The Apple, the Sky, and the Scholar

Woolsthorpe’s Quiet Genius

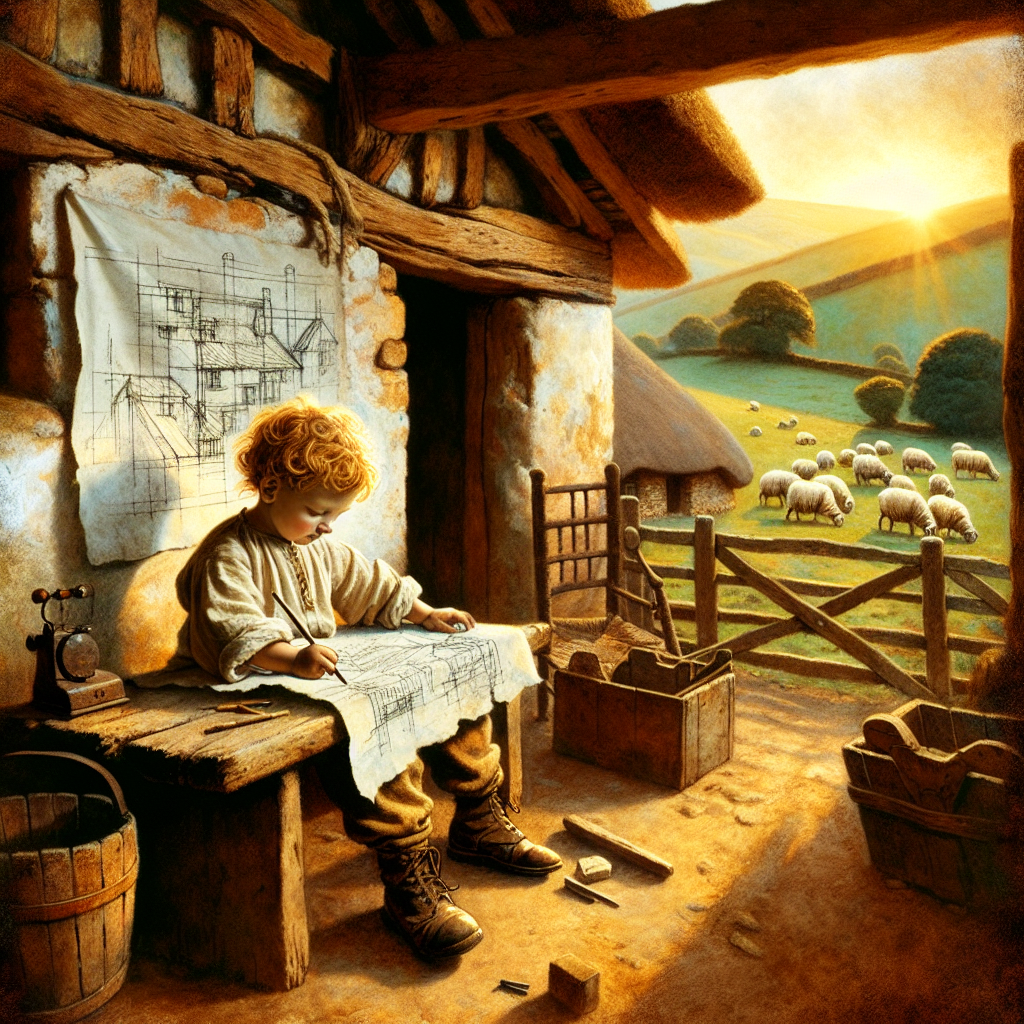

Imagine a calm English countryside where sheep roam and the weather sets the daily rhythm. Isaac Newton spent his childhood here at Woolsthorpe Manor in the 1600s. He arrived early, tiny, and fragile, with his father gone and his mother away, raised mostly by his grandmother.

During the deadly Great Plague of 1665, Cambridge closed its doors, so Newton returned home. Alone and undistracted, he let his thoughts wander. In this short “year of wonders,” he devised new math, explored light and color, and asked why apples fall.

The Apple and the Question

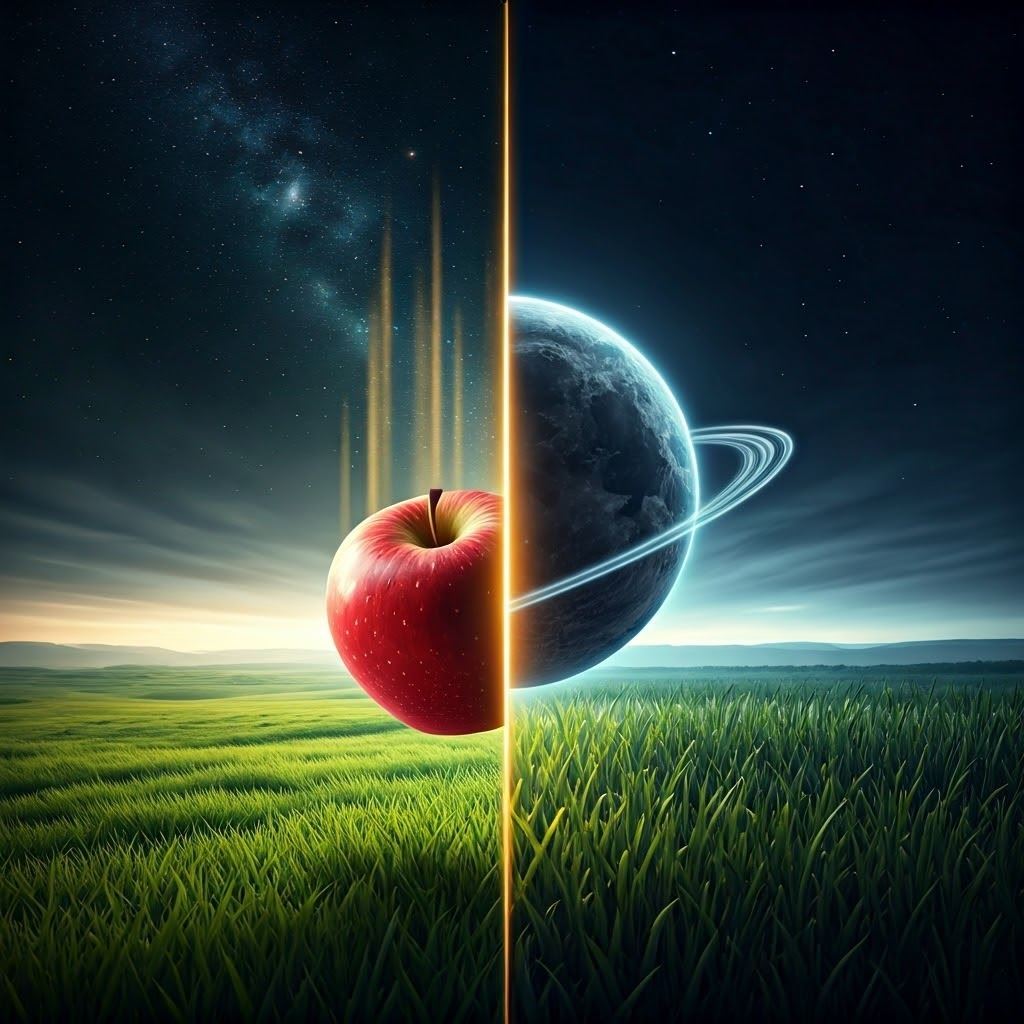

Many know the tale of an apple striking Newton. The event was ordinary, yet the question it sparked was bold. Why does the apple drop straight down instead of sideways or up? Could the same pull that guides the fruit also keep the moon circling Earth?

Newton linked the common and the cosmic. He suggested one simple force rules both apples and planets. In his time, people believed heaven and Earth obeyed separate laws. His insight bridged that divide and hinted at a unified universe.

England’s Scientific Buzz

Seventeenth-century England crackled with new ideas. Coffeehouses welcomed lively debate, and the freshly founded Royal Society offered scientists a place to test and share discoveries. Its journal, Philosophical Transactions, spread news faster than letters alone and encouraged public experiments.

Sharing insights remained hard. Messages crawled along muddy roads, and reputation mattered. Newton, intensely private, hid notebooks in drawers, wrote in Latin, and even coded his findings. His reluctance kept brilliance tucked away.

When he finally revealed his work, he chose careful letters, then landmark books. The Royal Society provided a stage, yet colleagues had to nudge him forward. Thanks to this network, a quiet scholar and a falling apple reshaped how we see a universe ruled by shared laws.