Finding Your Bearings: The Art of Knowing Where You Are

Space feels strange without gravity. On Earth you look at the Sun or horizon to know which way is down. In a spacecraft there is only darkness, so orientation becomes life-support. Solar panels must face the Sun and antennas must aim at Earth, or the mission fails.

The Spacecraft’s Sense of Direction

Imagine standing in a silent black room and searching for a door. You would notice small drafts or faint sounds. A spacecraft does something similar with sensors such as gyroscopes, inertial measurement units, star trackers, and sun sensors. Each device adds one clear clue to a shared picture of direction.

Gyroscopes and Inertial Measurement Units: The Spinning Truth

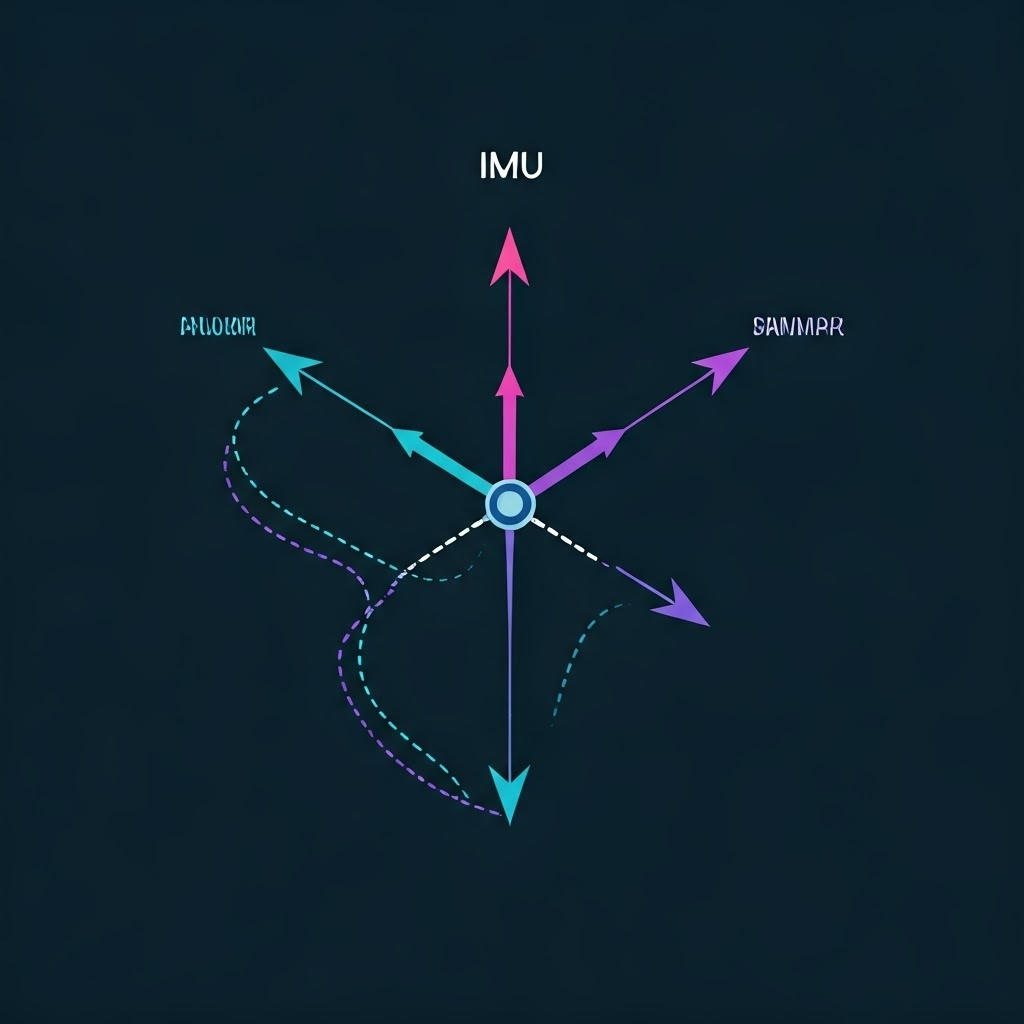

Spin in a swivel chair and you feel resistance. That resistance shows angular-momentum at work. A gyroscope uses the same rule. When the craft turns, the wheel inside fights the change, and sensors read that fight to measure rotation.

One gyroscope measures only turn rate, not absolute direction. Combine several into an inertial measurement unit (IMU) and you trace every twist—like remembering each step in a dark maze. The IMU updates orientation many times per second, giving rapid yet still partial confidence.

Even top-tier IMUs slowly drift. Tiny errors pile up and the internal map slips. Apollo crews stopped that drift by pausing and realigning with stars. Modern craft still need fresh references, so other sensors join the mix.

Star Trackers and Sun Sensors: Reading the Sky

Stars keep fixed positions for navigation. A star tracker is a smart camera that snaps the sky, matches patterns, and returns orientation within a fraction of a degree. That accuracy makes stars the gold standard for absolute pointing.

Sun sensors are simpler. They judge the Sun’s direction by how much light each cell receives. This low-cost cue keeps solar panels bright and prevents delicate instruments from staring straight into the Sun.

Hubble blends fast gyros for smooth moves with star trackers for fine aim. Its sun sensors guard the cameras from lethal glare. Every sensor fills a precise, complementary role.

Putting It All Together: Sensor Fusion

Each sensor is strong in one situation and weak in another. To create a single reliable answer, the craft uses sensor-fusion algorithms. The process mixes fast gyroscope data with precise star and Sun fixes, balancing confidence in real time.

A Kalman filter weighs every reading, trusts good inputs, and discounts bad ones. If cosmic rays blind the star tracker, the filter leans on gyros until the camera recovers. This adaptive math keeps the attitude solution steady through surprises.

During Mars landings, IMUs guide the chaotic entry when stars and the Sun vanish. Once descent calms, sky sensors reset orientation and erase accumulated error.

Why Orientation is Mission-Critical

If a craft loses attitude control, it may drain batteries, overheat, miss science targets, or spin apart. Japan’s Hitomi telescope showed how one sensor fault can start a fatal chain. Reliability in attitude control is non-negotiable.

When every system works, a lonely machine holds perfect aim across millions of kilometers. It steers with physics, starlight, and tireless sensors—proof that careful teamwork lets us navigate the vast, silent dark.