Electricity: The Invisible Push

Electricity is an unseen push that moves tiny charged particles. It powers everything from phone chargers to city trams, yet we rarely notice it until a small shock grabs our attention.

What Is Electric Charge?

Every object is built from atoms that hold protons and electrons. When these charges stay balanced, nothing special happens. Shuffle across a rug, and you steal extra electrons from the carpet. Now your body has more negative charge than the doorknob. Touch metal, and those electrons jump away—producing a tiny spark. Opposite charges attract while like charges repel, which makes charged hair strands push apart and stand up.

Static shocks hint at a larger story. All electrical devices rely on electrons moving through materials, just on a far grander scale than your sweater experiment.

Voltage, Current, and Resistance: The Flow and the Block

Picture a water park. Voltage is the pressure that pushes water. Current is the volume flowing. Resistance is the narrow twist that slows it down. Plug in a phone, and the charger’s voltage pushes electrons through the cable. Thick, short wires have little resistance, so current stays high and charging is quick.

Remember the trio:

- Voltage (V) – the push.

- Current (I) – the flow.

- Resistance ® – the squeeze.

Connect a battery to a bulb. Voltage drives charges around the loop. The filament’s slim wire resists the flow, heats up, and glows—turning electrical energy into light.

Ohm’s Law: Why Your Phone Charges (or Doesn’t)

Ohm’s Law links the three ideas:

Increase voltage or lower resistance, and current rises. A 5-volt charger and a 2-ohm cable deliver 2.5 amps. Swap in a flimsy 5-ohm cord, and current drops to 1 amp, so charging slows. Too little resistance can swing the other way, overheating wires and risking damage.

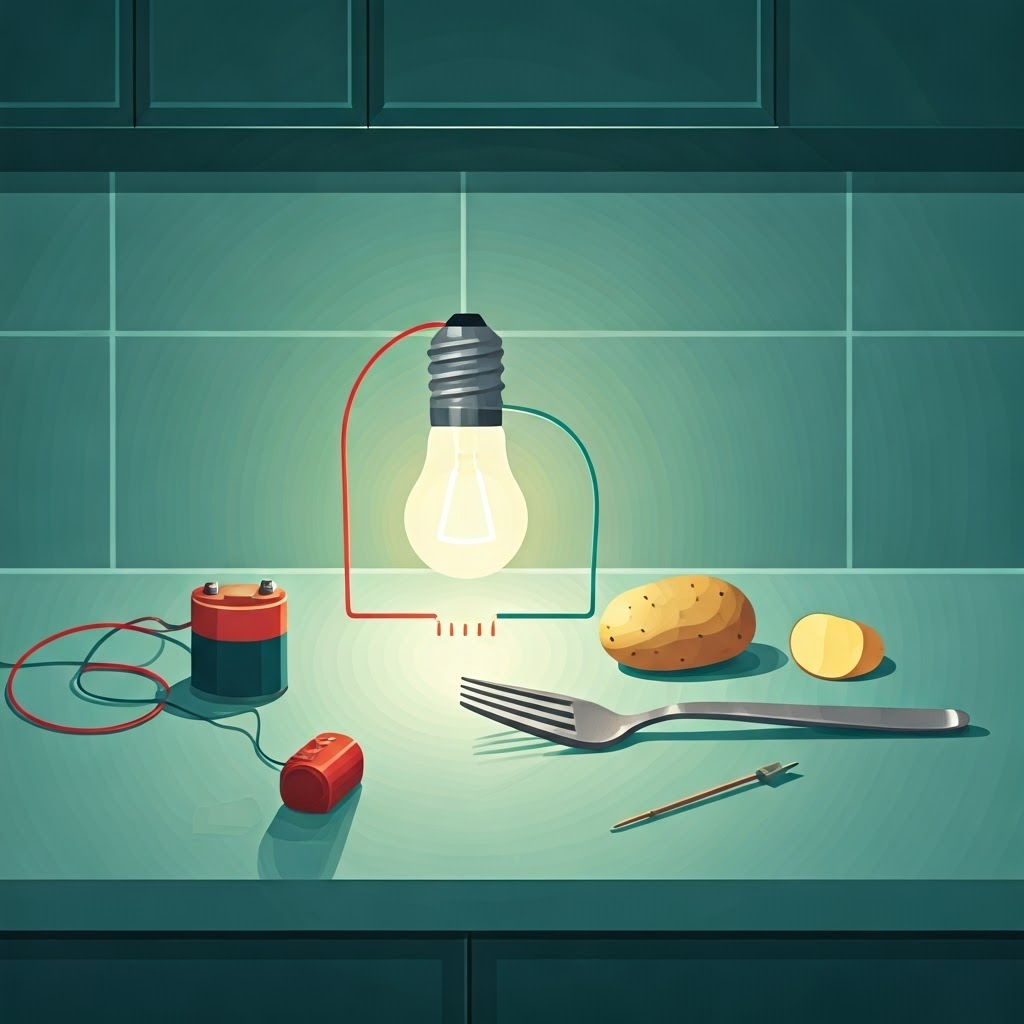

Testing Conductors: What in Your Kitchen Can Carry a Current?

Build a simple circuit with a battery, two wires, and a flashlight bulb. Leave a gap in one wire for a test item. If the bulb lights, the material is a conductor—metals shine here. If darkness remains, you’ve found an insulator like plastic. Even a wet potato glows faintly because salty water carries charge.

Why Batteries Have Two Ends

A battery works as a tiny charge pump. The negative end pushes electrons out, while the positive end pulls them back. Complete the loop with a wire, and electrons march in a circle. Reverse the battery, and the push flips—most gadgets simply stop, and sensitive ones may break, so always match plus and minus signs.

Everyday Experiments and the Big Picture

Charges, voltage, current, and resistance shape daily life—from static zaps to warm toast. Understanding how conductors, insulators, and Ohm’s Law fit together lets you see the hidden dance of electrons that powers your world.