The Trail Begins: Tracing the Human Spark

A World Transformed: The Industrial Revolution

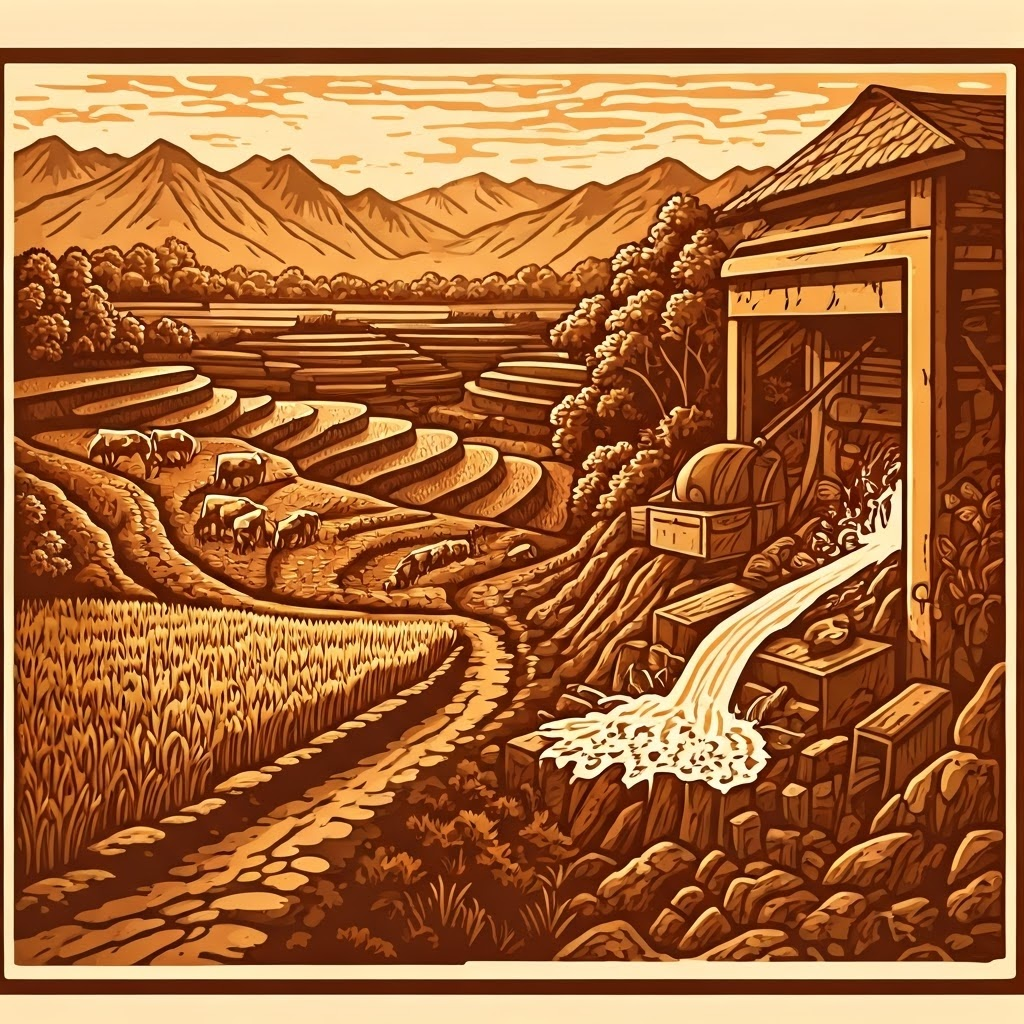

Life in the early 1700s moved slowly and stayed local. People relied on muscle, wind, water, and wood for energy. Nights glowed only from candles or small fires. Most work centered on farming or small trades, and news rarely traveled far from home.

Then the Industrial Revolution swept through Britain around 1760. Coal became the main fuel. Steam engines powered textile mills, trains, and ships. Cities expanded quickly, and black smoke turned into a familiar sight.

Within a few generations, humans shifted from nearby natural energy to ancient underground carbon. This change built modern life—cars, planes, and computers—but it also released new gases that linger in the air and warm the planet.

Greenhouse Gases: The Basics

Picture Earth wrapped in a fuzzy blanket. The blanket lets sunlight in yet slows heat escaping. Tiny amounts of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide weave this blanket and keep the planet comfortably warm.

Sunlight passes through easily. When warmed ground sends heat back as infrared energy, these gases trap part of it. This natural greenhouse effect prevents Earth from becoming an ice ball, but too many gases thicken the blanket and raise temperatures.

CO₂ dominates because burning coal, oil, and gas releases ancient carbon. Methane is rarer yet traps more heat per molecule; it comes from livestock, rice fields, leaky wells, and garbage. Nitrous oxide arises mainly from fertilizers and certain factories.

You can’t see or smell these gases, but their impact is huge. Scientists track CO₂ at just over 400 parts per million. Even such tiny concentrations matter because they spread across the entire atmosphere.

Emissions by the Numbers

Burning fossil fuels for energy makes up over three-quarters of CO₂ and roughly two-thirds of all greenhouse gases. Every light switched on or phone charged likely depends on fuel-burning power plants.

Transport follows closely. A typical U.S. car emits about 4.6 tons of CO₂ yearly. Multiplied by millions of vehicles, this becomes a major slice of global emissions.

Agriculture adds more gases. Cows and sheep burp methane; rice paddies emit methane; fertilizers release nitrous oxide. Farming feeds us yet also changes the atmosphere.

Making cement and steel releases CO₂ during chemical reactions, independent of fuel use. Cement alone contributes about 8 % of global CO₂ emissions.

Emissions stayed tiny until the 1800s, climbed by 1900, and exploded after World War II. Humans now add carbon faster than any known natural process, leaving a clear mark that shapes the story ahead.