Picking Up the Pieces: People, Places, and Pain

A World on the Move: Refugees and Displaced Lives

When the fighting stopped in 1945, Europe and Asia saw the largest displacement in history. Cities such as Warsaw and Berlin lay in ruins. Borders shifted overnight, and ordinary families now wandered in search of safety and purpose.

More than 60 million people were suddenly without homes. They included forced laborers, camp survivors, freed prisoners, and civilians fleeing violence. Authorities called them Displaced Persons or DPs. Many, like Janina from Poland, found freedom but not home—parents missing, villages gone, roads crowded with others just as lost.

Governments and aid groups raced to help. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration—UNRRA—set up camps that offered powdered eggs, bread, and watery soup. Children made rag-ball soccer games while adults scanned bulletin boards for familiar names. For Holocaust survivors and others who could not return, these camps became waystations to new lives in the United States, Australia, or Israel.

Justice on Trial: Nuremberg, Tokyo, and the Search for Accountability

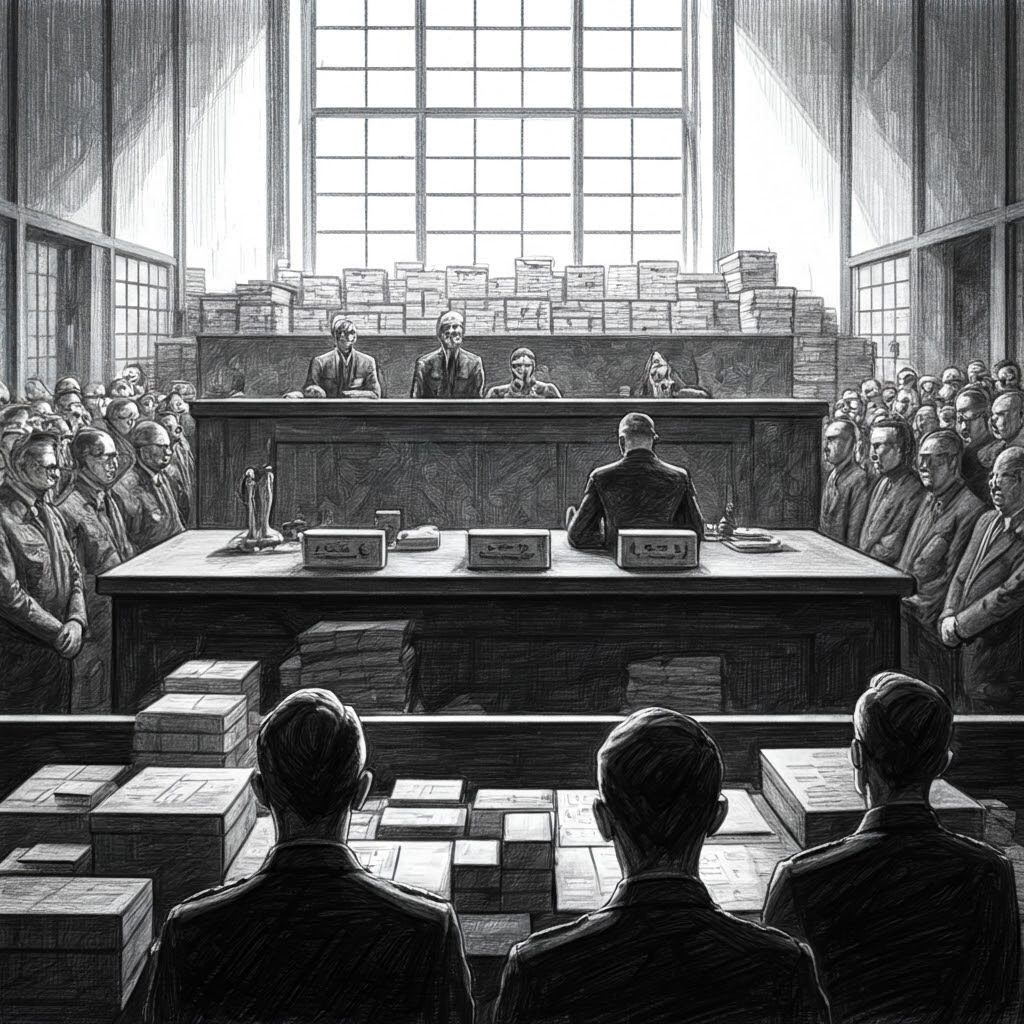

The world sought justice through the Nuremberg Trials in Germany and later in Tokyo. For the first time, leaders—not just soldiers—answered for war crimes before an international court.

At Nuremberg, prosecutors defined mass murder and aggressive war as global crimes. Survivor testimony revealed factory-like killing. Twelve of twenty-four top Nazis received death sentences, yet the larger legacy was a legal framework for crimes against humanity that later guided courts in Rwanda and Yugoslavia.

The Tokyo Trials followed, charging Japan’s wartime leaders for atrocities such as the Nanjing Massacre. Critics noted uneven justice—Emperor Hirohito was never tried—but the process still reinforced global responsibility for leaders who wage brutal wars.

Coming Home: Demobilization and the Veteran Experience

Turning armies back into civilians—demobilization—was massive. The United States processed eight million service members. Britain issued “demob suits,” ration cards, and rail tickets. Clothing, however, could not mend shattered identities.

Many veterans carried invisible wounds: nightmares, anxiety, a constant sense of danger. The term PTSD did not yet exist, so society urged them to “move on,” even when they struggled to sleep or speak of their past.

Policies differed sharply. The U.S. GI Bill funded college and home loans, fueling suburban growth. Soviet authorities often distrusted returning POWs, sending some to labor camps. In Germany and Japan, ex-soldiers faced devastation and public shame.

Communities Rebuilding: Beyond the Ruins

Across Europe, neighbors joined in rebuilding. In Rotterdam, volunteers lined up bricks from rubble to repair schools and churches. Aid from the Red Cross and Save the Children brought food, clothing, and medical care, but hope traveled mainly through shared labor and music in shattered halls.

Trust had frayed—some neighbors had collaborated or betrayed under occupation. Communities wrestled with forgiveness and accountability, forming new local councils and welfare programs. Small acts—sharing bread, teaching children—stitched society back together.

Daily life still held grief, yet laughter and love re-emerged. Those modest joys signaled ongoing renewal, proving that even after immense catastrophe, people can start again.