Ships, Fortresses, and the Race for the Sea

Why the Sea Became the Prize

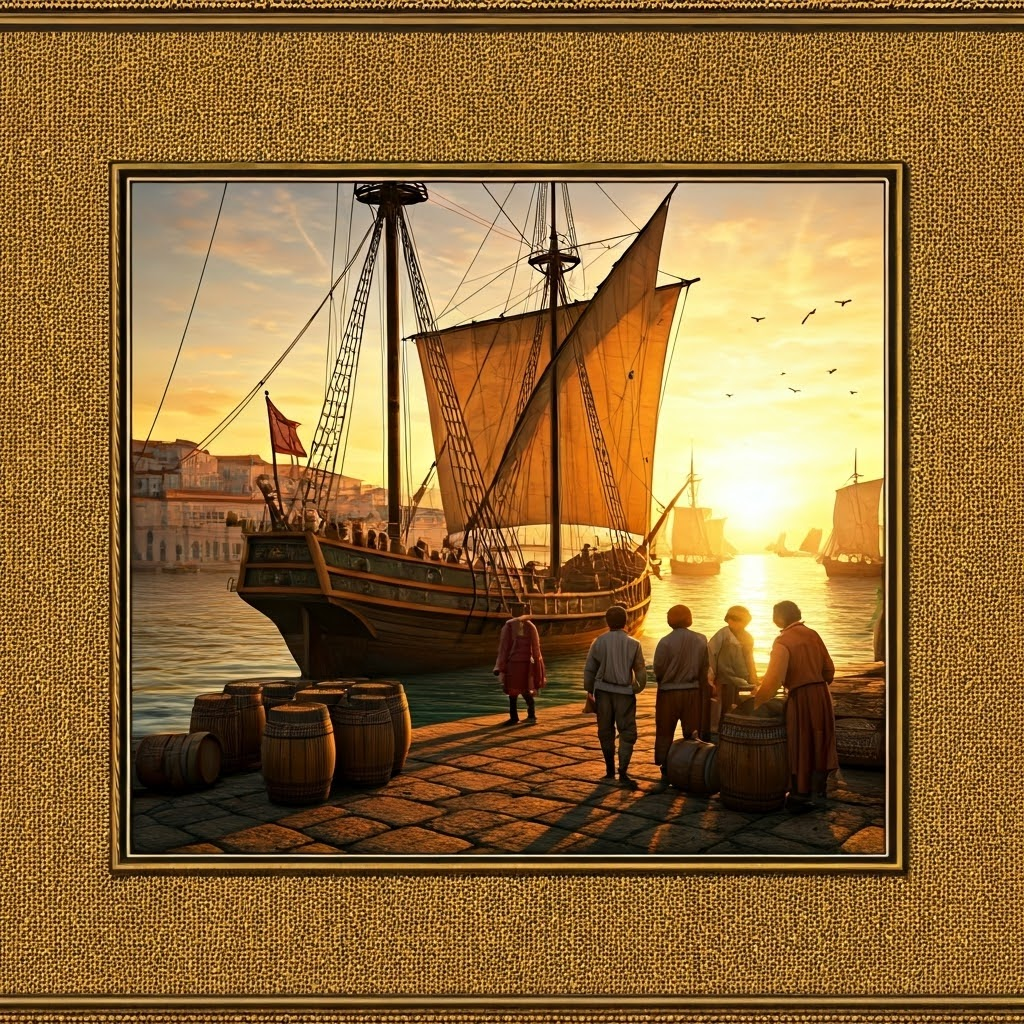

Picture yourself on Lisbon’s busy docks in 1500. You stare at barrels of pepper—each one as valuable as gold—because land routes are slow and blocked by rivals. The ocean looks risky, yet its promise of quick riches pushes merchants to sail anyway.

Portugal and Spain see the ocean as a highway, not a barrier. Spices, silver, and fresh markets can make rulers rich and nations powerful. Storms, pirates, and disease add fear, but the chance to set the world’s rules keeps bold sailors on the move.

Portugal’s Edge: Fortress-Factories and the Estado da Índia

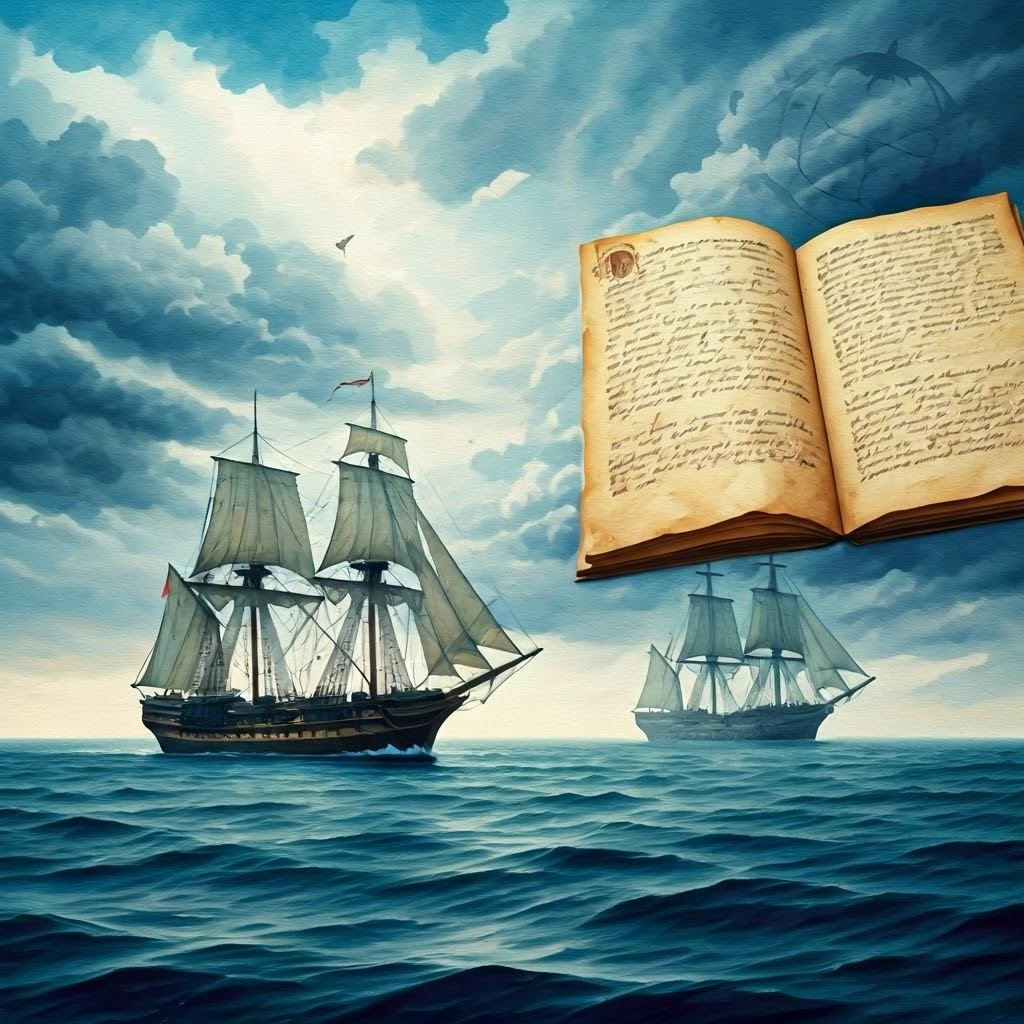

Imagine a Portuguese ship coasting past Africa. It stops at Elmina, then Mombasa, Malacca, and Goa. Each post is a stone fort with cannons, warehouses, and soldiers. These small strongholds guard chokepoints, charge passing vessels, and form the Estado da Índia.

The network works like armed toll booths. Portugal skips costly inland wars and instead holds narrow straits, river mouths, and safe harbors. Control of these knots lets Lisbon tax trade and shelter its own ships, turning limited manpower into global reach.

Spain’s Silver Highway and the Manila Galleons

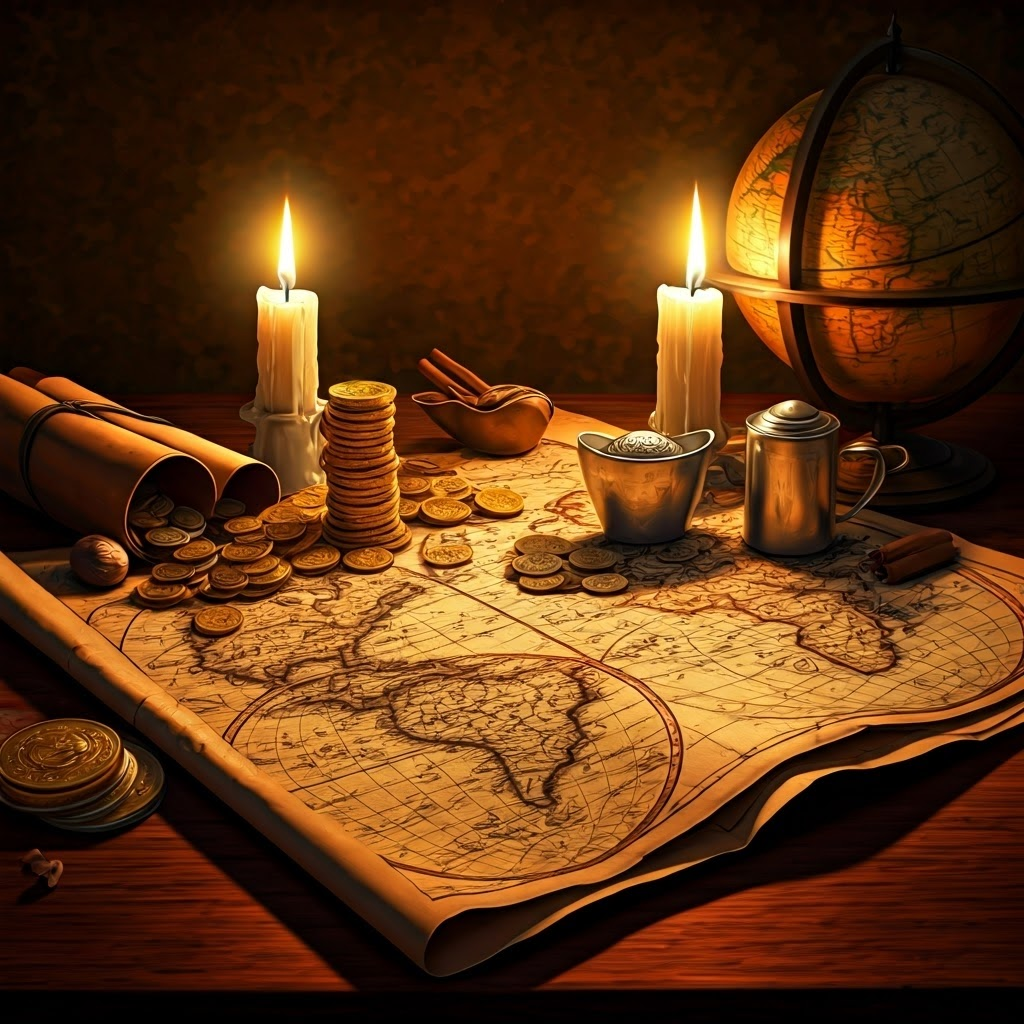

A Spanish galleon leaves Veracruz loaded with silver ingots. It sails in the Carrera de Indias, a tightly guarded convoy bound for Seville. Silver funds Europe’s wars, pays Asian silk bills, and settles debts. Pirates and hurricanes stalk every fleet.

Most treasure comes from Potosí in modern Bolivia. Spain packs ships with guns and seasoned crews because one lost convoy could cripple royal finances. The lure of riches keeps sailors gambling their lives on each Atlantic crossing.

Spain’s Pacific link is the Manila Galleon. Once or twice a year, huge ships haul Chinese goods to Mexico, then return with American silver. Six brutal months at sea, storms, and scurvy claim many lives, yet profits stay enormous.

Dutch Innovation: The VOC and the Fluyt

The Dutch form the VOC in 1602—a joint-stock company where investors share risk and reward. This corporate model lets Amsterdam raise vast capital fast, funding fleets without royal coffers. Paper shares turn ordinary citizens into stakeholders.

Dutch shipyards add the fluyt: wide, cheap, and crew-light. Its odd boxy form dodges high tolls and hauls bulk cargo efficiently. Lower costs mean lower prices, letting Dutch traders undercut rivals from Lisbon to London.

English and French: Privateers, Companies, and Competition

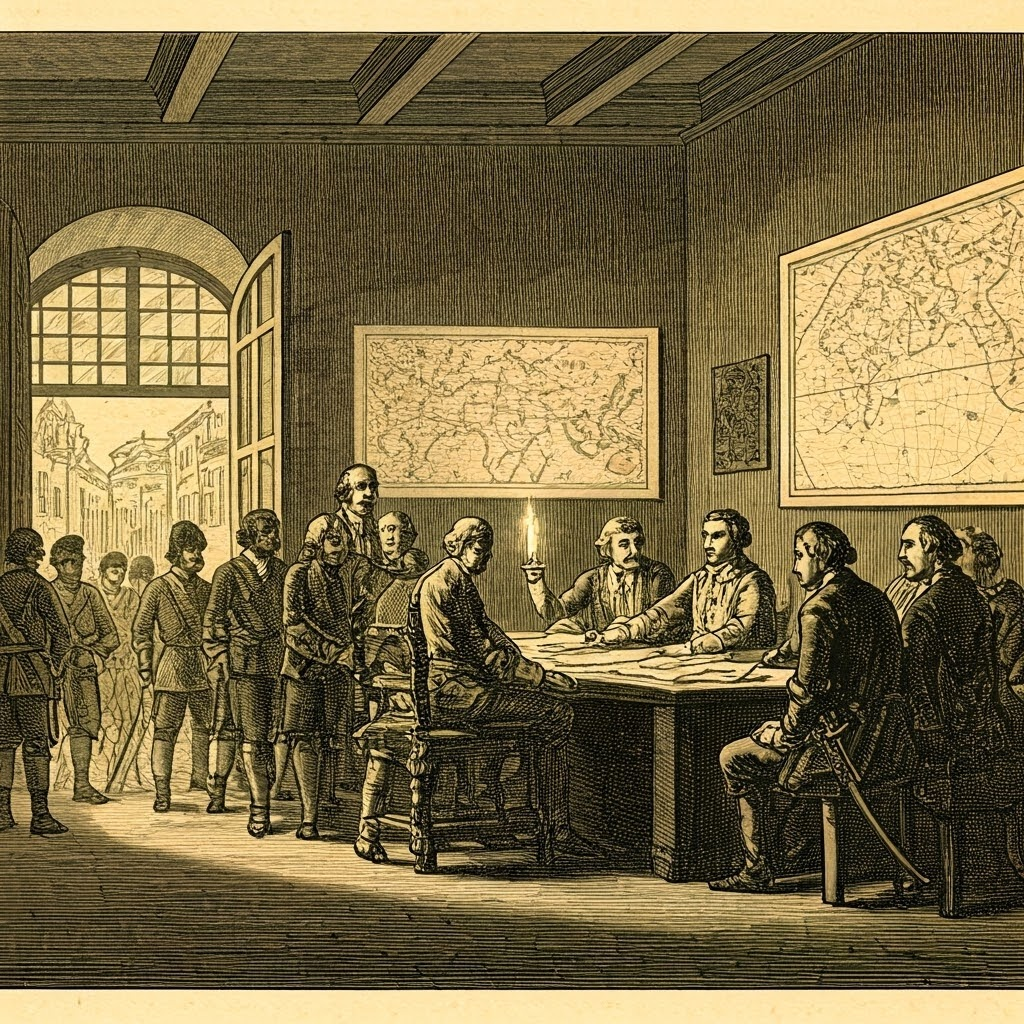

England and France arrive late but fight hard. They license privateers—pirates with paperwork—to raid enemy shipping. Francis Drake storms Spanish treasure ships and keeps part of the loot. The crown gains both gold and a tougher navy.

Both nations also create chartered companies like the English East India Company. Granted monopolies, these firms run forts, hire armies, and sign treaties. By 1757 the English company shifts from trading in Surat to ruling provinces after the Battle of Plassey.

Privateering, chartered companies, and constant ship design races all carry heavy risk. Storms, mutiny, or rivals can end fortunes overnight. Yet these sea empires sketch the blueprints of today’s global economy, turning the world’s oceans into its first true battlefield.