Ideas on the Boil: Coffeehouses, Satire, and the Public Sphere

Coffee, Conversation, and the Birth of Public Opinion

Picture a busy London street in 1720. Rain taps on slick cobblestones as you duck into a smoky coffeehouse. Voices mingle—merchants, printers, and philosophers trade news while strong, bitter coffee warms their hands. This mix of caffeine and talk sparks debate and reshapes how people see the world.

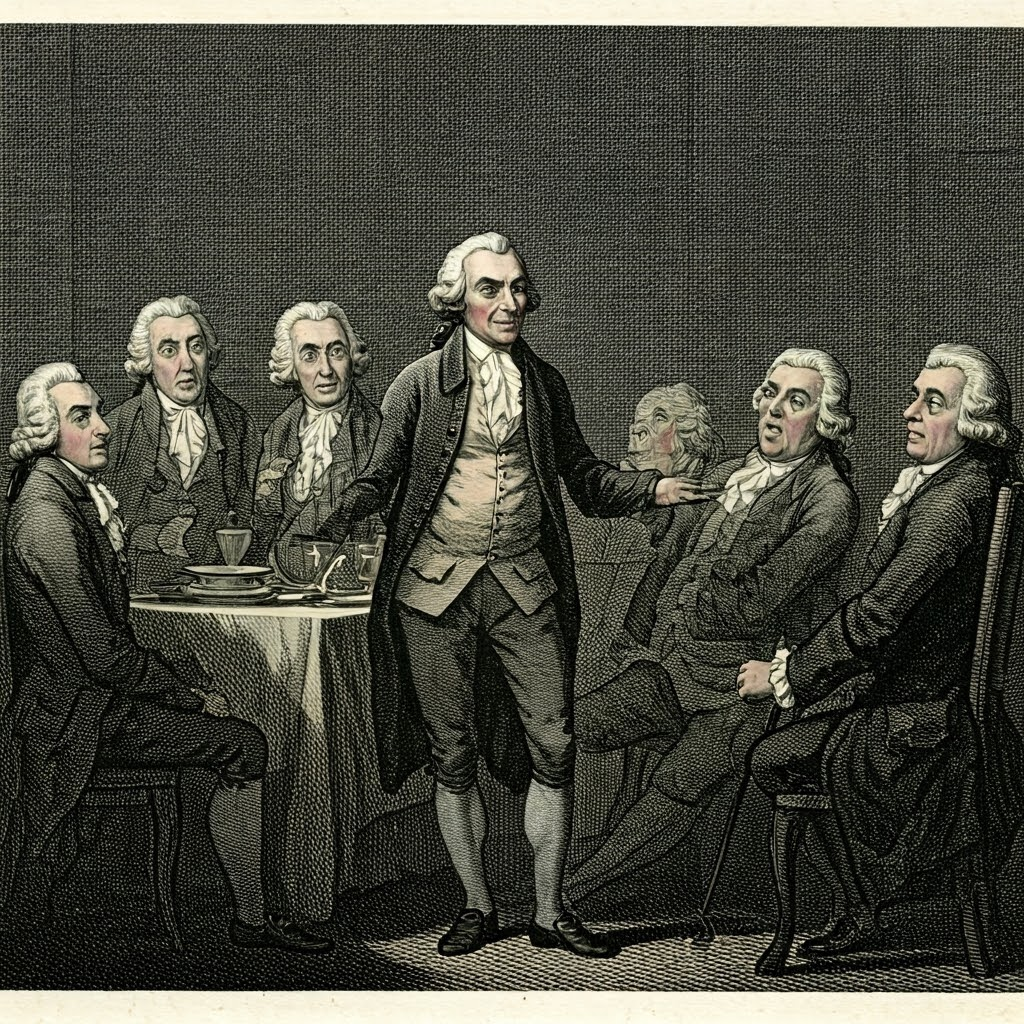

Coffeehouses felt oddly democratic. A shoemaker could challenge a lawyer, and ideas mattered more than rank. Newspapers slid from hand to hand, turning each table into a buzzing real-life feed. Across Europe these spaces formed the public sphere, letting ordinary people test fresh views on government, science, and art.

The philosopher Jürgen Habermas later called this sphere a bridge between private chat and official power. It let citizens shift from passive listeners to active political voices. That change, born in cafés, still shapes modern public life.

Before coffeehouses, most public talk unfolded in courts or churches. Now anyone could question taxes or a king’s divine right. Historian James Boswell noted that inside a London café “every man is an independent sovereign.” That sense of intellectual freedom proved contagious.

Satire: The Sharpest Pen in the Drawer

If coffeehouses were the public’s living rooms, satire became the spice that made ideas stick. Humor slipped past censors, poked the powerful, and lingered in memory. Voltaire, for instance, didn’t simply argue; he lampooned absolutism in Candide, making royal pretensions look ridiculous.

Satire was risky. Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal calmly suggested the poor eat their own children, exposing Britain’s cold policies in Ireland. Shocking readers let writers reveal cruelty that plain words might hide. Even simple cartoons with biting captions could topple reputations.

In France, Diderot packed the Encyclopédie with sly jokes amid lessons on science and philosophy. Laughter pulled audiences in and quietly seeded dissent—often before rulers noticed the joke pointed at them.

Why did satire work so well? Shared laughter made readers feel clever, part of an inside circle. Jokes loosened old beliefs, letting fresh questions grow. Sometimes even monarchs laughed—until crowds began chanting the same lines in the street.

Censorship, Secret Presses, and the Spread of Dangerous Ideas

Authorities fought back hard. Kings shut cafés, bishops burned books, and censors jailed writers. Voltaire landed in the Bastille; Diderot faced exile. The harder power squeezed, the more clandestine presses appeared in shadowy backrooms from Paris to Amsterdam.

Printers grew clever. A banned book might claim “London” on its title page while secretly printed in Amsterdam. Innocent-sounding works on gardening could argue for liberty or women’s rights. Shipments of wine or cloth hid pages that challenged thrones.

Ideas still raced across borders faster than any army. People copied pages by hand, memorized lines, or read aloud in secret meetings. Historians call it a battle of the books—authority versus freedom. Each pamphlet weakened old certainties and armed future revolutionaries with words as well as muskets.

The Ties That Bind: Talk, Laughter, and Change

Wonder how abstract ideals like liberty take root? Look where people meet to talk and laugh. The Enlightenment spread like wildfire through habits of reading, joking, and sharing news. Coffeehouses, satire, and hidden presses didn’t just entertain—they showed people new possibilities. Once seen, those dreams could never be unseen.