The Spark: How Neurons Start the Conversation

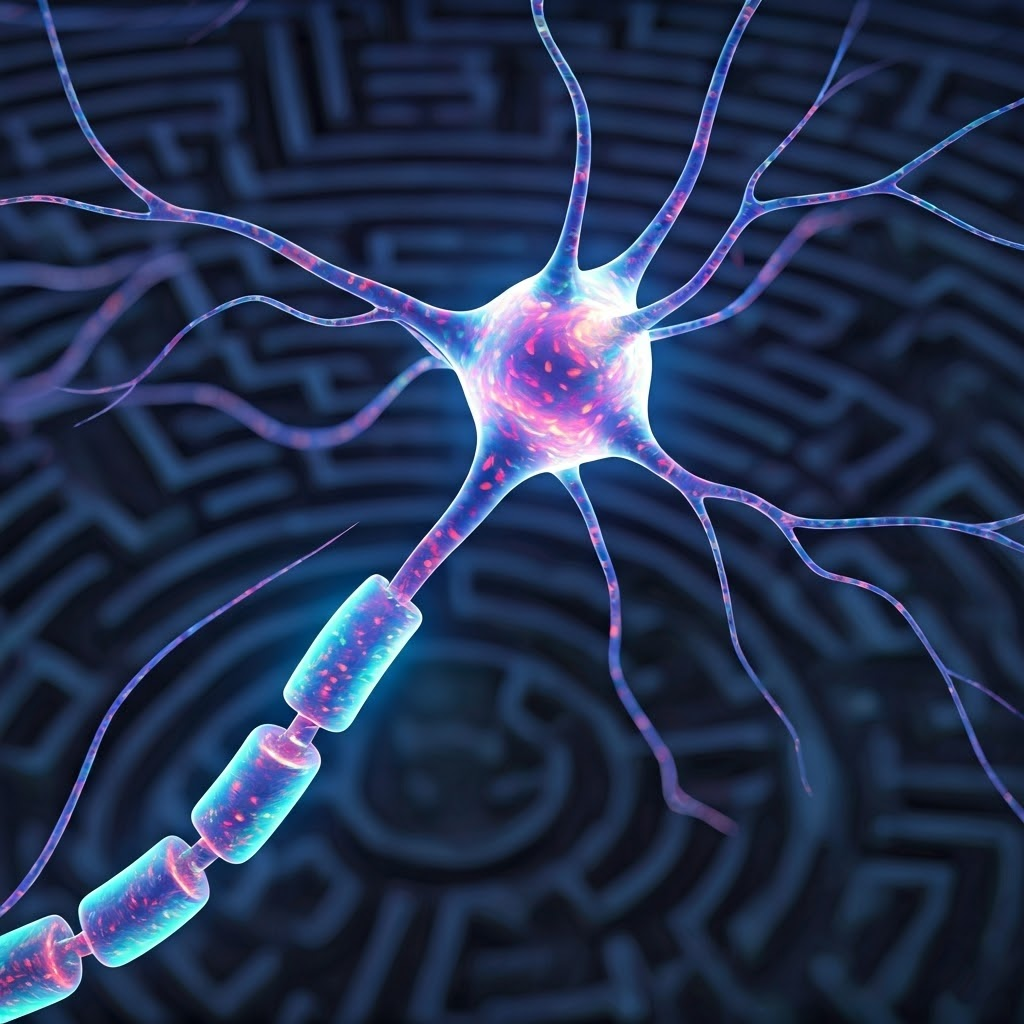

Meet the Neuron: The Brain’s Messenger

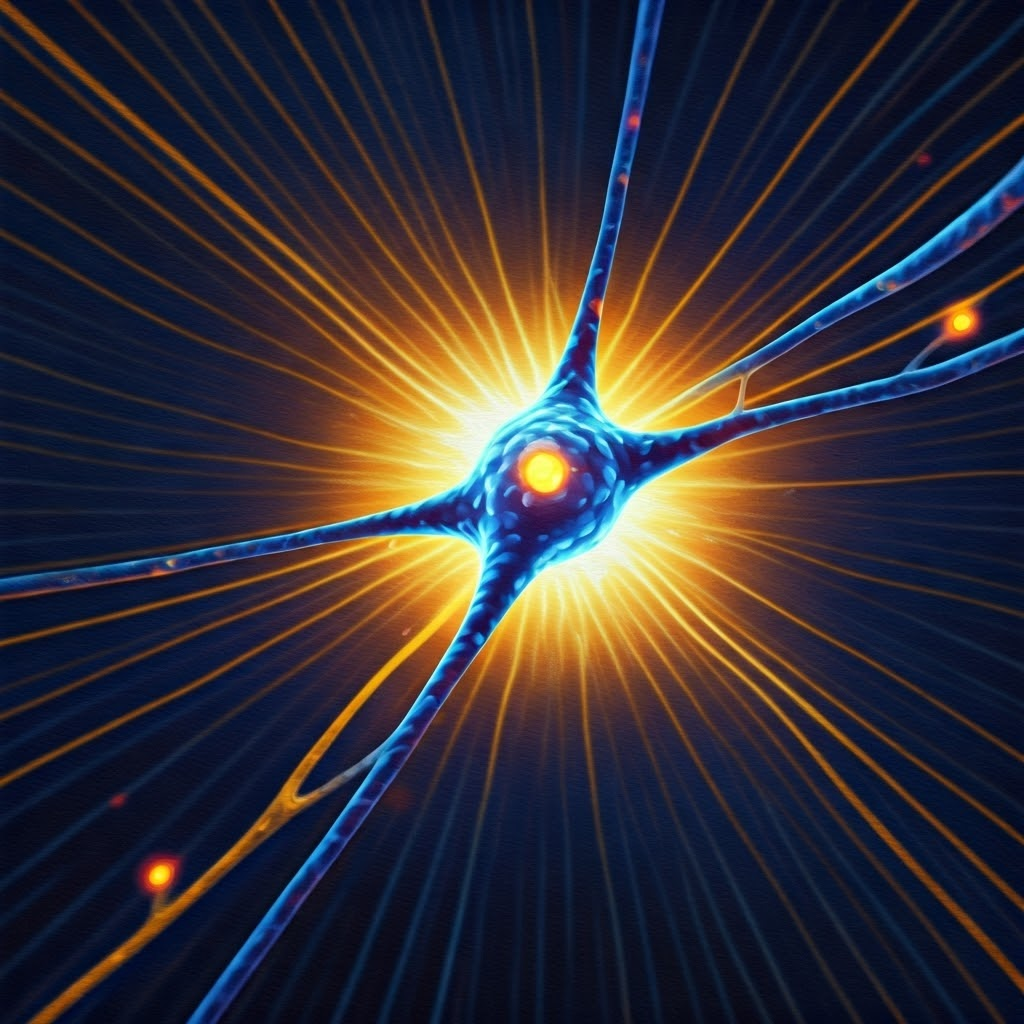

A neuron works as the brain’s swift messenger. It sends and receives signals that create every thought, feeling, and memory.

While a skin cell stays put, a neuron races along neural paths, carrying information between distant regions.

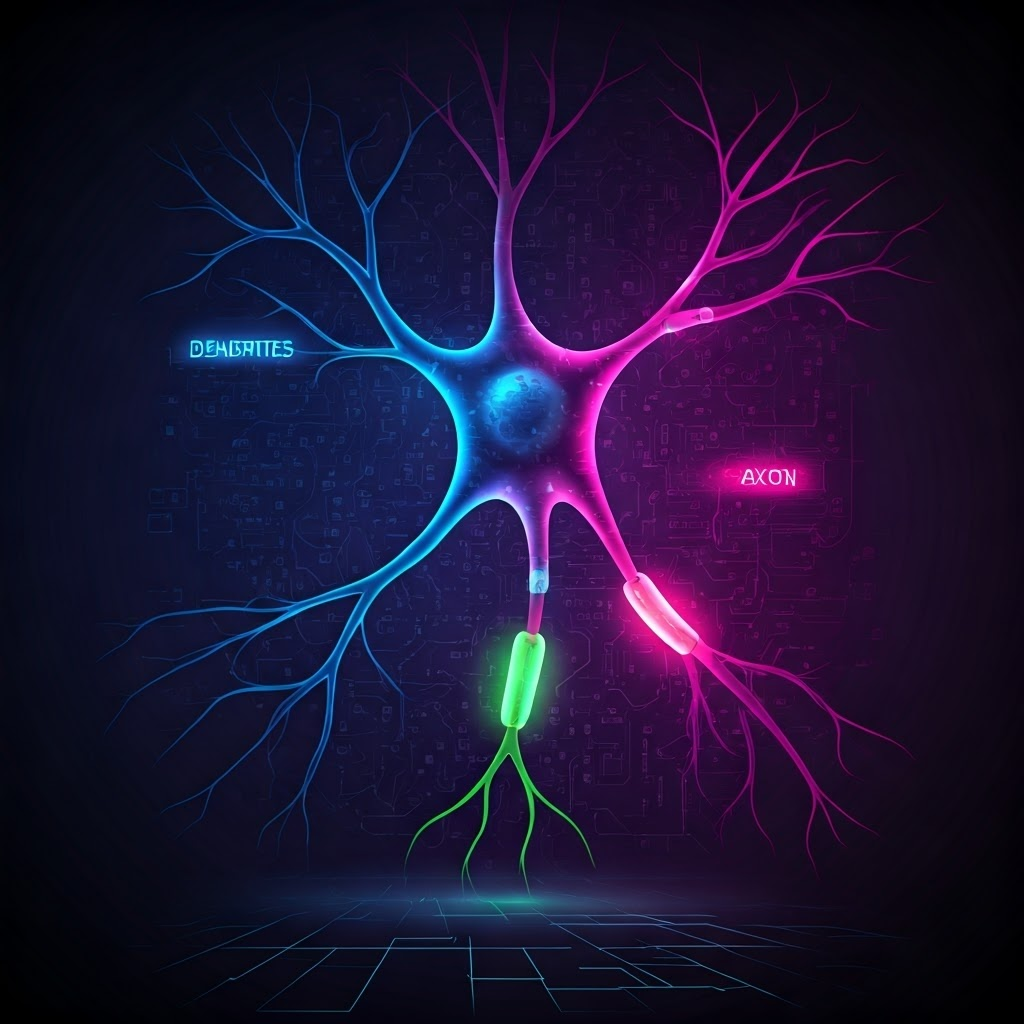

Each neuron has three main parts that share the load. Dendrites act like tiny antennae, the soma processes input, and the axon delivers the response.

At the axon’s end lies a slim gap called the synapse. Here the signal must leap to reach the next cell, completing the circuit.

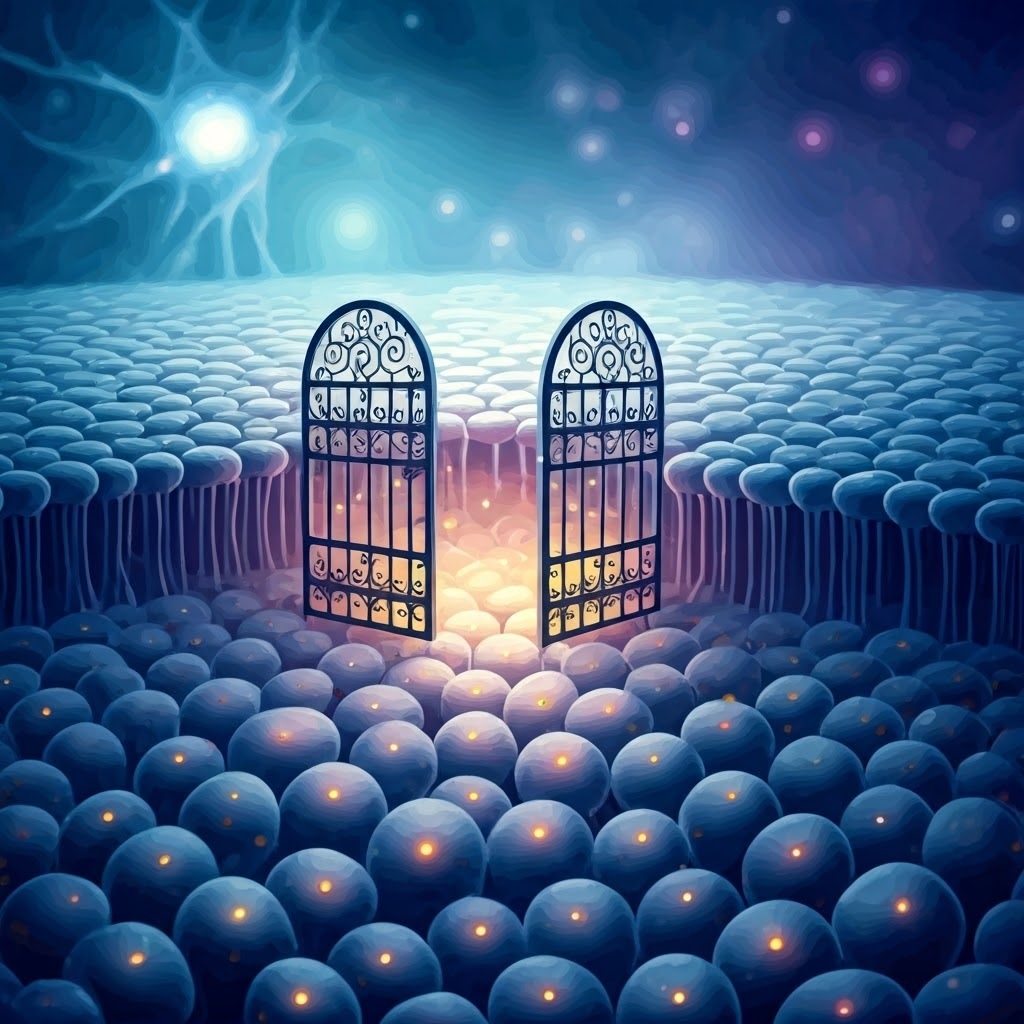

Ion Channels: The Gates That Control the Flow

The real magic hides in the membrane. Tiny ion channels work like gates that let charged sodium and potassium slip through.

Most gates stay closed, keeping the inside negative and the outside positive—like a small, ready battery.

Some channels react only to voltage. These voltage-gated channels swing open when the membrane reaches a set level, letting ions flood in or out and flipping the charge.

Threshold: When Enough is Enough

A neuron ignores weak nudges. It fires only when input lifts the membrane to the threshold—about −55 mV.

Picture filling a glass. Each drop is a signal. Nothing spills until the rim is passed, then water rushes out. The same rule starts the nerve impulse.

The threshold filters noise. Only combined, meaningful inputs launch an impulse, keeping brain traffic clear and organized.

Action Potential: The Big Event

Cross the threshold, and an action potential races ahead like a firework.

First, voltage-gated sodium channels burst open, and sodium floods in—depolarization flips the inside positive.

In milliseconds, sodium channels shut, potassium channels open, and potassium exits—repolarization returns negativity.

The charge dips slightly lower—hyperpolarization—then resets, ready for the next burst.

Each action potential is all-or-nothing. After firing, the neuron enters a quick refractory period, preventing back-to-back signals from overlapping.

Propagation: Sending the Signal Down the Line

The impulse must travel the axon. Like lit matches in a row, one excited patch sets off the next—this is propagation.

Many axons wear myelin, a fatty wrap that insulates them. The signal leaps over each wrap to nodes of Ranvier in a rapid hop called saltatory conduction, reaching up to 120 m/s.

Damage to myelin, seen in multiple sclerosis, slows or blocks these vital messages.

At the axon’s end, the impulse triggers neurotransmitter release across the synapse, sparking the next neuron. Every move, memory, or emotion begins with this small but powerful electrical wave—the brain’s enduring spark.