Fire in the Cane Fields: How Saint-Domingue Became a Powder Keg

Sugar, Coffee, and Chains

On the western half of today’s Haiti you could smell sugar every morning. Saint-Domingue’s plantation economy made it the richest colony on Earth in the late 1700s. Half the world’s coffee and about 40 % of its sugar left these fields—wealth built on the labor of enslaved people.

Sugar, Coffee, and Chains

Thousands lived jammed onto plantations where cane towered above them. Work started before sunrise and dragged past dark, six or more days a week. Overseers watched with whips ready. Injuries mounted, food spoiled, and disease spread. The average newcomer from Africa survived less than ten years, while ships full of sugar made French owners richer.

Sugar, Coffee, and Chains

Violence held the system together. The Code Noir set rules on paper, yet cruelty ruled in practice—beatings, mutilation, and public punishments. Historian C. L. R. James called Saint-Domingue a “factory in the field,” with people as machines. Even then, the enslaved never stopped their resistance through escape, sabotage, and quiet defiance.

A Society on Edge

The colony’s social pyramid cut everyone beneath it. Grand blancs owned vast estates and hundreds of workers. Petits blancs—shopkeepers, sailors, artisans—often lived poorer than some free Black residents. Free people of color could own land or even slaves yet faced legal walls because of their ancestry. Status defined daily life.

A Society on Edge

Nearly half a million enslaved Africans formed the base of this fragile order. Petits blancs feared free people of color as rivals. Planters feared rebellions. Free people of color bristled at discrimination while paying taxes and serving in militias. Enslaved workers watched every crack in the system for chances to act.

Revolution in the Air

News of the 1789 French Revolution hit the colony like a storm. Liberty, equality, and fraternity sounded thrilling or terrifying, depending on who listened. White planters feared losing power. Petits blancs demanded rights, often against free people of color, whom they viewed as dangerous competitors.

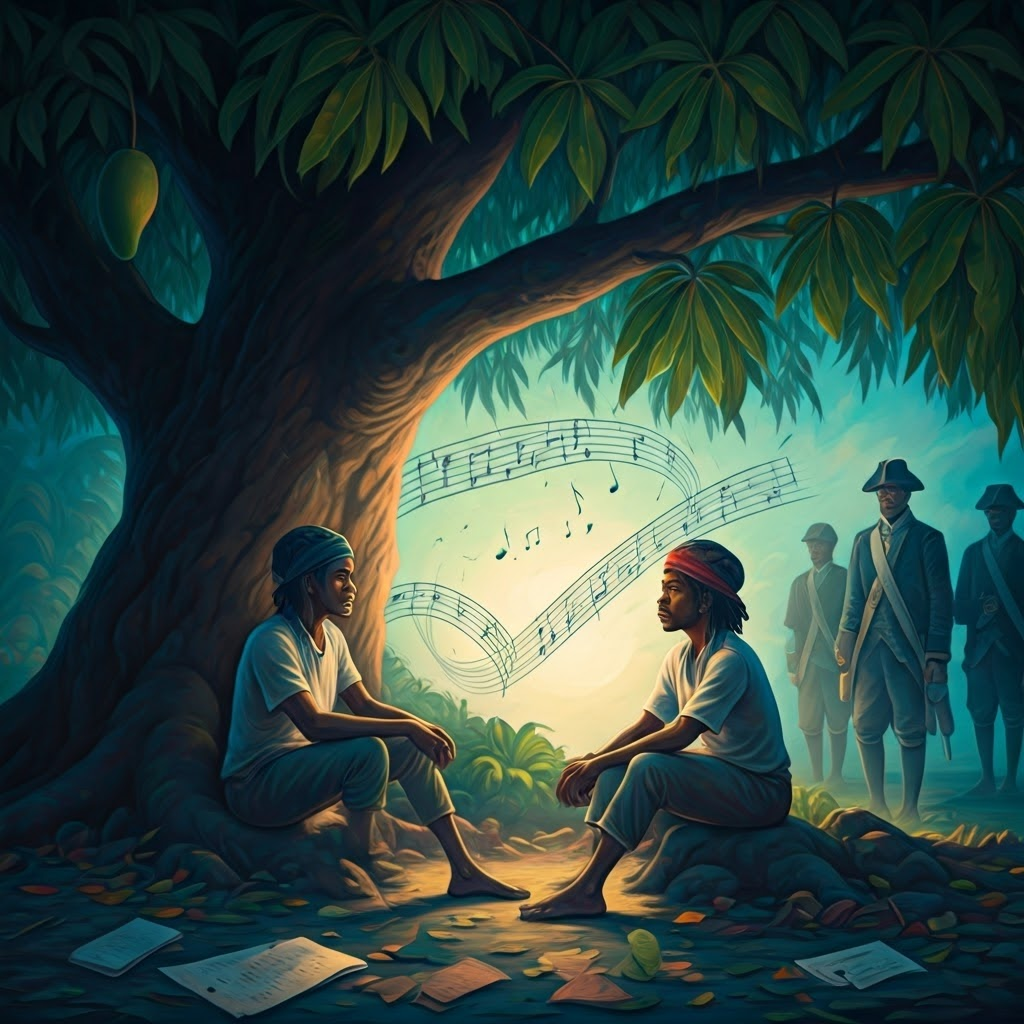

Revolution in the Air

For the enslaved, revolutionary ideas promised freedom. They met in secret, spread rumors, and sang coded songs. Maroons moved boldly through the hills. Colonial authorities banned publications, censored mail, and tightened punishment, yet the ideas kept spreading—an electric hope no law could cage.

Revolution in the Air

By 1791, tension felt like dry tinder. When the first fires tore through the cane, the struggle was already lit—by greed, cruelty, and the fierce belief that Saint-Domingue could remake the world.