Black Holes: Where Gravity Gets Weird

What Makes a Black Hole?

Gravity gets extreme near a black hole. A huge star runs out of fuel, its core collapses, and matter squeezes into a space so small that light itself cannot escape. The result is a black hole—a cosmic region where gravity rules everything.

A black hole is not special because of mass alone but because that mass sits in a tiny volume. Imagine Earth shrunk to a marble. Surface gravity would become overwhelming. Black holes push this idea further, showing how density turns space-time into a trap.

Gravity depends on mass and distance. Pack the same mass into a smaller radius, and the pull at the edge rises sharply. Black holes take this to the limit, turning space into an inescapable well. They challenge every known law, making physicists test the edge of physics.

The Point of No Return

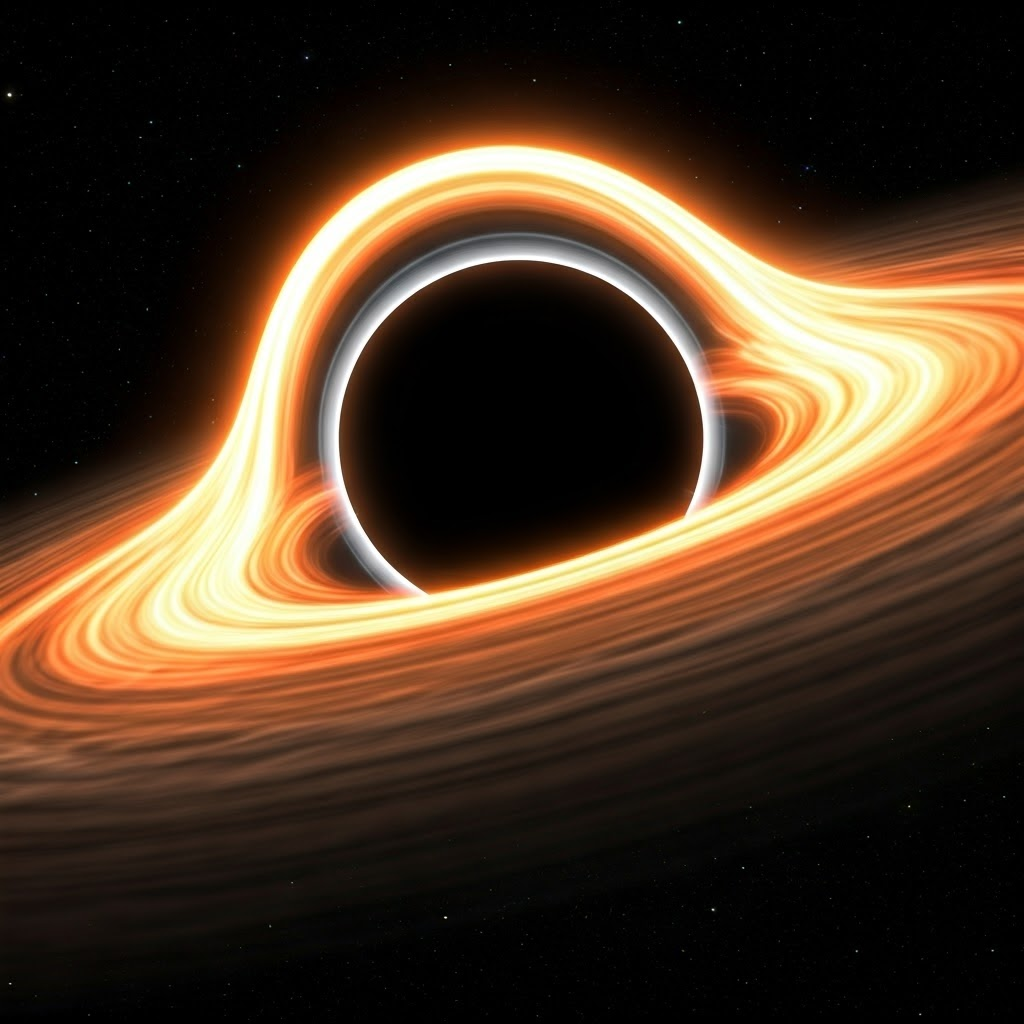

Close to a black hole lies the invisible event horizon. Cross it, and nothing can come back—not even light. For outside observers, infalling objects appear to slow and fade. For the traveler, passage feels uneventful, yet escape is impossible.

The event horizon’s size scales with mass. Its radius follows . A solar-mass black hole would have a horizon roughly three kilometers wide. Although intangible, this boundary sets the ultimate speed limit—light itself cannot beat gravity here.

Feeding Frenzies and Cosmic Jets

Black holes often dine on nearby gas. Material forms a bright, spinning accretion disk, heating to millions of degrees and shining in X-rays. These disks make some of the universe’s brightest beacons, despite the black hole itself staying dark.

Sometimes, trapped gas escapes as narrow beams called relativistic jets. They race outward at near-light speed, stretching across entire galaxies. The jet in galaxy M87, photographed by the Event Horizon Telescope in 2019, showcases this raw cosmic power.

How We Spot the Invisible

Astronomers hunt black holes by their effects. In X-ray binaries, a normal star orbits an unseen companion. Gas spirals in, heats up, and emits X-rays we detect on Earth. The dark partner’s gravity reveals its presence.

Another clue comes from gravitational waves. When two black holes merge, space-time ripples. LIGO and Virgo first heard this cosmic chorus in 2015, confirming collisions of massive unseen objects.

The worldwide Event Horizon Telescope links radio observatories to image a black hole’s shadow. Though Hawking radiation remains too faint, such creative techniques keep exposing these hidden giants. Black holes remind us that the universe still holds many secrets waiting to be understood.