Power in Unexpected Places: Queens, Leaders, and Lawmakers

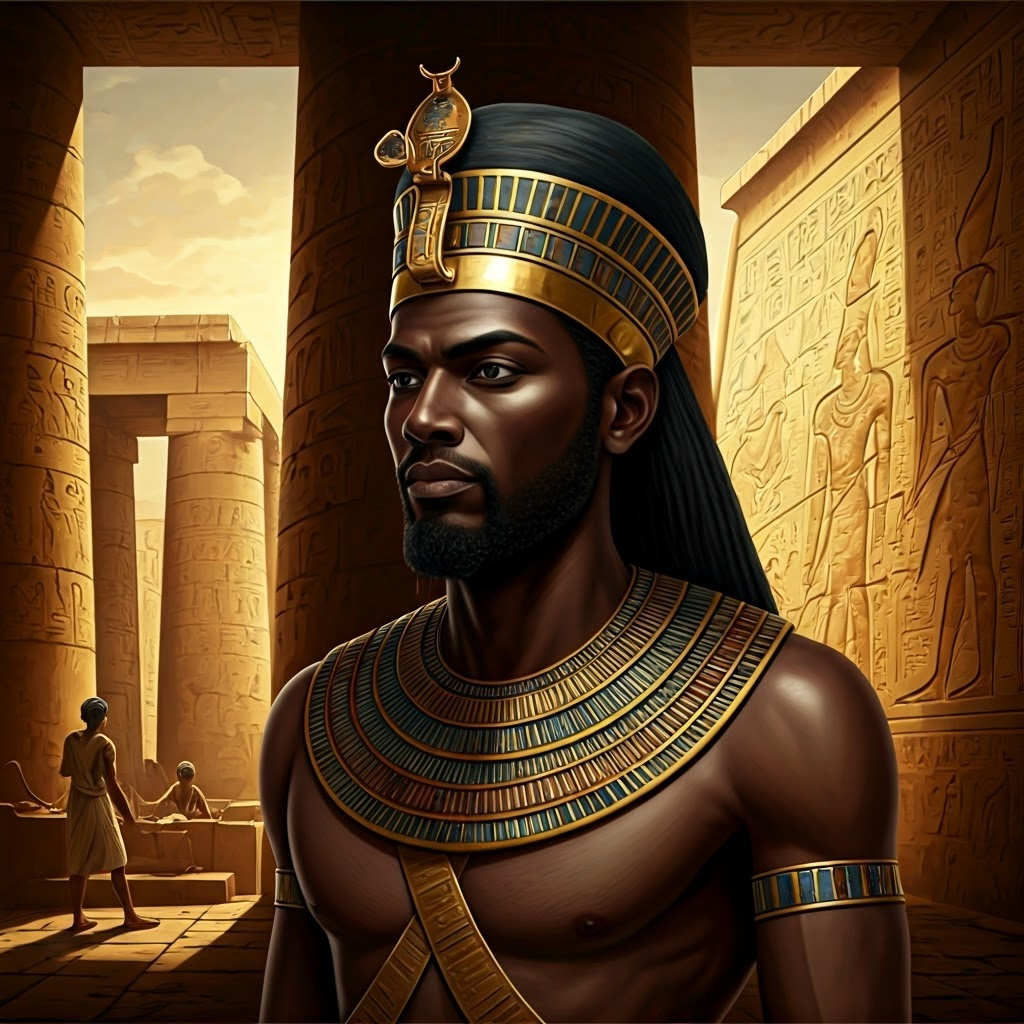

Mothers of Invention: Matrilineal Societies and Early Power

Some ancient communities traced family, property, and status through the mother’s line. Children belonged to her clan, and power often moved from mother to daughter. This system gave women visibility long before most written records began.

Anthropologists note that in pre-dynastic Egypt and parts of West Africa, inheritance followed the maternal side. A king’s claim could rest on his mother’s blood, not his father’s, weaving legitimacy directly through her name.

Matrilineality did not erase patriarchy, yet it opened space for women to become brokers of land, titles, and alliances. Even after male-centered rule took hold, echoes of the older respect lingered in language and legend.

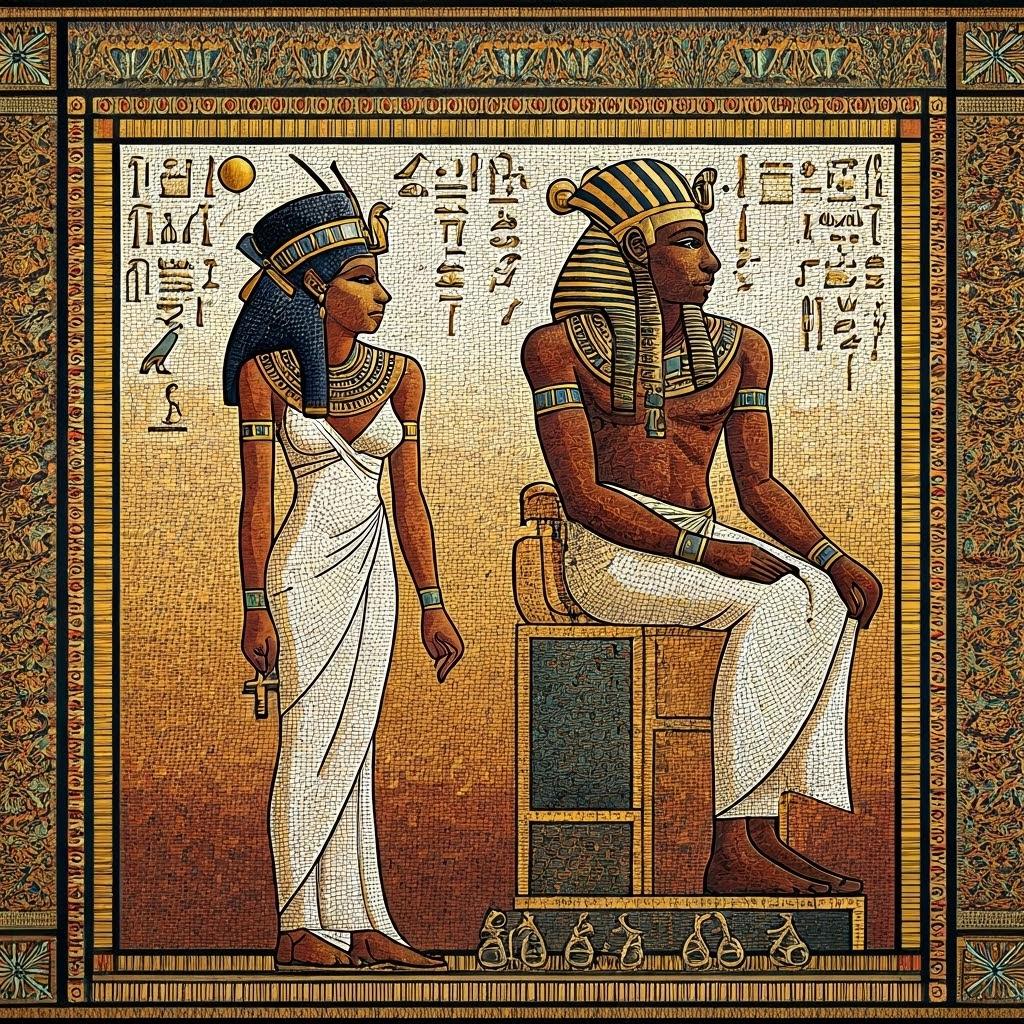

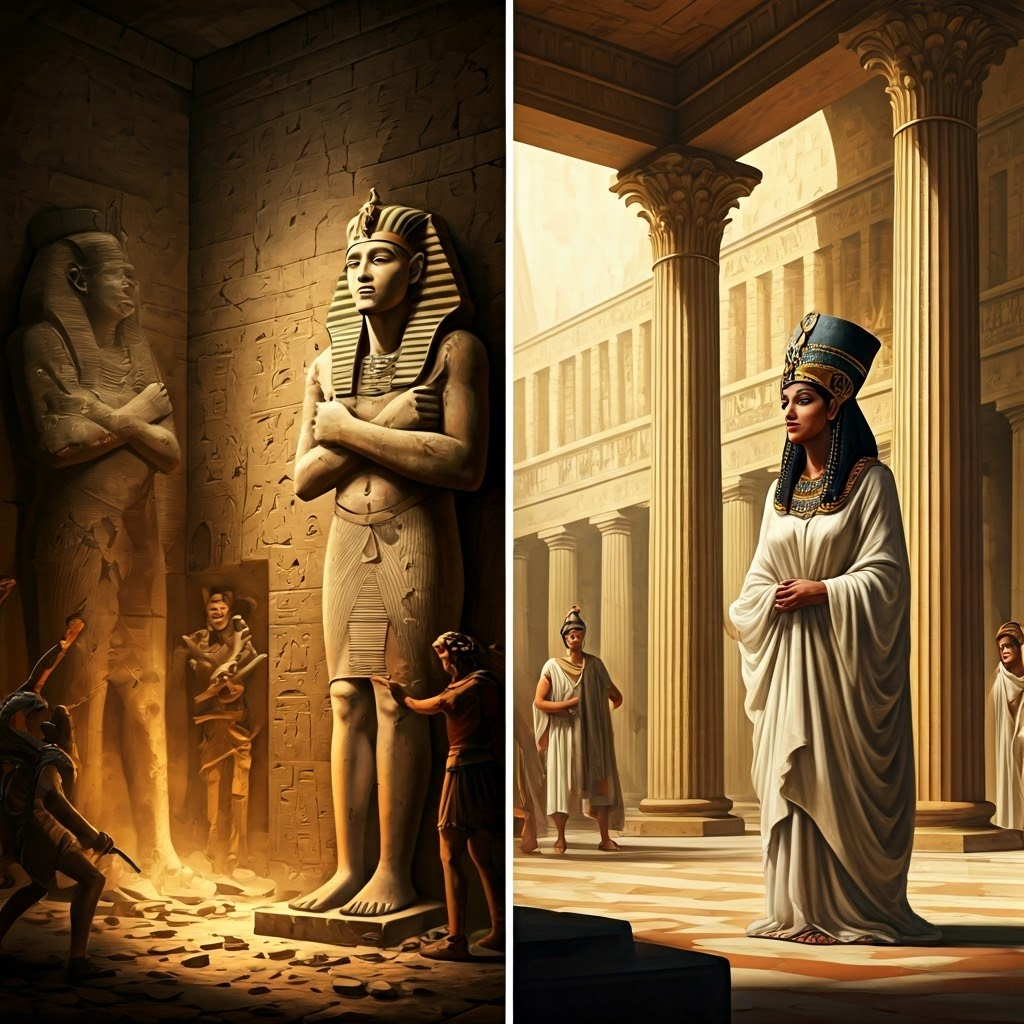

Pharaohs in Skirts: Hatshepsut and the Egyptian Queens

Walk into an Egyptian temple and you might see a ruler in the nemes headdress and royal beard—yet the face is female. Hatshepsut claimed full pharaonic power around 1478 BCE. She wore male regalia, used kingly titles, and spoke of divine birth to secure authority.

Her works include the terraced temple at Deir el-Bahri and lucrative trade expeditions. After her death, erasures meant to hide her reign instead guided modern archaeologists to her story.

Other queens—such as Cleopatra VII—also steered policy, forged alliances, and led armies. Their crowns, cobras, and inscriptions signaled power the public understood.

Sea Wolves and City Walls: Artemisia I and Women at War

Artemisia I of Caria ruled a Greek city yet sailed with Persia at Salamis in 480 BCE. Her daring tactics impressed even Herodotus, who quoted Xerxes saying his men had become women, and his women—warriors.

Legends tell of Queen Tomyris defeating Cyrus the Great and Carthaginian women turning hair into bowstrings. Such stories prove courage crossed gender lines whenever survival demanded it.

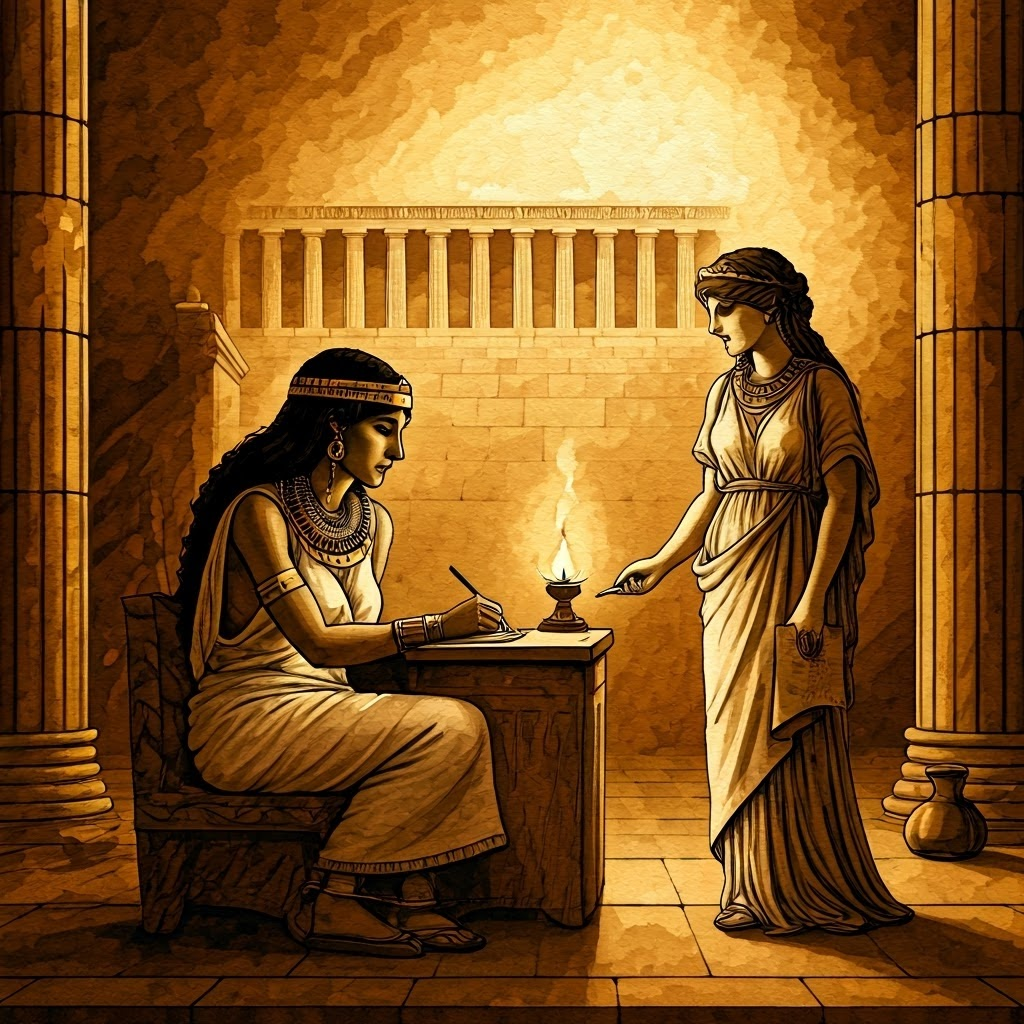

Laws, Loopholes, and Limits: Women’s Legal Status in Ancient Worlds

Early law codes, like Hammurabi’s, tilted toward men. Women faced strict rules on property and marriage. Even so, religious offices in Sumer let certain women own land, lend money, and file suits—small but vital loopholes.

Clay tablets from Nippur record priestesses making contracts, while Athenian heiresses used guardians to manage estates. Legal cracks offered room for skillful negotiation.

Why Their Stories Matter

Ancient women shaped dynasties, laws, and wars, even when records downplayed them. Their footprints remind us that agency often survives in unexpected forms, widening our view of past and present possibilities.