How Industry Crossed Borders: Secrets, Smugglers, and New Players

Picture an early-1800s Britain racing ahead, its mills humming and profits soaring while the rest of the world strains to keep up.

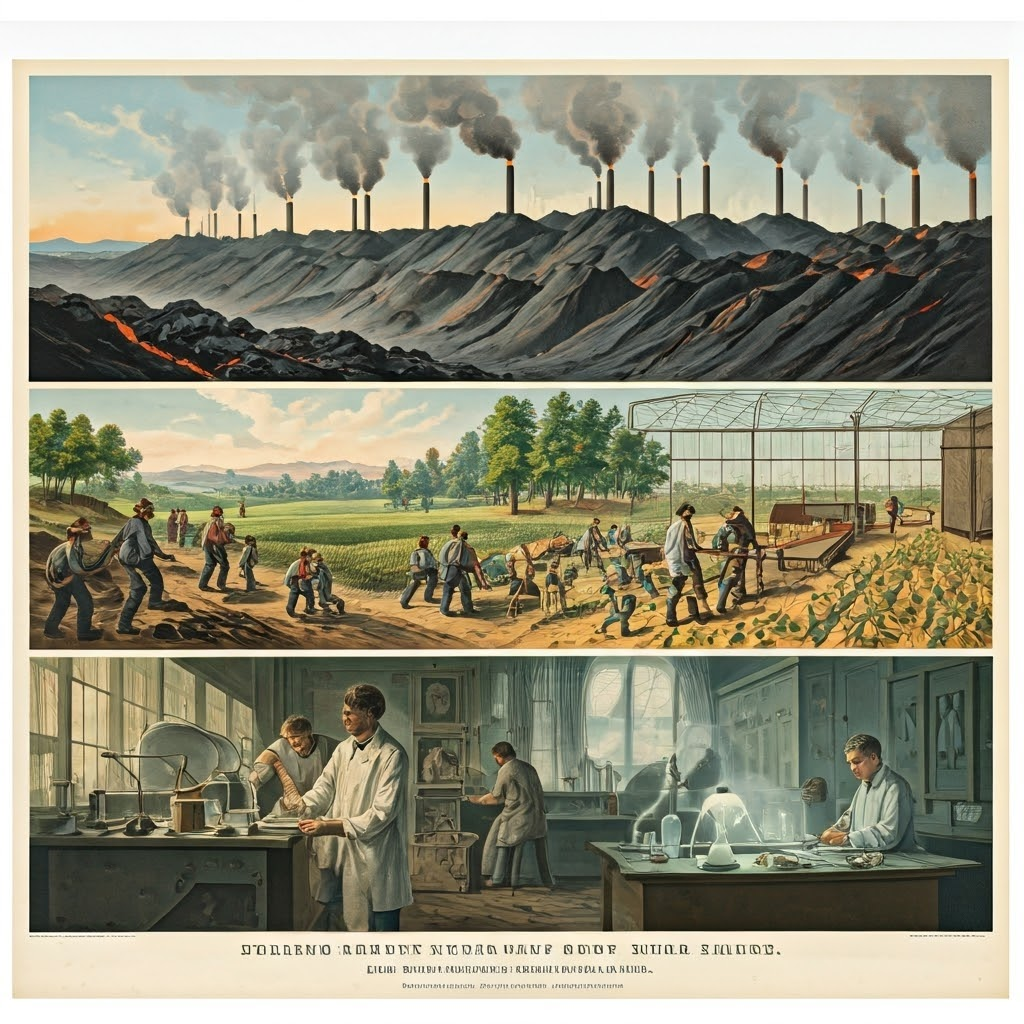

Britain’s coal, iron, and inventive engineers such as James Watt and Richard Arkwright drove this surge. Steam engines spun cotton and pumped mines, turning factories into money machines.

The government saw the value and acted. Laws barred the export of key machinery, blueprints, and even skilled workers, keeping industrial magic at home.

Other nations felt the squeeze. The United States, Germany, and Belgium paid high prices for British goods and wanted their own production—sparking a quiet race to steal or attract know-how.

Britain’s Head Start and the Race to Catch Up

Walls rarely stop ambition. Technology slipped out through legal exports when rules eased, but more often through daring schemes.

Samuel Slater, an English apprentice, memorized spinning-frame details and sailed to America in the 1780s. In Rhode Island he built the first successful U.S. mill. Britain branded him “Slater the Traitor.” Americans hailed him as the father of their Industrial Revolution.

Belgium recruited William Cockerill, who carried designs in his head to Liège. His family lured more British specialists and hid parts inside shipments labeled “agricultural equipment.” Skilled workers themselves became contraband, sneaking out under fake names for bonuses, land, or citizenship abroad.

Machines on the Move: Exports, Experts, and Espionage

Tariffs soon shaped the global game. The United States levied high duties on British cloth, shielding its infant mills but raising local prices.

Germany, led by Bismarck, mixed tariffs with heavy investment in railways and science education, sparking a technology race for cheaper, better machines.

Patents offered inventors rewards at home, yet many nations ignored foreign claims. Belgium openly copied British designs, treating them as public property.

Some firms thrived behind protection; others faltered when tariffs raised costs or lawsuits erupted. The tug-of-war between free trade and protectionism still echoes in modern trade disputes.

Tariffs, Patents, and the Game of Protection

Belgium industrialized first on the continent, using coal and British know-how to forge rails and textiles. The United States scaled production quickly, turning vast resources into mass-market goods. Germany blended scientific training with state backing, letting firms like Krupp and Siemens lead in steel, chemicals, and electricity.

Arriving later sometimes helps: newcomers skipped early missteps, refined ideas, and pushed past the original leader.

Belgium, USA, and Germany: The New Industrial Hotspots

Industrial spread reshaped lives. A Belgian miner earned more in factory towns. A British mechanic risked arrest for a fresh start in America. A German student landed a job at a thriving chemical firm. Each story shows how technology meant hope as well as profit.

The Personal Side: What It Meant for Ordinary People

The battle over ideas continues with semiconductors, medicines, and green tech. Borders may slow progress, yet curiosity keeps ideas moving. History proves knowledge travels, no matter how high the walls, inspiring each new industrial leap.