Building the People’s Power: How Athens Got Democratic

Cleisthenes and the Birth of a New System

Before Cleisthenes, a handful of aristocratic families ran Athens. Farmers and craftsmen had almost no say.

In 508 BCE, Cleisthenes sought wider backing. He scrapped the four old tribes and created new ones that mixed citizens from every region.

Each person now belonged to a deme—a local district that became a lifelong political label.

Identity shifted from bloodline to residence. That move weakened clan power and spread representation.

Cleisthenes and the Birth of a New System (Continued)

He grouped these demes into ten tribes that blended coastal, inland, and urban people. Regional blocs lost their grip.

The tribes supplied fifty citizens each to a boule of 500. Lots picked them yearly, blocking bribery and heredity.

Ordinary men now managed state tasks. Chance, not wealth, opened office doors.

Who Got to Be a Citizen?

True citizenship now needed two citizen parents and deme registration. Pericles’ 451 BCE law barred mixed-parent children.

Rights followed status: vote, speak, serve on juries, own land. Women, slaves, and metics paid taxes yet stayed outside this privilege.

The fight over inclusion mirrors modern debates on belonging and prestige.

The Ekklesia: The People’s Assembly

Any adult male citizen could join the open-air Assembly on Pnyx Hill.

Registrars kept slaves out. Under the sky, long debates set war plans, budgets, treaties, or ostracisms.

Votes passed by raised hands. Orators often steered opinion, yet every voice had a legal right to speak.

The Boule and the Prytany: Running the Show

The boule of 500 set agendas, watched finances, and oversaw laws.

Each tribe’s fifty members served one year. Inside, a rotating group called the prytany led business for about six weeks.

Daily lots even picked a chairperson. Constant turnover kept power reachable and trustworthy.

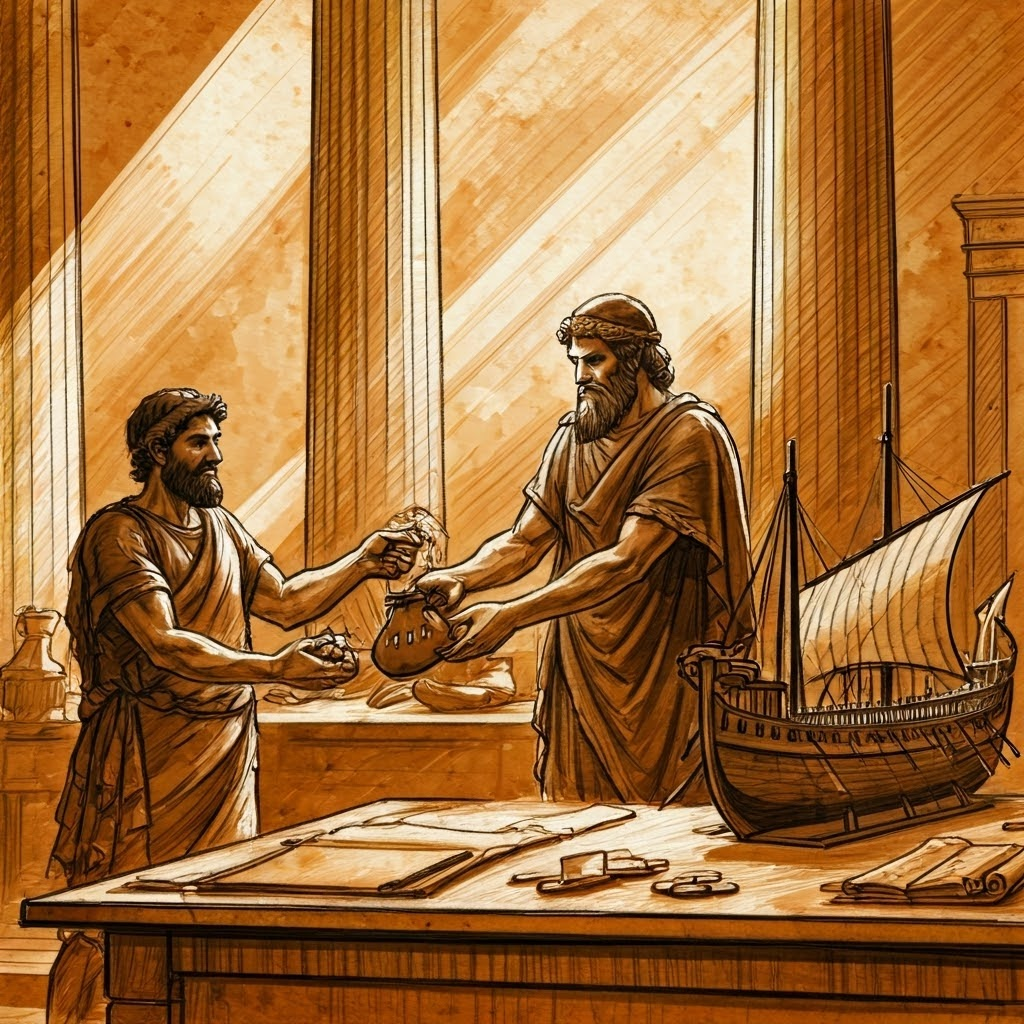

Pay, Liturgies, and Trierarchies: Who Paid for Democracy?

Athens paid small stipends, or misthos, to jurors and Assembly goers. Poor citizens could now attend without losing wages.

Costly festivals, theaters, and triremes fell on the rich through liturgies. The priciest, the trierarchy, forced one man to outfit a ship for a year.

Failure to serve triggered lawsuits and public shame.

Everyday Life in a New Political World

Citizens now voted, joined the boule, or bankrolled projects. Frequent lotteries stopped elites from locking in control.

Chance offered any man a day—or a year—in office. Shared duties built unity, though women, slaves, and foreigners stayed excluded.

Despite flaws, Athens sparked later republics by proving ordinary people could steer a state.