The Spark: Alexandria and the Birth of Big Questions

Picture a city where salty sea air mixes with papyrus dust and warm olive-oil lamps. Voices in many languages chase new ideas through narrow streets. Alexandria was more than a trading port; it was a crossing of minds from Babylon, Athens, Egypt, and Judea.

A City of Questions

Scholars flocked to a grand campus that joined a lush garden with quiet study halls. The Museum offered meals, stipends, and space to wander between fields. Mathematicians strolled past botanists, while playwrights borrowed star charts from astronomers.

The Library held hundreds of thousands of scrolls. Scribes copied every text they could find, even seizing books from incoming ships. That steady work let visitors explore geometry, geography, medicine, and myths without hitting a wall of missing pages.

Patrons, Scholars, and the Art of Asking

Patron kings funded housing, pay, and supplies for curious minds. This generous patronage turned questions into a full-time career. Friendly rivalry soon followed as each thinker tried to pose better problems and craft cleaner proofs.

Euclid wrote “Elements” here, starting with five simple axioms and building a sturdy framework of geometry. His clear structure urged later mathematicians to sharpen their logic and extend the field.

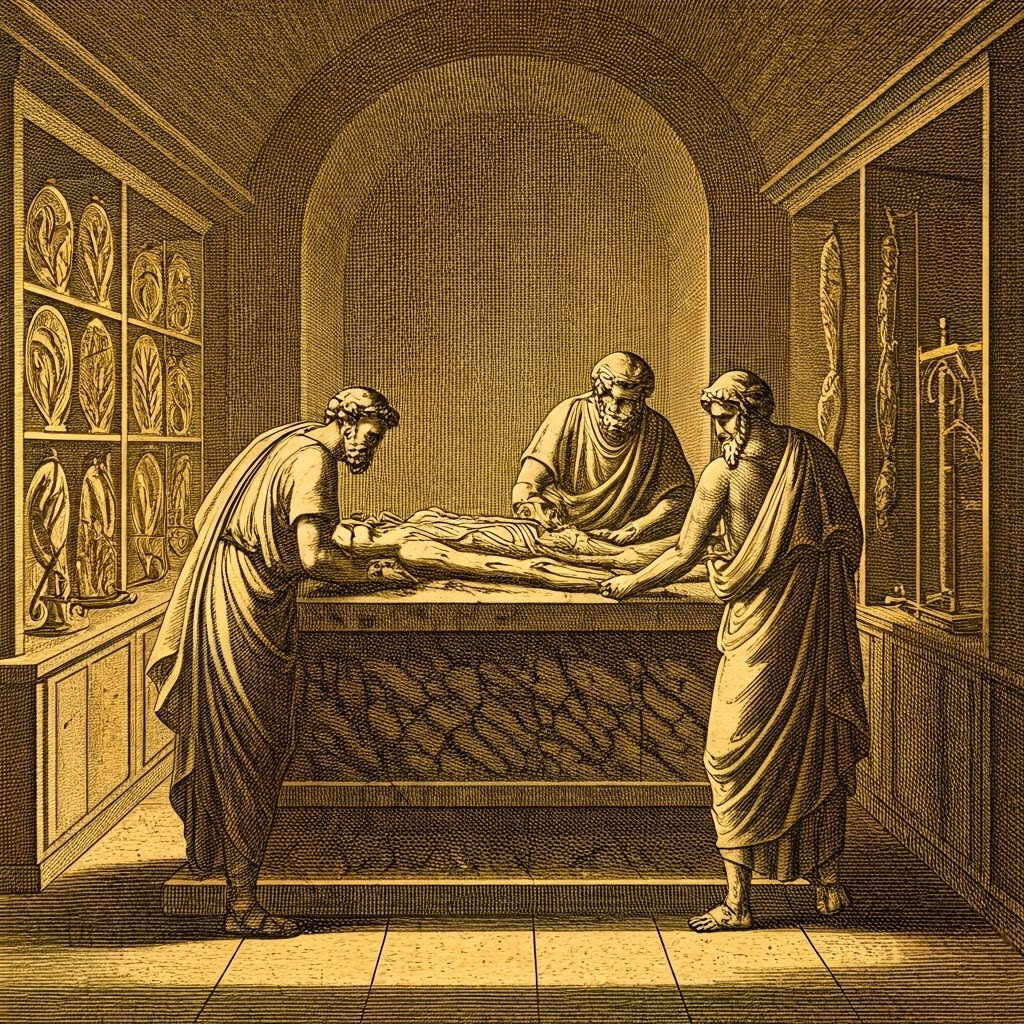

In medicine, rivals like Herophilus and Erasistratus dissected human bodies to map nerves and vessels. Their bold methods challenged old beliefs. Each critique forced the other to gather stronger evidence, pushing anatomy forward.

From Papyrus to the World

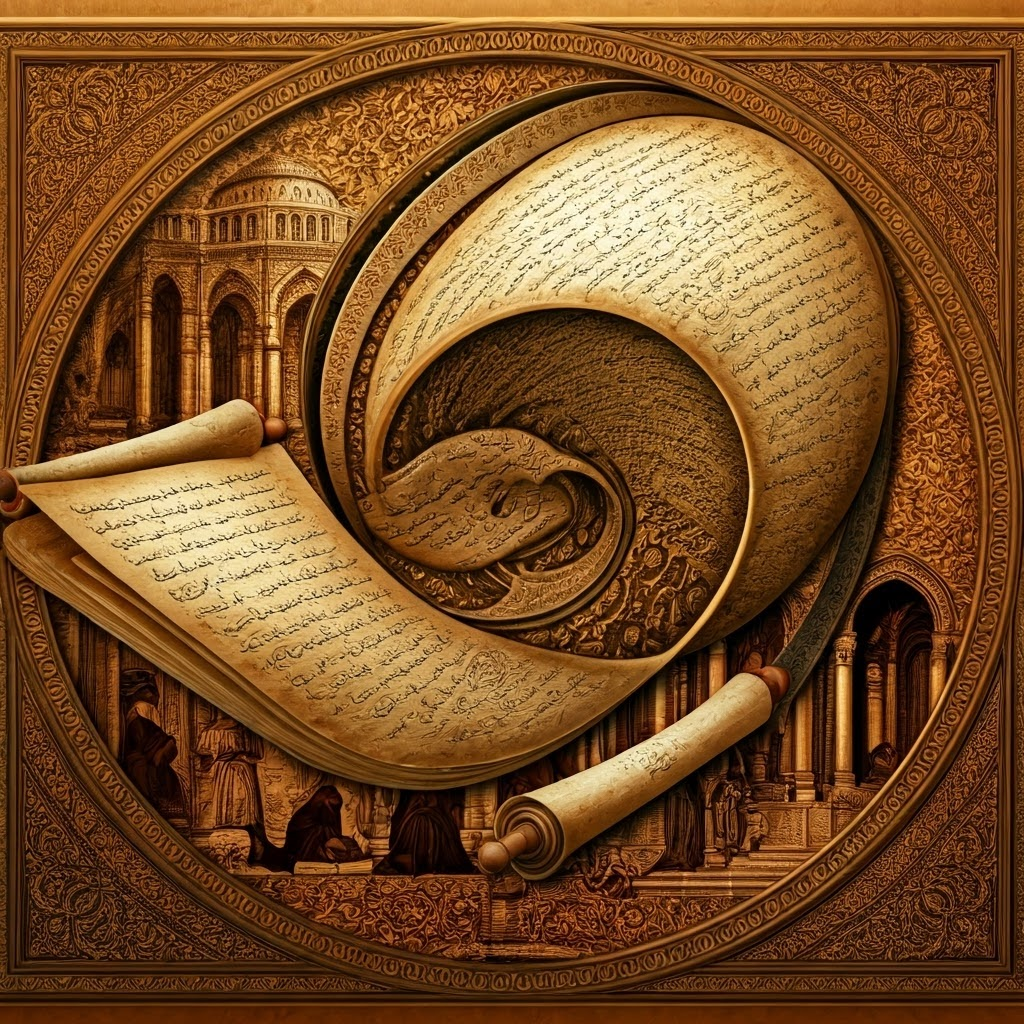

Ideas seldom stayed put. Couriers carried letters and fresh copies of scrolls to distant cities. These documents framed early scientific papers, sharing not just results but the method needed to repeat them.

Primary works like Ptolemy’s “Almagest” or Archimedes’ treatises still guide historians. Even lost writings echo through quotations, hinting at experiments with shadows, levers, and planetary paths.

Centuries later, Arabic translators in Baghdad, Córdoba, and Cairo copied and commented on these texts. Their fresh insights merged with the originals, then flowed into Latin during the Renaissance. This relay—copy, translate, question, pass on—kept curiosity alive and set the stage for modern science.