaces. Change began in small moments.

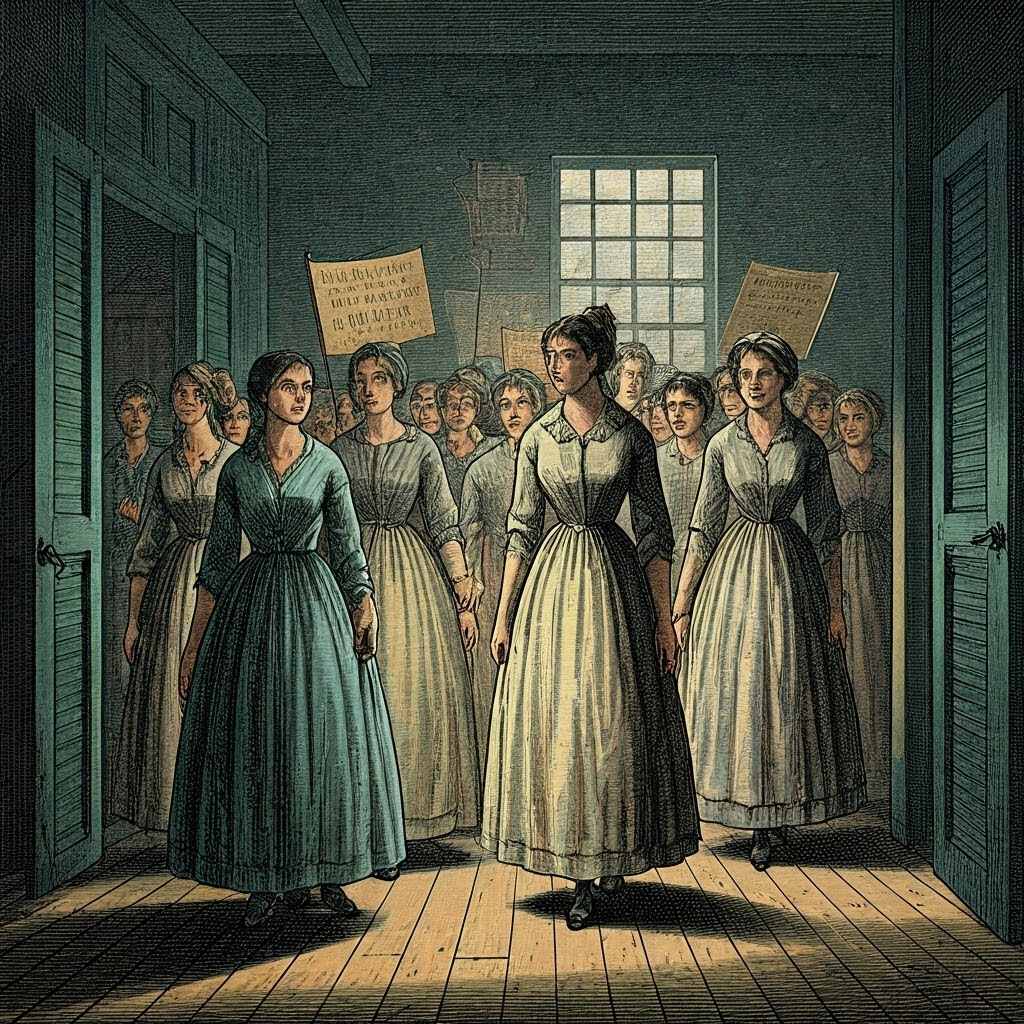

Factories, Unions, and the First Shifts

Factories needed hands, and women—often teens—answered. Options had been farm chores or domestic service. Steam-powered looms and metal presses now paid modest wages and offered a taste of independence.

Shifts ran twelve to sixteen hours. Cotton dust clouded lungs, chemicals stung skin, and loud gears mangled fingers. Owners rarely fixed hazards, so accidents remained common.

Out of this grind, early strikes flared. In the 1830s, Lowell mill workers left their looms to protest wage cuts and fees. They faced firing yet printed a newspaper and pressed for a ten-hour day—proof that strikes could work.

Across the Atlantic, British match girls walked out over deadly white phosphorus. Each partial win chipped at the idea that women should simply accept any job.

Long hours forged tight bonds. Side by side, women shared skills, wrote leaflets, and planned actions. This daily cooperation built lasting solidarity that reached far beyond pay disputes.

Inventors in Aprons and Overalls

Inventing was never just for men in labs. Hundreds of women filed patents that eased daily life. Massachusetts mill worker Margaret Knight created a flat-bottomed paper-bag machine. When a man stole her idea, she sued and won, proving ingenuity in court.

Mary Anderson designed the first windshield wiper; at first, automakers ignored her. Josephine Cochrane built a pressure-based dishwasher to stop servants from chipping china. Hotels soon bought dozens, turning her surname into a brand.

Patents cost money and needed male witnesses. Often applications listed a woman only as “Mrs.” plus her husband’s initials. Even so, inventions like fire escapes and medical syringes spread, showing that credit mattered for recognition as much as profit.

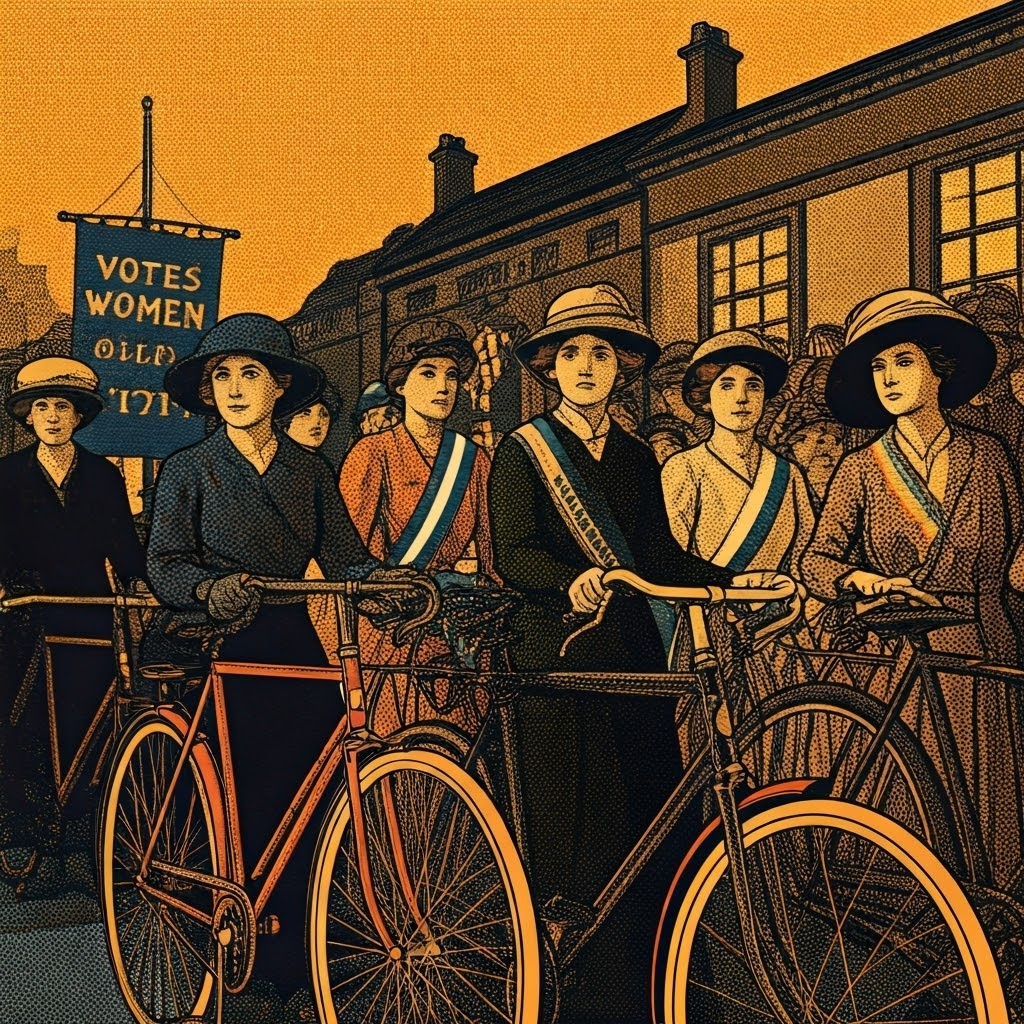

Bloomers, Bicycles, and the Freedom to Move

Clothing could liberate, too. Amelia Bloomer promoted loose trousers under shorter skirts. Lighter fabric meant fewer snags in machinery and easier walking—early steps toward dress reform.

The bicycle became a “freedom machine.” Women pedaled miles without chaperones, bought their own tickets, and met friends on their schedule. Critics warned of “bicycle face,” yet riders kept going, linking wheels to wider mobility rights.

Everyday Acts and the Ripple Effect

Change often starts quietly. Each woman who rejected unpaid overtime, patented a gadget, or rode a bike nudged society forward. The Industrial Era multiplied ways to prove ability and demand respect—laying groundwork for future rights at the ballot box, campus gate, and office door.