From Shocks to Sparks: The First Encounters

Curiosity and Static: Thales to the First Experiments

You feel a little snap when you touch a doorknob after shuffling across carpet. That quick jolt is static. Over 2,500 years ago, Thales of Miletus noticed a similar effect when he rubbed amber with fur and saw straw jump toward it.

Electricity traces its name to elektron, the Greek word for amber. Early observers saw combs lift hair and stones push or pull without contact. They kept simple notes, rubbing objects and watching what stuck. These playful trials sparked curiosity that spread across the ancient world.

By the 1600s, investigators grew methodical. William Gilbert compared magnetism and electricity, coining fresh terms and crafting glass rods rubbed with silk to produce larger sparks. Though still closer to party tricks than power, each flash deepened knowledge and inspired even bolder tests.

Lightning in a Jar: Franklin and the Kite

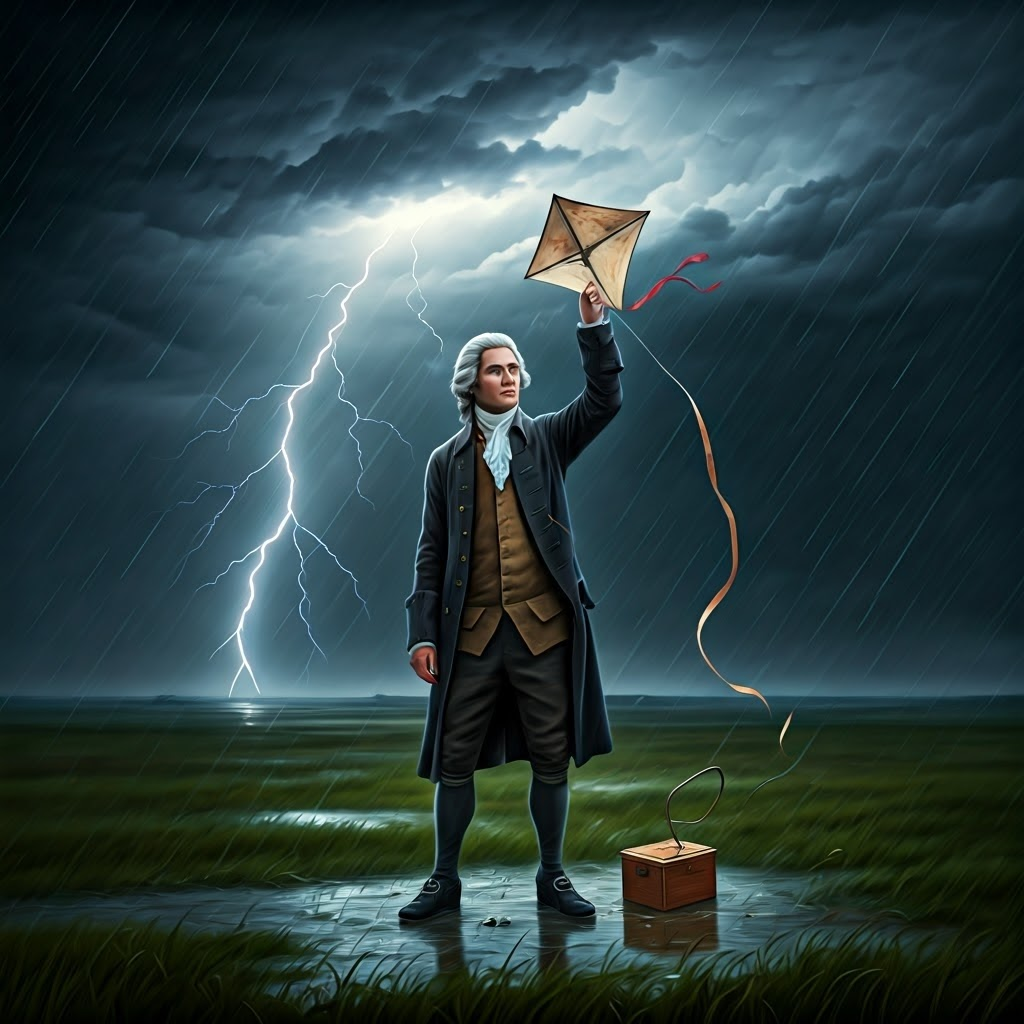

In 1752, Benjamin Franklin wondered if storm lightning matched indoor sparks. He launched a silk kite into dark clouds, a metal key dangling from the wet string. The soaked line carried charge downward while he held a dry ribbon. When the key hissed and glowed, his experiment answered yes.

Franklin’s proof linked household shocks to towering bolts. His daring also promoted safety, leading to lightning rods on rooftops. The episode showed that electricity obeys rules humans can study and harness. That insight turned raw storms into a field ripe for innovation.

The First Theories: What Did They Think Was Happening?

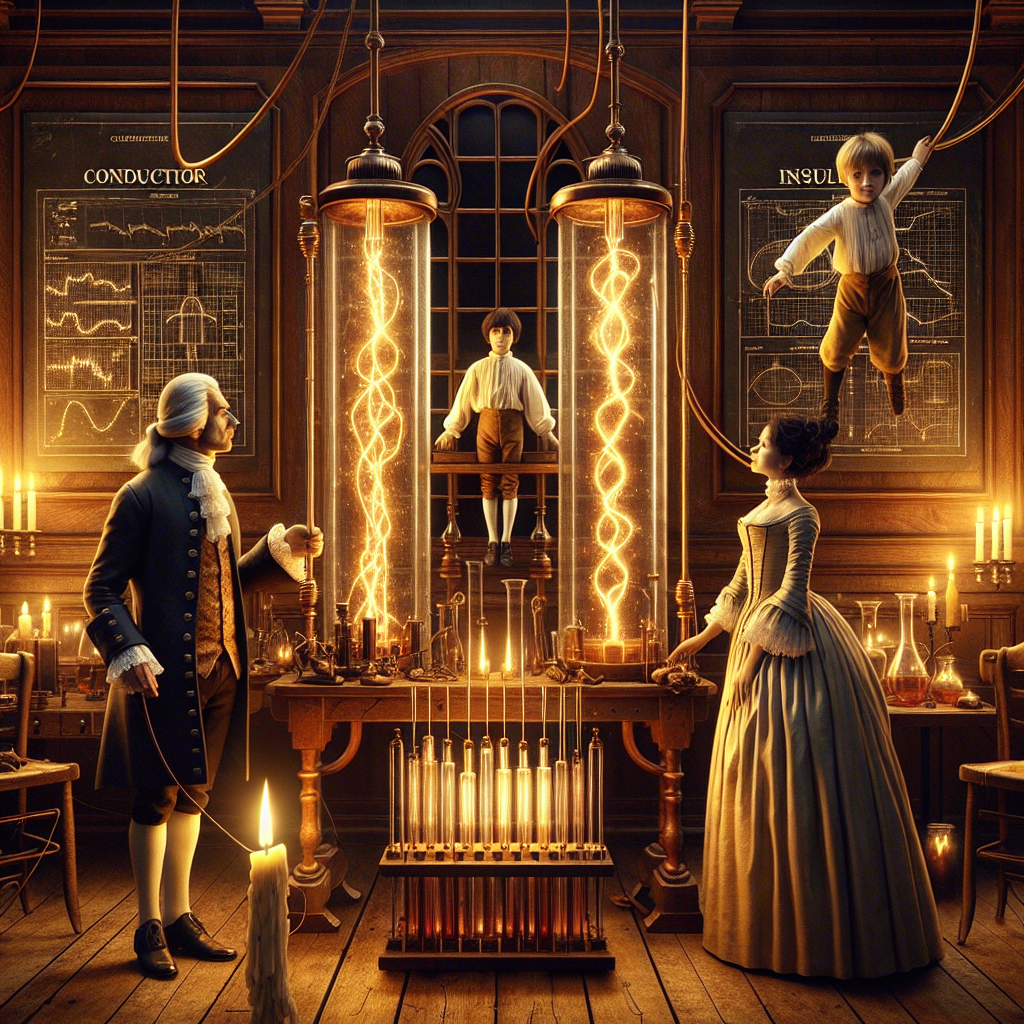

With sparks now reproducible, thinkers hurried to explain them. Some pictured a special fluid flowing through matter, others imagined an invisible spirit. Stephen Gray’s “flying boy” revealed that certain materials conduct while others insulate, yet the true nature of the force stayed out of reach.

Charles du Fay argued that two fluids existed—vitreous and resinous—while Franklin favored one fluid and a balance between positive and negative. Debates filled lecture halls and salons. The Leyden jar, an early capacitor, stored hefty charges and allowed repeatable tests that gradually sharpened collective insight.

Step by step, researchers sorted conductors from insulators, matched sparks to lightning, and learned electricity can travel across distance. Their homemade gadgets lacked precision yet built a framework future engineers could trust. Each modest trial moved society closer to controlled power.

Why Early Sparks Still Matter

Those first shocks did more than entertain. They pushed people to search for patterns, design tools, and question old beliefs. From amber tricks to Franklin’s stormy night, every daring act showed that nature’s rules could be discovered—and that set humanity on a path of electrical progress.

Today’s motors, lights, and phones descend from those early experiments. Remember that each spark—no matter how small—added evidence, refined ideas, and encouraged the next leap. The story of electricity began with curiosity, persisted through debate, and keeps lighting new ways forward.