Baghdad’s Spark: Where Curiosity Became Power

The House of Wisdom: A Meeting Place for Minds

Picture Baghdad a millennium ago. Broad avenues echoed with poetry, bright markets buzzed, and at their heart stood the House of Wisdom—a place built for minds that never stopped asking questions.

It worked like a research hub. Scholars from Greece, Persia, India, and Arabia gathered to read, debate, and translate. Their shared goal was knowledge, not rivalry.

Translation meant more than swapping words. Teams mixed Greek science, Persian math, and Indian astronomy into clear Arabic prose. This cross-pollination sparked fresh ideas and a new intellectual language.

You might see a Persian Jew, a Nestorian Christian, and a Muslim scribe leaning over parchment. Their collaboration mattered more than creed—and caliphs paid handsomely for results.

When they uncovered a lost work of Euclid or coined a new Arabic term, excitement rippled through the city. Baghdad turned curiosity into celebrity, and its ideas soon flowed far beyond its walls.

Algebra and the Language of Numbers

Inside, you could meet al-Khwarizmi drafting methods that gave us both “algorithm” and algebra. He replaced ad-hoc counting with clear steps to solve unknowns.

His book simplified riddles like so merchants, architects, and judges could calculate with confidence. Translations carried his algebra to Europe, making equation-solving routine for students even today.

Light, Vision, and Ibn al-Haytham’s Experiments

Elsewhere, Ibn al-Haytham questioned how we see. He argued that light enters the eye instead of leaving it—a bold reversal of ancient belief.

To prove it, he built a camera obscura. The upside-down garden image on the wall showed how rays travel in straight lines. His experiments placed evidence, not authority, at the center of science.

Europe later adopted both his questions and his methods, laying groundwork for the modern scientific approach—ask, test, repeat.

Paper: The Quiet Revolution

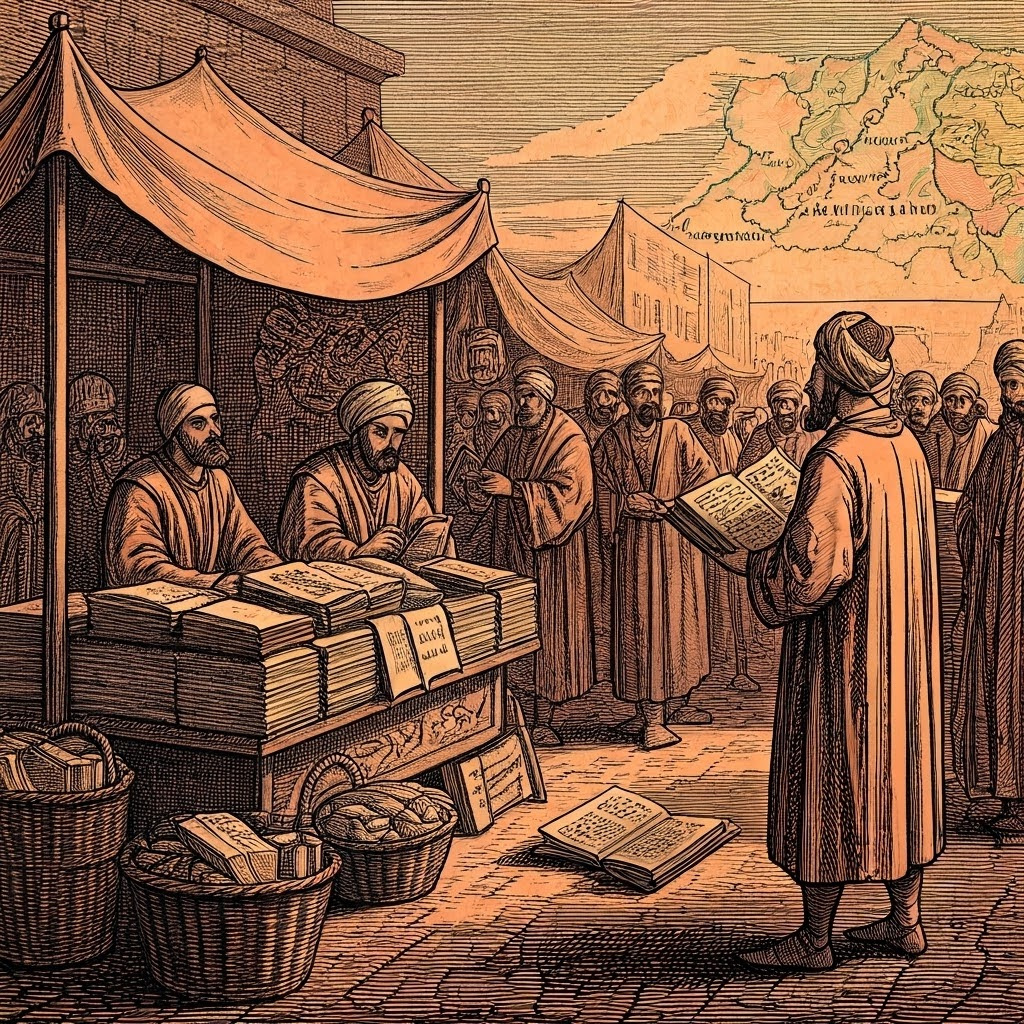

Knowledge needed a carrier. After 751, artisans learned Chinese techniques and made paper from linen rags in Samarkand and Baghdad. It was lighter, cheaper, and easier to copy than parchment.

Affordable sheets let scribes multiply books quickly. Markets overflowed with texts, turning paper into the medieval world’s communication network. From Baghdad, papermaking spread to Damascus, Cairo, Sicily, Spain, and finally Europe, where universities thrived on the new material.

Connecting the Dots

Across algebra, optics, and paper runs one bright thread—curiosity joined with open collaboration. These sparks from Baghdad crossed borders and centuries, reshaping how people learn, trade, and understand the world. Think of them as an invisible bridge of light, carried forward by every eager mind that followed.