Vibrations: Where Sound Begins

The Secret Life of Vibrations

Sound enters our world through vibrations that move back and forth, often unnoticed until we pay attention. Tap a table with one finger and you set the wood shaking, even if your eyes miss it.

A vibration repeats itself—swinging one way, then the other—like a child on a swing or a plucked guitar string. That steady back-and-forth motion starts every sound you hear.

When hands clap, they squeeze the air between them. Nearby air particles crowd together, then spread apart, passing the push along. Each tiny bump moves the vibration forward.

Musical instruments use the same trick. Press a piano key and a string starts to move. Strike a drum and the head wiggles up and down. Even a kettle whistle comes from metal vibrating as steam escapes.

Your ears catch these small wobbles. Air, water, and solids can all carry them, guiding vibrations from the source to you. That’s why the sound of footsteps reveals a friend nearby even before you look.

Waves on the Move

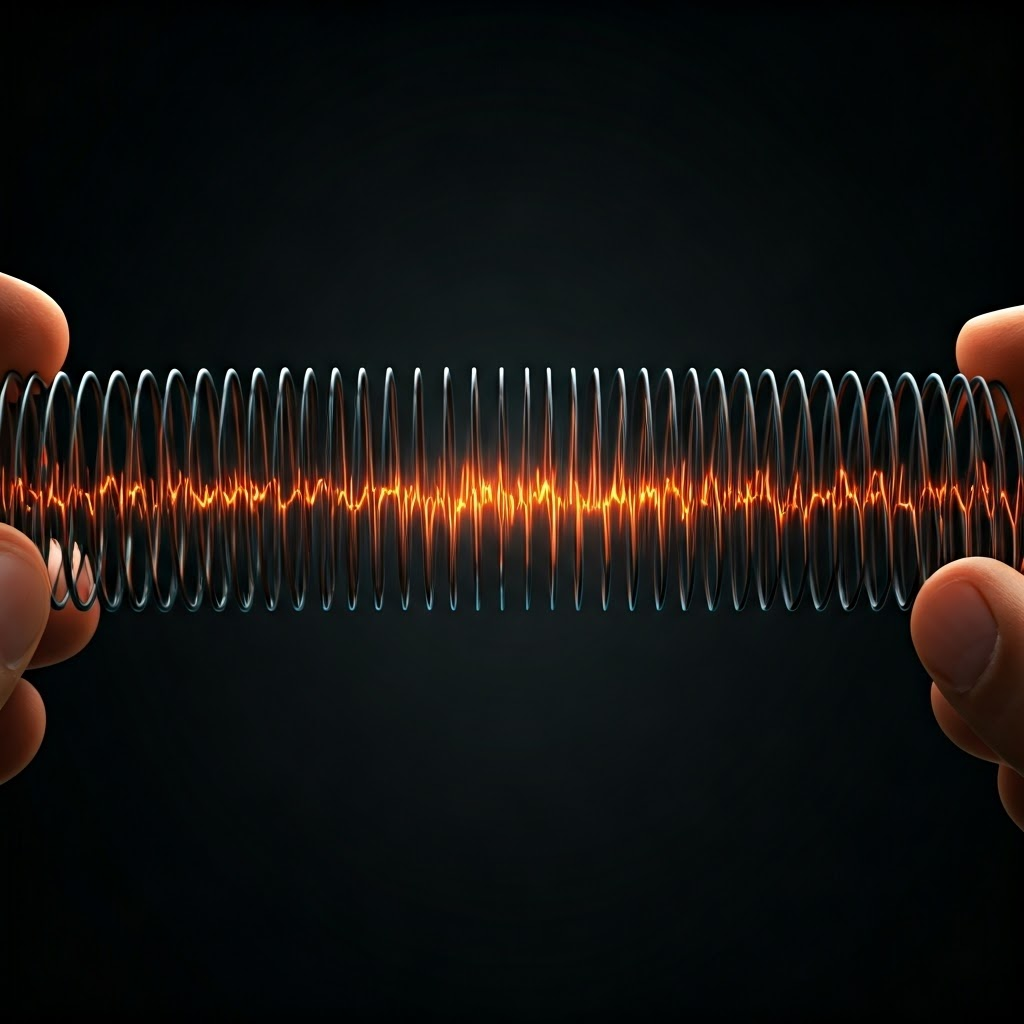

Vibrations become sound only when they travel. They do this by forming waves through a material—usually air. A mechanical wave appears when a vibration moves through matter. Shake one end of a slinky and a wave races along while each coil simply moves in place.

Sound needs a medium because its waves push and pull particles. Light is different: as an electromagnetic wave, it moves through empty space. You can see the Sun from space but cannot hear an explosion there—no particles, no sound.

Try this: rest your ear on a table and tap the other side. The tap sounds clearer than through air because solids carry sound better. Water is also efficient; whales sing across oceans. In air sound travels about 343 m/s, in water 1 500 m/s, and in steel even faster.

Pitch, Frequency, and Musical Notes

A kettle’s high whistle and a drum’s low boom differ in frequency—how many times a vibration repeats each second, measured in hertz (Hz).

A violin string that vibrates 400 times per second sounds higher than a cello string moving 100 times per second. Faster vibration means higher pitch; slower means lower. On a piano, notes to the right vibrate faster than those on the left.

Young ears detect roughly 20 Hz to 20 000 Hz. The standard musical “A” above middle C rings at 440 Hz. A passing siren changes pitch because motion shifts the perceived frequency—a topic for another time.

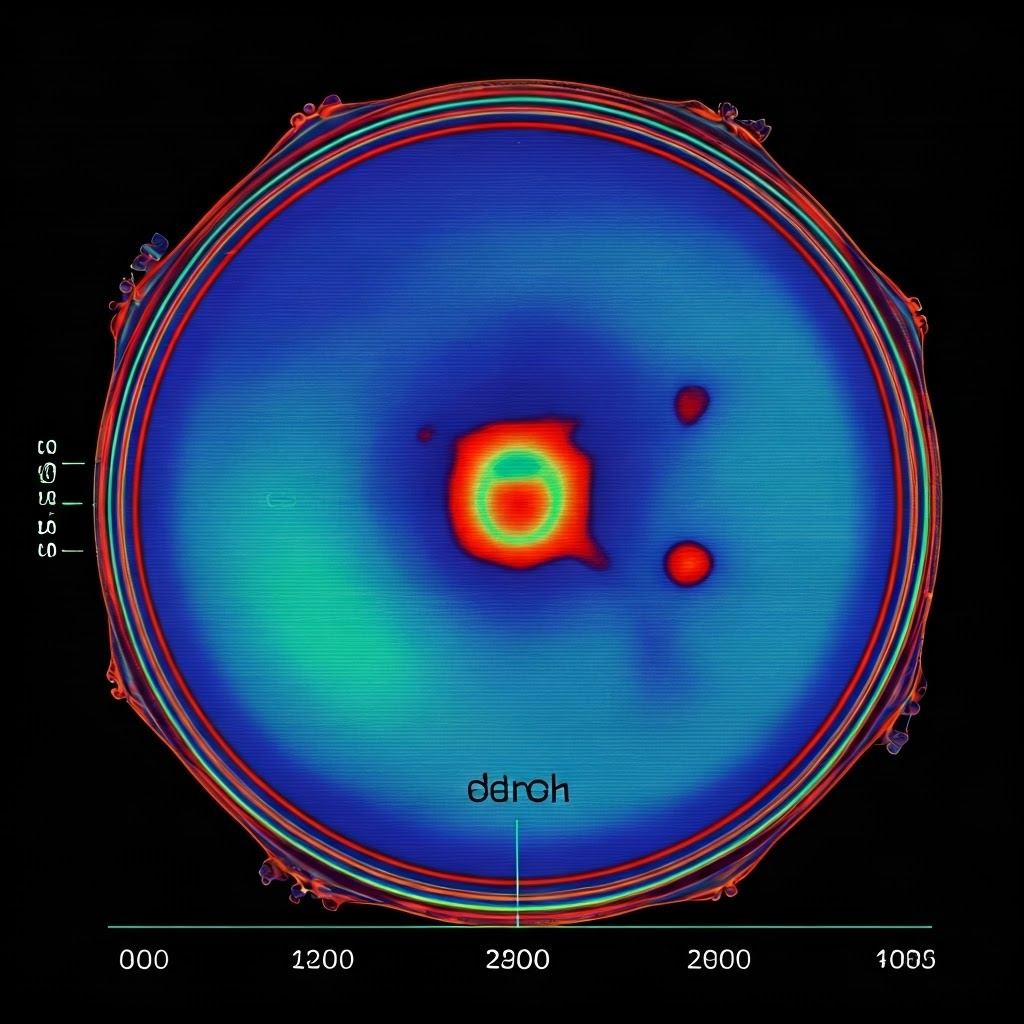

Amplitude and Loudness: Why Some Sounds Shout

Amplitude tells how big each vibration is. A string that moves a lot per cycle has large amplitude; one that barely shifts has small amplitude.

Larger amplitude feels louder. Whispering makes low-amplitude waves; shouting makes high-amplitude waves that travel farther. Tap a drum lightly and it barely moves, producing quiet ripples. Strike it hard and the drumhead swings wide, pushing more air and sounding loud.