How the Polis Was Born: Geography, Unity, and the First Citizens

Ancient Greece formed its unique polis culture because rugged land split people into small, tight communities. Geography forced them to rely on each other, and that need laid the ground for the first citizen-run cities.

Mountains, Coasts, and the Puzzle of Greek Geography

Greece looks compact on a map, yet its sharp mountains and many islands turned short trips into days of travel. Narrow passes and sheer cliffs hemmed in each valley. Small coves dotted the shore, inviting boats but limiting roads. Isolation bred many independent towns.

Each valley or island ran its own affairs. Think of every Appalachian hollow becoming a self-ruled haven. Over time those pockets traded, quarreled, and copied one another, but distance kept them distinct.

From Villages to Polis: The Art of Coming Together

Tiny farm clusters slowly merged through synoecism, the habit of joining nearby settlements for safety and worship. Families agreed on a defensible hill or a busy harbor, built walls, and shared a new meeting place.

Sometimes persuasion worked; sometimes force. A strong clan, a heroic leader, or a short war could push neighbors together. The result lifted people from village life into a broader civic identity.

A fresh center—part market, part shrine—gave everyone a reason to gather. This shift marked the birth of the city-state.

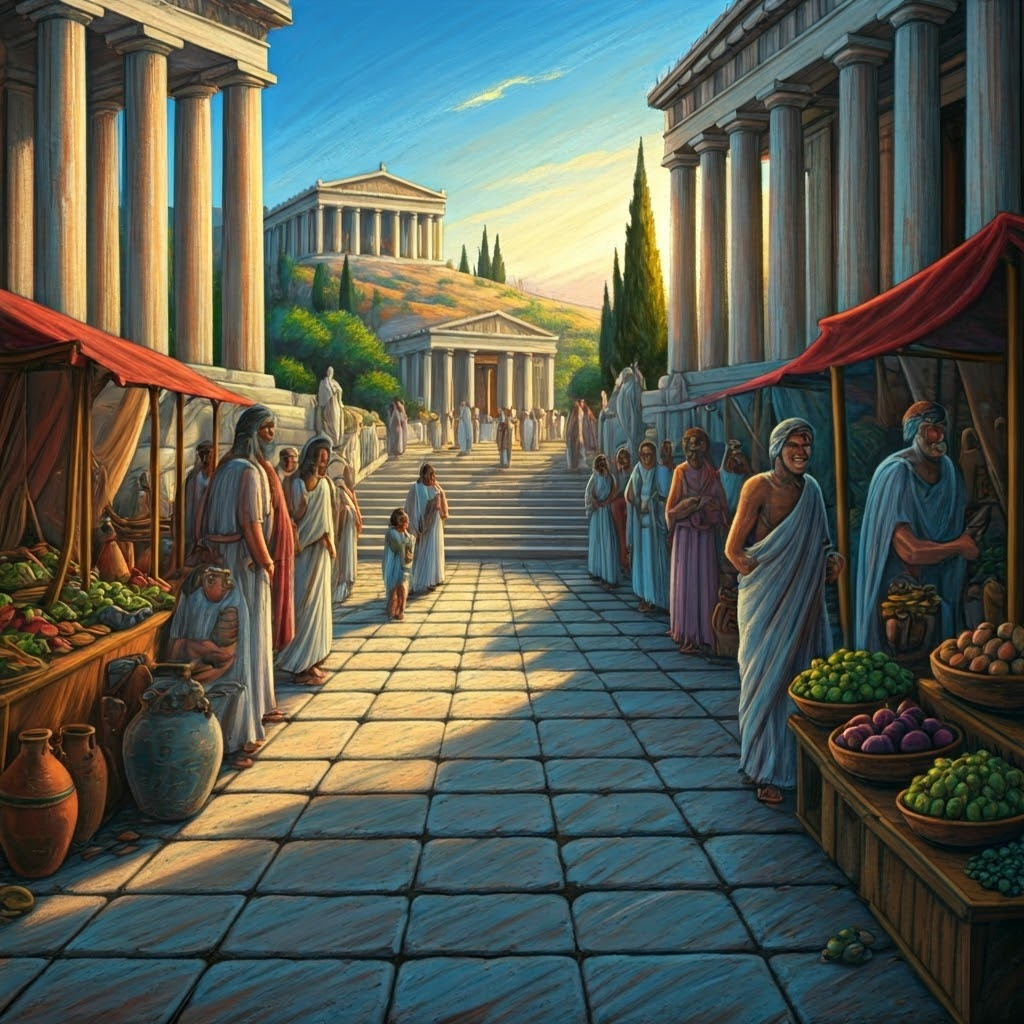

The Agora and the Assembly: Where Citizens Met

The agora was more than a bazaar. Merchants bartered, gossip flowed, and disputes settled under open sky. Temples ringed the square, reminding all of shared faith.

Near the market sat the assembly space—maybe a stepped hillside like Athens’ Pnyx. On meeting days ordinary men voiced opinions, voted on wars, and set taxes. Politics became a public act, loud and visible.

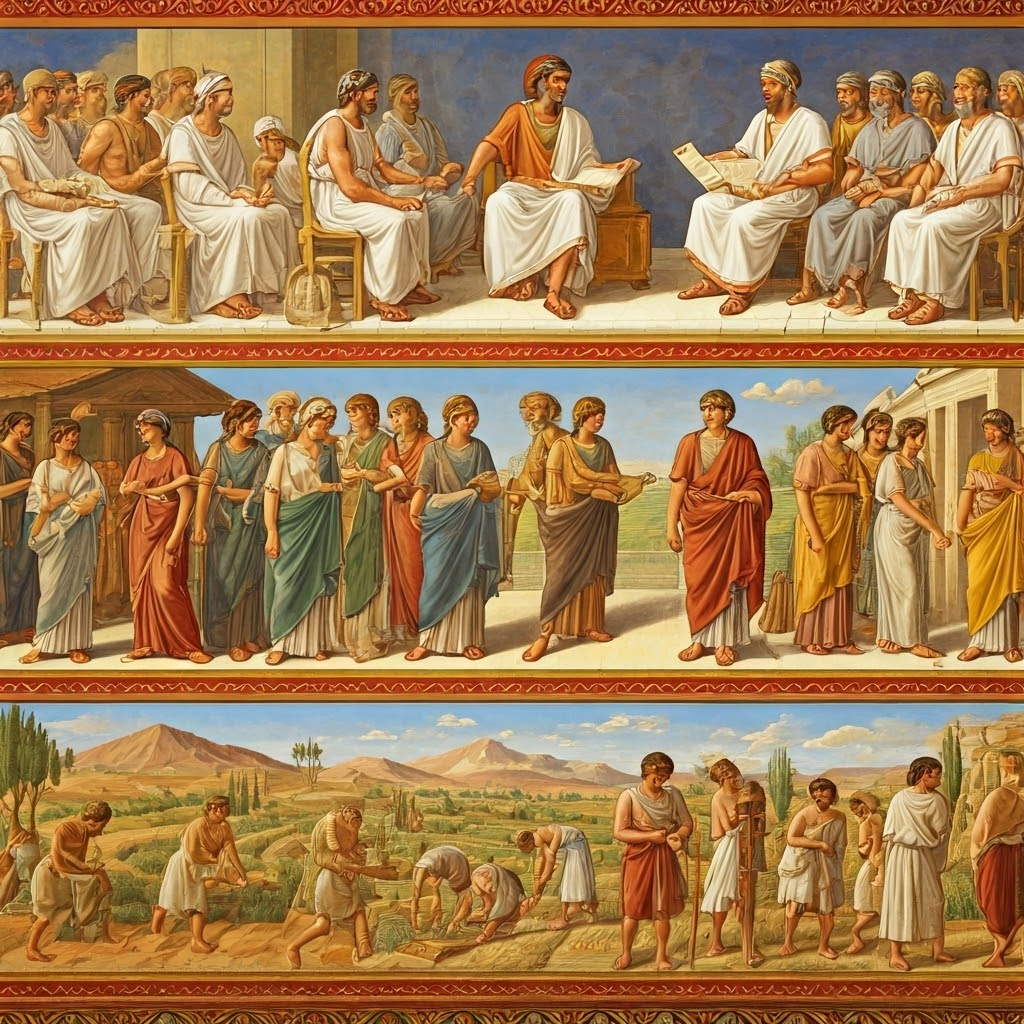

Who Belonged? Citizens, Metics, Women, and Slaves

Full citizens were few. In Athens you needed two citizen parents and adulthood. Sparta demanded even stricter lineage and training. Citizens enjoyed rights but also owed military and civic service.

Metics—resident foreigners—paid extra taxes and lacked political voice, yet fueled trade. Women guided households and rites but stayed outside formal power. Slaves, nearly one-third of Athenians, had no rights at all, no matter their skills.

The Meaning of Belonging

Belonging to a collective mattered more than walls or land. A citizen’s voice shaped laws and wars; outsiders watched from the margin. This new sense of shared responsibility—born in rocky landscapes and noisy squares—still echoes whenever people gather to decide their community’s future.