From Sketches to Space: How Ideas Become Habitats

The dream of living in space started on paper, not in a NASA lab. Early writers and artists filled notebooks and pulp magazines with visions of spinning stations that could ease crowding on Earth and satisfy our urge to explore.

Dreams on Paper: The First Space Home Ideas

In the 1970s physicist Gerard O’Neill asked, “Is a planet’s surface the best place for a growing high-tech society?” His class sketched a vast spinning cylinder that could mimic gravity and hold cities. NASA studies soon turned such sketches into serious reports.

These early drawings spoke to basic needs—room to grow, endless sunlight, and freedom from gravity. Designers still revisit them for inspiration when planning today’s habitats.

Shapes in the Void: Comparing Space Home Designs

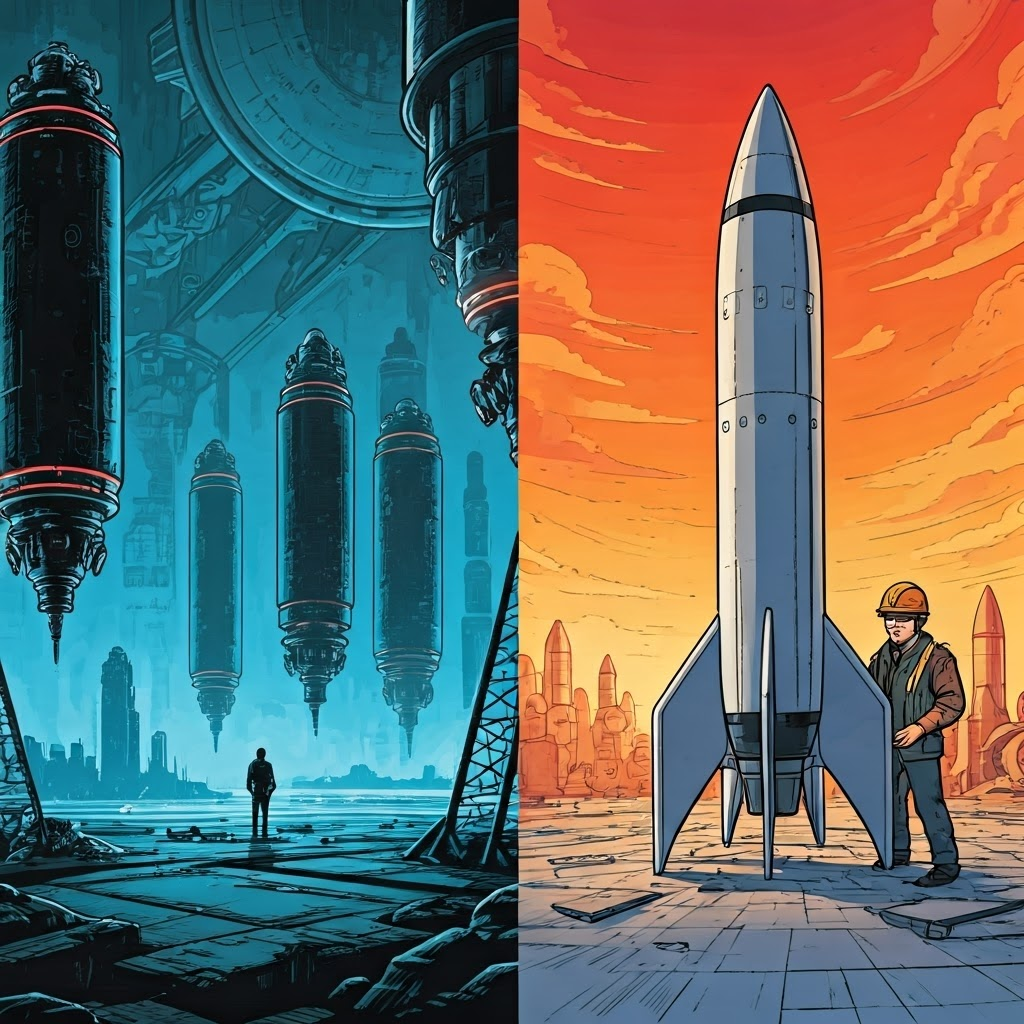

Shape is about more than style—it decides survival. Each famous concept must hold air, block hazards, create gravity, and feel like a neighborhood.

The O’Neill cylinder spins to give gravity along its inner wall. Vast mirrors funnel sunlight inside. Its main hurdle is scale; a city-sized shell is far beyond today’s launch limits.

A Bernal sphere is a giant glass-like globe that also spins. A Stanford torus works like a bicycle wheel—compact and lighter, making it popular for first-generation bases.

Modern engineers test inflatable modules that launch folded and expand in orbit. On the Moon, roomy lava tubes offer natural shielding against radiation and impacts.

On Mars, thick ice domes could freeze in place from local water. They block radiation yet let light feed crops—an elegant, low-mass solution.

One Design, Many Solutions

Every concept is a trade-off—size versus cost, comfort versus safety. Engineers mix features to suit each mission rather than chasing one “perfect” shape.

Turning Ideas Into Blueprints: The First Engineering Steps

Building starts with four challenges: structure, air, gravity, and safety. Strong yet light shells may use steel, titanium, or composites. Inflatables rely on layered fabrics until pressurized. Lunar or Martian bases might 3-D print local soil into walls.

Air must stay sealed at the right mix and pressure. Natural caves or ice domes help because their walls are already almost airtight.

Spinning habitats create artificial gravity through centrifugal force. Spin too fast and crew feel sick, so larger diameters are safer.

Space throws radiation, micrometeoroids, and temperature swings at any shell. Designers add water tanks, soil, or thick metal to absorb those threats.

Real Engineering: From NASA Sketch to ESA Studies

NASA’s 1975 Summer Study turned dreams into line-item budgets. ESA builds on that legacy with plans that use local materials and robotic assembly. Today, every station idea still follows the same path—sketch, trade-offs, study, and safety review.

Fiction invents force fields. Engineers juggle mass limits, rocket sizes, and human psychology. Yet bold sketches keep sparking real solutions—proving that we must start with imagination and finish with math.